The nineteenth century in Russian art was a time of great changes and developments that led to the establishment of a truly Russian school of art. The eighteenth-century dependence on European art and styles gave way to a reaffirmation of Russian heritage and to new interpretative approaches, different from Western standards. Nevertheless, as a result of the acceptance of Western art techniques and styles during the preceding era, Russian art would be connected to, and perhaps interpreted by, European standards and ideals. The historical and cultural development of Russia in the nineteenth century finds its expression in numerous artistic movements which can be divided into three main trends:

Romanticism,

Ideological realism,

Russian (Slavic) revival.

Early in the century, Russia's artistic community continued to share much in common with contemporary European art. Focus was placed on the schools of Rome, Bologna, and Paris and the Russian artists were skilled in the techniques and stylistic approaches popular in Europe. With the advent of Romanticism, a new emphasis was placed on the portraits of individuals (in particular, portraits and self-portraits of artists) and representations of historical events. Moreover, as art began to spread beyond the court circles, Russian artists took renewed interest in the world surrounding them instead of admiring distant European countries. This change was reflected in a move towards greater naturalism. However, throughout the early part of the century, the conflict between classicism, idealism, and naturalism was clearly visible, and it was only toward the middle of the century that the realistic tendencies became dominant.

|

(Picture courtesy of Hillwood Museum) |

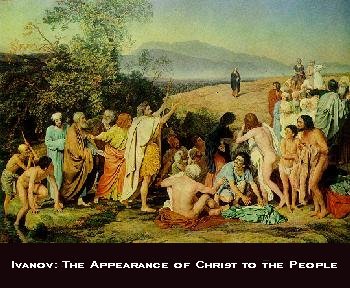

In the gradual development of a Russian ideal and cohesive style, Karl Briullov occupies an important place. A particularly versatile painter, he achieved international fame with his historical epic canvas The Last Day of Pompeii. Through this succes he showed how completely the Russian artists have mastered the Western artistic idiom and technical advancements. Furthermore, he advocated a loosening of the formal neoclassical restricitions adopted by the Russian art comunity from the West, leading the way to the freer approach to art that would become so important to the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers, Itinerants). As this trend continued, naturalistic and more nationalistic tendencies began to replace the Western European style. Younger generations of artists started learning from their compatriots. For instance, I. A. Ivanov's religious paintings, particularly his monumental The Appearance of Christ to the People (1837-57), gave impetus to the Slavophiles' interest in Byzantine and Medieval Russian art.

With the rise in national spirit, genre painting, which had always been considered a rather inferior branch of the arts, gained strength and established itself as a valuable part of the Russian artistic heritage. The new interest in peasant life, culture, and traditional costumes can be seen in the works of Aleksei Venetsianov. His realistic portrayal of the Russian peasant and his poetic attitude towards the Russian landscape are important starting points of this tradition. Other painters, particularly Fedotov, examined the middle class and in their works gave first examples of social criticism, a trend which would increase in the second half of the nineteenth century. Taken together, the art of this early period, including the portraiture, conversation pieces, genre painting, and historical canvasses, became known as romantic realism. It was characterized not only by a growth of naturalism, but also by focusing attention on the individual, and by an increased appreciation for the Russian landscape, for the life of the Russian peasant, and for the medieval heritage of Russia.

The next significant movement of the nineteenth century is known as ideological realism. After the emancipation of the serfs and the new "liberal" atmosphere ushered in by the reforms of Alexander II, the artists of the period felt the need to go beyond art's aesthetic functions and to play a role in the moral and social education of the population at large. No longer was art supposed to be for the wealthy alone; it should be available to all. Implied by the new ideology was an assumption that art should function as an instrument of social criticism. Russia and its people became the new focus of attention. This new attitude could be seen particularly well in the works of Perov, whose realistic style heightened the focus of his criticism. Although this new movement was profoundly affecting the subject matter, no parallel change in painting technique occured at the time.

Considering the nature of the ideas that were espoused by the Russian artists of this period and keeping in mind the traditionally conservative attitude of the "paragon of style and taste," that is, the Academy of Arts, it almost seems fitting that in 1863 thirteen artists, led by Ivan Kramskoi, resigned from the Academy in order to pursue independently their artistic visions. All students at the Academy participated in the annual Gold Medal competition. When the topic of the 1863 competition, "Odin's Feast in Valhalla," was announced, Kramskoi and his followers decided to

forfeit their chances of winning a stipend and a trip to Europe, believing that such a mythological fantasy was too remote from the real life of Russia to deserve their attention. They wanted to have the right to choose their own subjects without having to conform to the outdated and artificial categories proposed by the Academy. Known as the Peredvizhniki (Travelers, Wanderers, Itinerants) because several years later they formed the Society of Traveling Exhibitions, the rebels and their followers were able to reach a larger group of viewers than they could have had in the Academy. Ideological realism, which embodied a new degree of realism and national spirit, developed fully outside of the confines of the Academy.

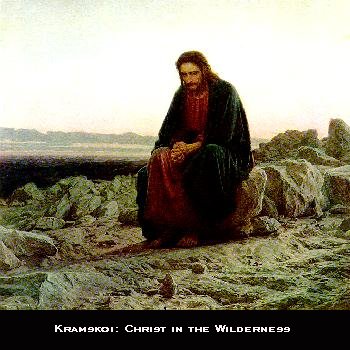

Ivan Kramskoi and Nikolai Ge (Gay, Ghe) played important roles in the development of the religious painting. Kramskoi's Christ in the Wilderness (1871) combines an almost photographic vision with a haunting mysticism. At a time when new ideas seemed to contradict traditional beliefs, this painting became an important marker in Russian religious painting. Similarly, Ge's new naturalistic approach combines for the first time with a new technical approach to complement his new style. As ideological realism developed, the social criticism merged with the genre of historical painting. This trend is seen particularly well in the works of Surikov; his stylistic approach and his subjects contributed to the renewed interest in Russia's past. However, one of the best examples of ideological realism in Russian art is Repin's acclaimed They Did Not Expect Him. Its subject is taken from contemporary Russian life rather than from Russian history. By combining social criticism with realistic presentation, Repin created a model work of the late nineteenth-century realism. The late nineteenth century was the time of the Slavic (or Russian) Revival, a movement which grew out of the conflict between those who believed that Russia should define itself in Western terms (with an increasing incorporation of Western ideas and ideals) and those who thought that a return to and rediscovery of Russian heritage was best for the nation. This movement can be seen even as a rejection of the policies and ideas of Peter the Great, with his emphasis on secularization and westernization, and as an affirmation of national heritage. An important part of Russia's artistic development, the Slavic Revival focused on the medieval art and architecture of Russia and the richness of the Russian culture as found in the lives of Russian peasants. Obviously, the earlier movements

of the century as well as political and social developments and recent archeological discoveries helped prepare the way for the revival.

The Slavic Revival began by turning away from the West toward the rich past of Muscovy. Later, it developed into Pan-Slavism which included Kievan Russia as part of Russian cultural heritage. The movement led to an overall attempt to recapture the richness of Medieval Russian art, architecture, culture,

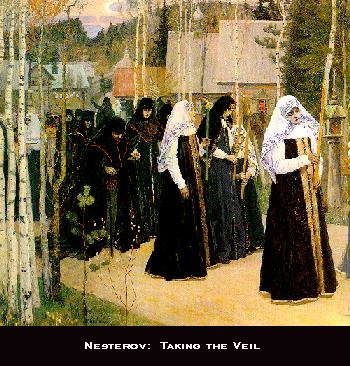

and Orthodox Church, as well as the heroic nature of Kievan history, as seen in the works of Viktor Vasnetsov. Influenced by folk tales, heroic epic and extensive historical research, many of the Russian Revival's works of art were characterized by symbolism and emphasized decorativeness. Painters like Nesterov were strongly influenced by medieval icons and medieval spirituality. The religious paintings of the period show a sensitive and sometimes profound understanding of Russia's religious heritage. During the last decades of the nineteenth century, patronage of the arts came from wealthy merchants and industrialists, among them Savva Mamontov and his wife, Elizaveta. The Mamontovs supported the new artists, establishing an artist colony at Abramtsevo. The workshop, school, and a church built there led to a popularization of medieval art and architecture. As the revival artists searched for new modes of expression, a new cultural movement, called The World of Art and represented by such artists as Vrubel, Benois, Bakst, Dobuzhinskii, Roerich, Bilibin, Lansere (Lanceray), Kustodiev, and Sapunov was accelerating Russian painting in the direction of new artistic discoveries and leading to the appearance of the Russian avant-garde. [B.B.] [Sources: Hamilton, Gray, Newmarch].