Roots of intellectual change

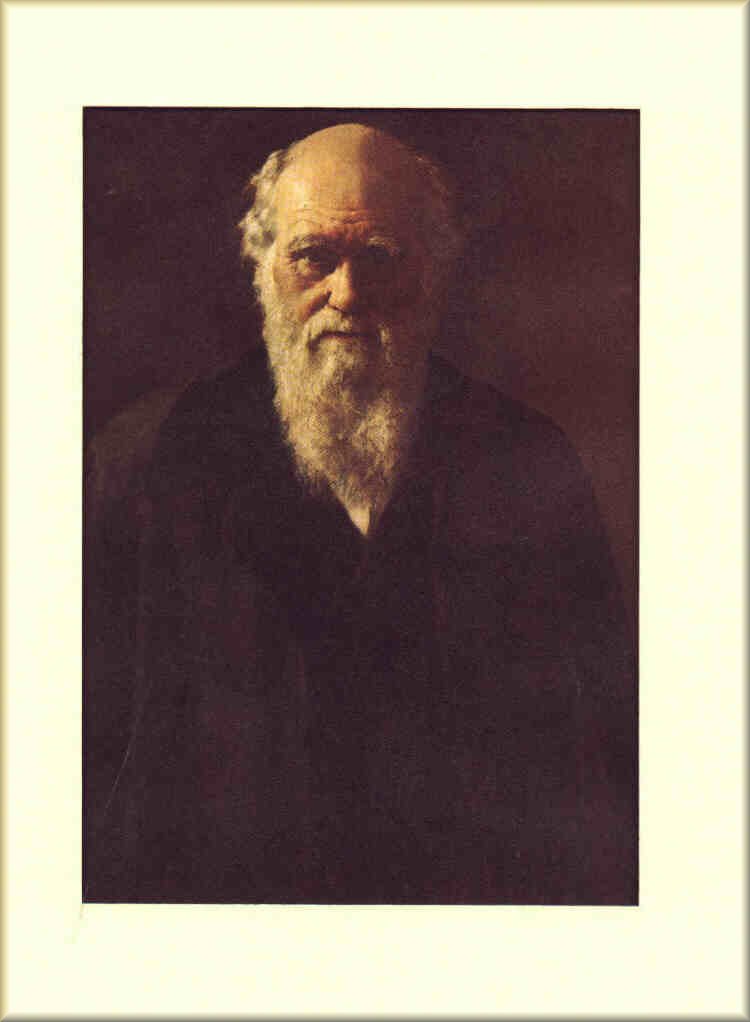

Roots of intellectual changeCharles Robert Darwin (1809-1882)

"Of these, the most important have been--the love of science--"

personal | experiences | initial findings | anomalies | change in view

"Darwin's whole trend of thought was against facile speculation, yet theories flowed freely through his mind ready for the essential tests of observation and experiment. He took twenty years of combined theorising and fact-finding to prepare his case for evolution in the face of a predominantly antagonistic world. He had to convince himself by accumulated evidence before he could convince others, and his doubts are as freely expressed as his convictions. His books lie like stepping-stones to future knowledge. Dogmatic fixity was wholly alien to his central idea."

Autobiography, p. 14, Introduction by Nora Barlow ( )

He was a grandchild of Erasmus Darwin, who wrote an eighteenth century study of evolution and of whose work, Darwin said," I had …read the Zoonomia of my grandfather, in which similar views [as Lamarck's] are maintained, but without producing any effect on me." He was the son of a gentleman, a collector of beetles, unusually squeamish at the sight of blood, disappointed his father with his choice of professional endeavors, circumnavigated the earth from 1831 to 1836, married his cousin Emma Wedgwood on 29 Januray1839, a member of his uncle Josiah Wedgwood II's family –the famous porcelain maker– and they raised ten children, although he was was chronically ill, and is buried in Westminster Cathedral beside one of his harshest critics, Sir John Herschel.

Comments from page 13, The Autobiography of Charles Darwin.

The Darwins were married on 29 January 1839 and were the parents of 10 children, three of whom died at early ages; his daughter Annie's death at the age of only ten shook Darwin's emotional confidence in the rationality and grace of the world as she was among the most gifted, brightest, and earnest of his children.

See David Krulewich, NPR, 12 February 2009. "Death Of Child May Have Influenced Darwin's Work."

• 1831, departure on the Beagle, under Captain Fitzroy's command

![]() September - October 1835: the Galapagos Islands off of the coast of Ecuador, South America.

September - October 1835: the Galapagos Islands off of the coast of Ecuador, South America.

• 1836, return to Britain

character | methods | writing | Origin's cause to write | Origin, reflection on | other works | his motives | voyage | grandfather

personal diary

"when I see these islands in sight of each other and possessed of but a scanty stock of animals, tenanted by these birds but slightly different in structure and filling the same place in nature, I must suspect they are varieties..."

1837, Darwin begins to keep "notebooks"

correspondence with John Gould, ornithologist, on Mimus, the mockingbirds.

The mockingbirds collected on three different islands of the Galapagos were three distinct species and not different varieties as Darwin had originally conceived them to be.

Meaning, the gradual origin of new species through geographical speciation (adaptive radiation), or separation from the ancestral population points to sufficient evidence for evolution by means of selective pressure.

for example:

South American, African and Asian monkeys.

Tigers in India and lions in Africa.

Horse-sized rodents in South America.

Absence of placental mammals in Australia.

Crocodiles in Africa, South America, and Florida.

Manatees or dugongs along the tropical coasts Asia, Africa & the Americas.

personal | experiences | initial findings | anomalies | change in view

character | methods | writing | Origin's cause to write | Origin, reflection on | other works | his motives | voyage | grandfather

1838, by the fall of this year Darwin adopted "natural selection" as the means by which species diverged from a common ancestral population.

September 18, 1838: Darwin read Thomas Malthus on the inverse relation of population and food's different growth rates: geometric versus arithmetic projection: from this struggle for existence he developed the above idea

1842-44, The preliminary essay written on species as mutable, the descent of species analogous to any individuals' lineage from parents and grandparents.

1844, Letter to Leonard Horner: "I always feel as if my books came half out of Lyell's brains....it [Principles of Geology] altered the whole tone of one's mind and therefore that when seeing a thing never seen by Lyell, one yet saw it partially through his eyes." (Stephen J. Gould, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory, p. 94.)

1851, the death of his daughter Ann

1858, The manuscript from Alfred Russell Wallace arrives

the death of Charles junior from scarlet fever (June 28) during the Lyell, Hooker discussion of the Wallace manuscript and what Darwin ought to do.

Darwin was tone deaf, yet loved the symphonies and overtures of Mozart, Handel and Beethoven. In the evenings his wife, Emma, who was quite an accomplished pianist (she was trained by Frederic Chopin), would play for him on her piano forte as he reclined on a nearby sofa.

character | methods | writing | Origin's cause to write | Origin, reflection on | other works | his motives | voyage | grandfather

Darwin seemed to be born with an innate interest in the natural world, but not until the Summer of 1826 did he read books about nature. During this time he read Reverend. Gilbert White's: "The Natural History of Selborne" and he gained a much wider appreciation for wildlife.

While attending Cambridge University, Darwin was further inspired to be a naturalist when reading: William Paley's: "Natural Theology." He also read literature by Sir John Herschel, "Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy" and Alexander von Humboldt's 7-vol. "Personal Narrative" of his South America travels.

During the Beagle voyage he always read Milton's "Paradise Lost" when he had a spare moment. But took with him Charles Lyell's"the Principles of Geology," which had the most profound impact on his ideas about nature. While living in London after the voyage, Darwin read some metaphysical books, but found that he was not well suited to them. It was during this same time in his life that he became fond of the poetry of William Wordsworth, and Samuel Coleridge.

In later years Darwin was very fond of novels by Jane Austen, and Elizabeth Gaskell, the poems of Lord Byron, and the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott. He did not enjoy novels with a depressing ending. His wife, Emma, would read novels to him twice a day while he reclined on a sofa, and he took great pleasure in this daily routine. He also enjoyed books of narrated travels.

He worked for approximately four hours per day, on good days when he was feeling well. Darwin ate breakfast alone at 7:45 every morning and lunch with his family from 1 to 1:30 in the afternoon. He attended to his correspondence in the afternoon took an hour or half-hours walk and ate dinner at 7:30 in the evening.

Hardin, Nature and Man's Fate, pp. 38-39.

character | methods | writing | Origin's cause to write | Origin, reflection on | other works | his motives | voyage | grandfather

Darwin wrote to Joseph Dalton Hooker, his confidant, during January, 1844, that "I am almost convinced (quite contrary to the opinion I started with) that species are not (It is like confessing a murder) immutable."

| The two men who shocked the complacency of Victorian Europe | |

|

|

Charles Robert Darwin |

Alfred Russel Wallace |

Table of Contents

| chapters | Origin of Species (1859) Darwin's book | sections | Alfred Russel Wallace's paper (1859) |

| 1 | Variation under Domestication |

“varieties in a state of domesticity” | |

| 2 | Variation under Nature |

2. | The Law of Population of Species |

| 3 | Struggle for Existence |

1. | “Struggle for existence” |

| 4 | Natural Selection |

||

| 5 | Laws of Variation Useful variation |

||

| 6 | Difficulties on Theory |

3. | perfect adaptation to the conditions of existence |

| 7 | Instinct | ||

| 8 | Hybridization Reversion of Domesticated varieties | ||

| 9 | On the Imperfection of the Geological Record | ||

| 10 | On the Geological succession of organic beings | ||

| 11 | Geographical Distribution (A) | ||

| 12 | Geographical Distribution (B) | ||

| 13 | Mutual Affinities of Organic Beings | ||

| 14 |

Recapitulation and Conclusion |

character | methods | writing | Origin's cause to write | Origin, reflection on | other works | his motives | voyage | grandfather

Voyage of the 'Beagle,' from December 27, 1831, to October 2, 1836.

"I had brought with me the first volume of Lyell's 'Principles of Geology,' which I studied attentively; and the book was of the highest service to me in many ways. The very first place which I examined, namely St. Jago in the Cape de Verde islands, showed me clearly the wonderful superiority of Lyell's manner of treating geology, compared with that of any other author, whose works I had with me or ever afterwards read."

"Fitz-Roy's temper was a most unfortunate one. . . . We had several quarrels; for instance, early in the voyage at Bahia, in Brazil, he defended and praised slavery, which I abominated, and told me that he had just visited a great slave-owner, who had called up many of his slaves and asked them whether they were happy, and whether they wished to be free, and all answered "No." I then asked him, perhaps with a sneer, whether he thought that the answer of slaves in the presence of their master was worth anything? This made him excessively angry, and he said that as I doubted his word we could not live any longer together."

"The glories of the vegetation of the Tropics rise before my mind at the present time more vividly than anything else; though the sense of sublimity, which the great deserts of Patagonia and the forest-clad mountains of Tierra del Fuego excited in me, has left an indelible impression on my mind."

"No other work of mine was begun in so deductive a spirit as this, for the whole theory was thought out on the west coast of South America, before I had seen a true coral reef. I had therefore only to verify and extend my views by a careful examination of living reefs. But it should be observed that I had during the two previous years been incessantly attending to the effects on the shores of South America of the intermittent elevation of the land, together with denudation and the deposition of sediment. This necessarily led me to reflect much on the effects of subsidence, and it was easy to replace in imagination the continued deposition of sediment by the upward growth of corals.

To do this was to form my theory of the formation of barrier-reefs and atolls."

Aukland, New Zealand Museum, Darwin exhibit and Collection

character | methods | writing | Origin's cause to write | Origin, reflection on | other works | his motives | voyage | grandfather

One Long Argument, by Ernst Mayr

The Origin of Species: or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, (1859)

In October 1838, that is, fifteen months after I had begun my systematic enquiry, I happened to read for amusement 'Malthus on Population,' and being well prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence which everywhere goes on from long-continued observation of the habits of animals and plants, it at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species. Here then I had at last got a theory by which to work; but I was so anxious to avoid prejudice, that I determined not for some time to write even the briefest sketch of it. In June 1842 I first allowed myself the satisfaction of writing a very brief abstract of my theory in pencil in 35 pages; and this was enlarged during the summer of 1844 into one of 230 pages, which I had fairly copied out and still possess.

But at that time I overlooked one problem of great importance; and it is astonishing to me, except on the principle of Columbus and his egg, how I could have overlooked it and its solution. This problem is the tendency in organic beings descended from the same stock to diverge in character as they become modified. That they have diverged greatly is obvious from the manner in which species of all kinds can be classed under genera, genera under families, families under sub-orders and so forth; and I can remember the very spot in the road, whilst in my carriage, when to my joy the solution occurred to me; and this was long after I had come to Down. The solution, as I believe, is that the modified offspring of all dominant and increasing forms tend to become adapted to many and highly diversified places in the economy of nature.

Early in 1856 Lyell advised me to write out my views pretty fully, and I began at once to do so on a scale three or four times as extensive as that which was afterwards followed in my 'Origin of Species;' yet it was only an abstract of the materials which I had collected, and I got through about half the work on this scale. But my plans were overthrown, for early in the summer of 1858 Mr. Wallace, who was then in the Malay archipelago, sent me an essay "On the Tendency of Varieties to depart indefinitely from the Original Type;" and this essay contained exactly the same theory as mine. Mr. Wallace expressed the wish that if I thought well of his essay, I should sent it to Lyell for perusal.

The circumstances under which I consented at the request of Lyell and Hooker to allow of an abstract from my MS., together with a letter to Asa Gray, dated September 5, 1857, to be published at the same time with Wallace's Essay, are given in the 'Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,' 1858, page 45. I was at first very unwilling to consent, as I thought Mr. Wallace might consider my doing so unjustifiable, for I did not then know how generous and noble was his disposition.

Charles Darwin, Autobiography, p.

The success of the 'Origin' may, I think, be attributed in large part to my having long before written two condensed sketches, and to my having finally abstracted a much larger manuscript, which was itself an abstract. By this means I was enabled to select the more striking facts and conclusions. I had, also, during many years followed a golden rule, namely, that whenever a published fact, a new observation or thought came across me, which was opposed to my general results, to make a memorandum of it without fail and at once; for I had found by experience that such facts and thoughts were far more apt to escape from the memory than favourable ones. Owing to this habit, very few objections were raised against my views which I had not at least noticed and attempted to answer.

character | methods | writing | Origin's cause to write | Origin, reflection on | other works | his motives | voyage | grandfather

My 'Descent of Man' was published in February, 1871.

As soon as I had become, in the year 1837 or 1838, convinced that species were mutable productions, I could not avoid the belief that man must come under the same law. Accordingly I collected notes on the subject for my own satisfaction, and not for a long time with any intention of publishing. Although in the 'Origin of Species' the derivation of any particular species is never discussed, yet I thought it best, in order that no honourable man should accuse me of concealing my views, to add that by the work "light would be thrown on the origin of man and his history." It would have been useless and injurious to the success of the book to have paraded, without giving any evidence, my conviction with respect to his origin.

But when I found that many naturalists fully accepted the doctrine of the evolution of species, it seemed to me advisable to work up such notes as I possessed, and to publish a special treatise on the origin of man. I was the more glad to do so, as it gave me an opportunity of fully discussing sexual selection--a subject which had always greatly interested me. This subject, and that of the variation of our domestic productions, together with the causes and laws of variation, inheritance, and the intercrossing of plants, are the sole subjects which I have been able to write about in full, so as to use all the materials which I have collected. The 'Descent of Man' took me three years to write, but then as usual some of this time was lost by ill health, and some was consumed by preparing new editions and other minor works. A second and largely corrected edition of the 'Descent' appeared in 1874.

My book on the 'Expression of the Emotions in Men and Animals' was published in the autumn of 1872.

I had intended to give only a chapter on the subject in the 'Descent of Man,' but as soon as I began to put my notes together, I saw that it would require a separate treatise.

My first child was born on December 27th, 1839, and I at once commenced to make notes on the first dawn of the various expressions which he exhibited, for I felt convinced, even at this early period, that the most complex and fine shades of expression must all have had a gradual and natural origin. During the summer of the following year, 1840, I read Sir C. Bell's admirable work on expression, and this greatly increased the interest which I felt in the subject, though I could not at all agree with his belief that various muscles had been specially related for the sake of expression. From this time forward I occasionally attended to the subject, both with respect to man and our domesticated animals.

Charles Darwin, Autobiography, p.

There seems to be a sort of fatality in my mind leading me to put at first my statement or proposition in a wrong or awkward form. Formerly I used to think about my sentences before writing them down; but for several years I have found that it saves time to scribble in a vile hand whole pages as quickly as I possibly can, contracting half the words; and then correct deliberately. Sentences thus scribbled down are often better ones than I could have written deliberately.

Having said thus much about my manner of writing, I will add that with my large books I spend a good deal of time over the general arrangement of the matter. I first make the rudest outline in two or three pages, and then a larger one in several pages, a few words or one word standing for a whole discussion or series of facts. Each one of these headings is again enlarged and often transferred before I begin to write in extenso. As in several of my books facts observed by others have been very extensively used, and as I have always had several quite distinct subjects in hand at the same time, I may mention that I keep from thirty to forty large portfolios, in cabinets with labelled shelves, into which I can at once put a detached reference or memorandum. I have bought many books, and at their ends I make an index of all the facts that concern my work; or, if the book is not my own, write out a separate abstract, and of such abstracts I have a large drawer full. Before beginning on any subject I look to all the short indexes and make a general and classified index, and by taking the one or more proper portfolios I have all the information collected during my life ready for use.

Charles Darwin, Autobiography, p.

character | methods | writing | Origin's cause to write | Origin, reflection on | other works | his motives | voyage | grandfather

Perception, memory, and observation

I have no great quickness of apprehension or wit which is so remarkable in some clever men, for instance, Huxley. I am therefore a poor critic: a paper or book, when first read, generally excites my admiration, and it is only after considerable reflection that I perceive the weak points. My power to follow a long and purely abstract train of thought is very limited; and therefore I could never have succeeded with metaphysics or mathematics. My memory is extensive, yet hazy: it suffices to make me cautious by vaguely telling me that I have observed or read something opposed to the conclusion which I am drawing, or on the other hand in favour of it; and after a time I can generally recollect where to search for my authority.

Some of my critics have said, "Oh, he is a good observer, but he has no power of reasoning!" I do not think that this can be

true, for the 'Origin of Species' is one long argument from the beginning to the end, and it has convinced not a few able men. No one could have written it without having some power of reasoning. I have a fair share of invention, and of common sense or judgment, such as every fairly successful lawyer or doctor must have, but not, I believe, in any higher degree.

On the favourable side of the balance, I think that I am superior to the common run of men in noticing things which easily escape attention, and in observing them carefully. My industry has been nearly as great as it could have been in the observation and collection of facts. What is far more important, my love of natural science has been steady and ardent.

character | methods | writing | Origin's cause to write | Origin, reflection on | other works | his motives | voyage | grandfather

This pure love has, however, been much aided by the ambition to be esteemed by my fellow naturalists. From my early youth I have had the strongest desire to understand or explain whatever I observed,--that is, to group all facts under some general laws. These causes combined have given me the patience to reflect or ponder for any number of years over any unexplained problem. As far as I can judge, I am not apt to follow blindly the lead of other men. I have steadily endeavoured to keep my mind free so as to give up any hypothesis, however much beloved (and I cannot resist forming one on every subject), as soon as facts are shown to be opposed to it. Indeed, I have had no choice but to act in this manner, for with the exception of the Coral Reefs, I cannot remember a single first-formed hypothesis which had not after a time to be given up or greatly modified. This has naturally led me to distrust greatly deductive reasoning in the mixed sciences. On the other hand, I am not very sceptical,--a frame of mind which I believe to be injurious to the progress of science. A good deal of scepticism in a scientific man is advisable to avoid much loss of time,"

Charles Darwin, Autobiography, p.

My success is by complex and diversified mental qualities and conditions. Of these, the most important have been--the love of science-- unbounded patience in long reflecting over any subject--industry in observing and collecting facts--and a fair share of invention as well as of common sense.Charles Darwin, Autobiography, p.

Aukland, New Zealand Museum, Darwin exhibit and Collection

character | methods | writing | Origin's cause to write | Origin, reflection on | other works | his motives | voyage | grandfather