The eighteenth century in Europe is often called a time of Enlightenment. The ideas of the Enlightenment prepared the way for the rapid "progress" of the following century. In the various branches of the arts, new ideas were developing, interacting with each other, and shaping the culture and artistic heritage of Europe. It was at this time, and particularly during the reign of Peter the Great that Russia began to participate in the secular artistic world of the West. Having a different artistic past than Europe and traditionally valuing a different approach to art, the Russian artists needed a period of adjustment to become acclimated to Enlightenment styles and techniques. A short description of the important movements of the time, particularly of Neoclassicism, will provide an insight into the background against which eighteenth-century Russian art should be seen.

Although the eighteenth century encompasses various conflicting styles, neoclassical ideas can be best seen in the genres of historical painting, portraiture, and landscape. In part a reaction against baroque and rococo excesses, neoclassicm is associated, in France, with a return to "virtue" and an acceptance of the new ideological demands of the French Revolution. As a supporter of the revolution, and one of the most important neoclassical artists of France, Jacques Louis David linked neoclassical art with the ideas of duty, honor, and patriotism in such works as Oath of the Horatii and The Death of Socrates. The contemporary literary desire for classical form and structure, exemplified by Boileau's Ars Poetica, together with a renewed interest in ancient Rome (spurred on by new archeological discoveries and a publication of Winkelmann's Antiquities of Rome), furthered the influence and impact of neoclassicism.

By using classical examples as models and guides, neoclassical art is characterized by its sense of order, logic, clarity, and to an extent, realism. Duty to a higher cause, such as one's country or its ruler, as well as the sense of decorum and appropriateness are emphasized. These qualities are seen in the increased "naturalism" of landscapes (such as those of Canaletto and Bellotto) and in the fact that classical models inspired the new changes in landscape painting. In portraiture, artists such as Sir Joshua Reynolds attempted to elevate the genre by infusing it with the heroic influences of the "Grand Style." By incorporating the depth of the historical paintings into portraiture, artists sought to make portraits more than simply representations of "likenesses."

In this time of new ideas and social change, symbolism in painting (especially in portraits) became an important means of defining oneself and one's place in a society. During the reigns of Peter the Great,

Anne, Elizabeth, and Catherine the Great, love and appreciation of Western art was cultivated and encouraged. Just as the Academies of Art had played an important role in the development and legitimization of styles in France and England (by recognizing artists and supporting certain stylistic trends), the Academy of Fine Arts in Russia took on a similar centralizing role. By sending talented students to study in Europe, employing foreign artists and importing the works of European masters, the Russian rulers were able to insure the penetration of Western aesthetic ideals into the fabric of Russian artistic life. Although some artists simply imitated the Western masters (as did many less original Western artists), artistic representation that transcends simple imitation can be found in the works of Dmitrii Grigorevich Levitskii, Vladimir Lukich Borovikovskii, Ivan Petrovich Argunov, Aleksei Petrovich Antropov, Fedor Stepanovich Rokotov, Ivan Firsov, Ivan Nikitin, Andrei Matveev and others. [B.B.] The three portraits reproduced here give a good idea of the tremendous technical and stylistic advances made by Russian painters within half a century. None of the portraits shows any traces of "backwardness," provincialism or amateurism. Argunov's portrait of the Count Petr Borisovich Sheremetev

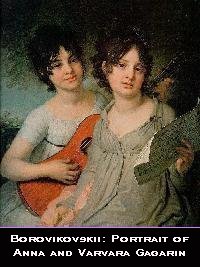

proves that the painter has moved from the early parsuna-like timid attempts at portraiture to a mature and confident Western style. The modeling of the Count's face is competent and expressive, while Argunov's fondness for detailed rendering of his sujects' clothing and for warm colors does not violate the unity of the composition. Borovikovskii's portrait of the sisters Gagarin, painted in 1802, with its clear design, its linear character, its simplicity and overall "good taste," is a good example of the painter's absorbtion of neoclassical ideals. The portrait of Ekaterina Ivanovna Nelidova is one of the famous paintings commissioned from Levitskii by Catherine the Great to commemorate the performances of the students of the Smolny Institute. Besides depicting with great skill the soft and shiny fabric of the girl's dress and showing his mastery of color by contrasting glowing pink and rose tones with grey, blue, and pale green, Levitskii also proves to be a good observer of human character. Since Nelidova is on stage, playing the role of the servant Serbina in Pergolesi's opera La Serva Padrona, the artist shows a certain artificiality and awkwardness in the model's pose. However, the girl's lips and eyes are smiling -- she seems to be having such a good time that even the presence of the Empress at the performance cannot hamper the fun. [A.B.]