Diatoms

The glass house of life

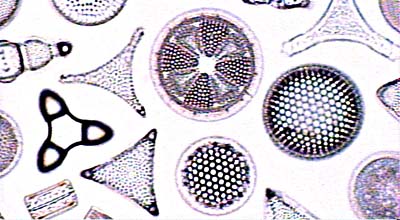

Diatoms are single-celled organisms which secrete intricate skeletons. These may be elongate, with a bilateral plane of symmetry, or they may be round and radially symmetrical. Many diatoms are slightly asymmetrical, though they generally fall into one of these two categories.

The Bacillariophyta are the diatoms. With their exquisitely beautiful silica shells, or frustules such as that of Odontella shown above at right, diatoms are among the loveliest microfossils. They are also among the most important aquatic microorganisms today: they are extremely abundant both in the plankton and in sediments in marine and freshwater ecosystems, and because they are photosynthetic they are an important food source for marine organisms. Some may even be found in soils or on moist mosses.

Diatoms have an extensive fossil record going back to the Cretaceous; some rocks are formed almost entirely of fossil diatoms, and are known as diatomite or diatomaceous earth. These deposits are mined commercially as abrasives and filtering aids. Analysis of fossil diatom assemblages may also provide important information on past environmental conditions.

Within their silica walls, diatoms show a typical level of eukaryote organization. Living diatoms contain several chloroplasts, where photosynthesis takes place.

![]()

http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/archaea/archaea.html

Diatoms may be divided into two main classes. The centrate diatoms, or Centrobacillariophyceae, are generally radially symmetrical, like the specimen of Melosira shown above at left. Pinnularia, at right, is a pennate diatom, member of the Pennatibacillariophyceae, showing its typical bilateral symmetry.

Diatoms may be divided into two main classes. The centrate diatoms, or Centrobacillariophyceae, are generally radially symmetrical, like the specimen of Melosira shown above at left. Pinnularia, at right, is a pennate diatom, member of the Pennatibacillariophyceae, showing its typical bilateral symmetry.

Members of both classes may be found in either fresh or salt water, though centrate forms tend to predominate in marine habitats, while pennate diatoms are more typical of freshwater environments.

The scheme most often used currently divides all living organisms into five kingdoms: Monera (bacteria), Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia. This coexisted with a scheme dividing life into two main divisions: the Prokaryotae (bacteria, etc.) and the Eukaryotae (animals, plants, fungi, and protists).

Recent work, however, has shown that what were once called "prokaryotes" are far more diverse than anyone had suspected. The Prokaryotae are now divided into two domains, the Bacteria and the Archaea, as different from each other as either is from the Eukaryota, or eukaryotes. No one of these groups is ancestral to the others, and each shares certain features with the others as well as having unique characteristics of its own.

Recent work, however, has shown that what were once called "prokaryotes" are far more diverse than anyone had suspected. The Prokaryotae are now divided into two domains, the Bacteria and the Archaea, as different from each other as either is from the Eukaryota, or eukaryotes. No one of these groups is ancestral to the others, and each shares certain features with the others as well as having unique characteristics of its own.

Within the last two decades, a great deal of additional work has been done to resolve relationships within the Eukaryota. It now appears that most of the biological diversity of eukaryotes lies among the protists, and many scientists feel it is just as inappropriate to lump all protists into a single kingdom as it was to group all prokaryotes.

http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/alllife/images/domains_small.gif

http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/alllife/threedomains.html

Dinoflagellates are unicellular protists which exhibit a great diversity of form. The largest, Noctiluca, may be as large as 2 mm in diameter! Though not large by human standards, these creatures often have a big impact on the environment around them. Many are photosynthetic, manufacturing their own food using the energy from sunlight, and providing a food source for other organisms. Some species are capable of producing their own light through bioluminescence, which also makes fireflies glow. There are some dinoflagellates which are parasites on fish or on other protists.

The most dramatic effect of dinoflagellates on life around them comes from the coastal marine species which "bloom" during the warm months of summer. These species reproduce in such great numbers that the water may appear golden or red, producing a "red tide". When this happens many kinds of marine life suffer, for the dinoflagellates produce a neurotoxin which affects muscle function in susceptible organisms. Humans may also be affected by eating fish or shellfish containing the toxins. The resulting diseases include ciguatera (from eating affected fish) and paralytic shellfish poisoning, or PSP (from eating affected shellfish, such as clams, mussels, and oysters); they can be serious but are not usually fatal.