Secular content appeared in the folk print only in the first quarter of the eighteenth century. These worldly themes were a response to the secularizing policies of Peter the Great and to his program of reforms that affected all aspects of Russian life, turning the patriarchal and backward Russia into a modern and westernized empire. Of course, the forcible europeanization and secularization of the country found many opponents, especially among the streltsy, the Old Believers, and the conservative members of the upper classes. The satirical prints seem to reflect popular anti-Petrine feelings. Most traditionalists found the tsar's reforms controversial and difficult to accept. One of the best known lubki directed against Peter's policies is The Barber Wants to Cut Off an Old Believer's Beard, a protest against the forcible shaving of beards and mustaches.

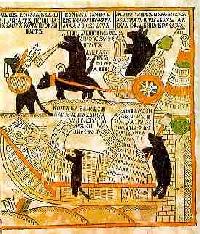

Yaga Baba Rides Off to Fight the Crocodile, can be interpreted as an Old-Believer satire on Peter and his wife Catherine, since the adherents of the "old faith" called Peter "the Crocodile," and the figure of Yaga Baba (a reversed name of the witch in Russian fairy tales, Baba Yaga), shown in the print wearing the traditional Estonian costume, is a mockery of Catherine, a native of Estonia. As if to avoid any possible misinterpretation of the woodcut's subjects, the author placed a little picture of a ship in the left bottom corner, hinting at Peter's love for ships and his creation of the Russian navy.

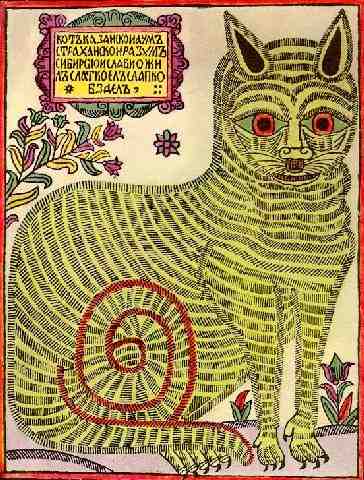

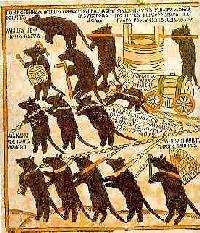

The Cat of Kazan seems to satirize Peter's titles, his mustache, and his lifestyle, while How the Mice Buried the Cat, one of the perennial favorites of the lubok buyers, apparently includes a number of important elements which identify the cat as Peter the Great and the mice as the Russian people. The print shows two of the mice playing musical instruments. Music was allowed by the tsar for the first time only in 1698, during the funeral of his friend Lefort. The orchestra was also present during Peter's burial, and his funeral sled was drawn by eight horses. One of the mice is smoking a pipe, an allusion to the tsar-reformer's introduction of tobacco sales. In the upper right corner, two mice are riding in a one-axle cabriolet or gig, forbidden by Peter's father Alexis Mikhailovich, but allowed during Peter's reign; in fact, it was one of the tsar's favorite means of transportation. Other versions of the print include even more anti-Petrine allusions (cf. Sytova, ill. 92).

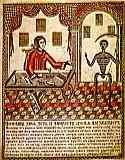

The tsar, his wife, and his reforms were not the only objects of the lubok's satire. The prints soon started poking fun at societal vices and mores. Pan Tryk and Khersonia criticized loose morals and frivolity of the nobility. The Male Cock-Rider and The Female Hen-Rider, adaptations of German and French pictures, ridiculed maritial infidelity and cuckolded husbands. The Judgement of Shemiaka and The Tale of Ruff Ruffson, based on the popular seventeenth century democratic tales with the same title, satirized the court system and corrupt judges. The Glorious Gobbler and Merry Bibbler, a reworking of the French illustration to Gargantua's feast, laughed at intemperate eating and drinking.  The Dutch Quack Doctor and Pharmacy Proctor chided old ladies who believed that a miracle-machine of a quack could make them look and feel younger. The Money Devil criticized avarice, and The Proverb: Even Though the Snake Is Dying, Still to Grab the Grass It's Trying, with the text written by the poet and dramatist Alexander Sumarokov, was directed against bribe-taking. It depicted a clerk who became so accustomed to asking for and taking bribes that he even tried to get money from Death when it came for him. This Rule Since My Youth I've Been Promoting, another one of many prints which warned against the demoralizing power of money, depicted a young woman willing to make love to a bull, as long as she were paid for it.

The Dutch Quack Doctor and Pharmacy Proctor chided old ladies who believed that a miracle-machine of a quack could make them look and feel younger. The Money Devil criticized avarice, and The Proverb: Even Though the Snake Is Dying, Still to Grab the Grass It's Trying, with the text written by the poet and dramatist Alexander Sumarokov, was directed against bribe-taking. It depicted a clerk who became so accustomed to asking for and taking bribes that he even tried to get money from Death when it came for him. This Rule Since My Youth I've Been Promoting, another one of many prints which warned against the demoralizing power of money, depicted a young woman willing to make love to a bull, as long as she were paid for it.

The popular I Am the Hop High Head, Greater Than All the Fruit of the Earth, was a stern warning against drunkenness.

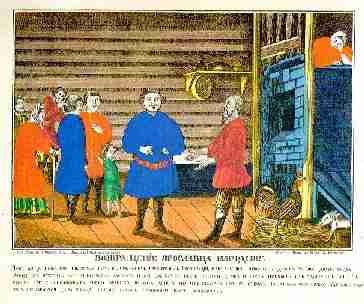

The Return of a Man from Yaroslav Home presented a didactic and funny anecdote about a young man sent from a provincial town to the capital to find a job and to help his family by sending money home. Summoned back by his father, he claims that his job in a restaurant barely allows him to survive. The humor of the print lies in the figure of the young man, who is fat and round and who talks about his "difficulties" while "rubbing his belly."

The Moneylender's Pleasant Dream shows a company of devils helping the moneylender count his profits and stash the money neatly in sacks while The Wedding of the Bear Mishka the Clubfooted is a mild parody on merchant or petty clerk weddings, arranged to impress the invited guests.

The biting satire of the prints inevitably drew the ire of the authorities. As early as 1721, a decree of the Petrine government ordered that all the production and selling of prints had to be approved by the Holy Synod. A year later the government began to censor the religious prints and in 1723 the prints depicting the members of the ruling family. In 1731, the decree which prohibited buying or selling "poorly made" pictures, attempted to restrict the prints by addressing the question of their quality. The measure was repeated, with additional restrictions imposed on the imperial portraits and images of saints, in 1744, 1747, and 1760. The next year, all the "poorly made" boards and prints of saints were confiscated. Catherine II required that all the prints be approved by the Bureau of Decency (police headquarters); no wonder that even at the time of social strife and peasant unrest the pictures showed scenes galantes, flirting couples, beauty mark registers, and advertisements. In 1839, during the oppressive rule of Nicholas I, an official decree subjected all the prints to censorship; the signature of the censor became an obligatory part of each picture. The most damaging action against the lubok was the 1851 decree to gather and destroy all the old uncensored plates. The rich heritage of Russian folk print practically ceased to exist and the new pictures, requiring the official sign of approval, could not even come close to the older ones in the intensity of their criticism and the sting of their satire.