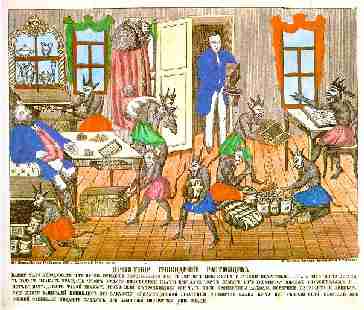

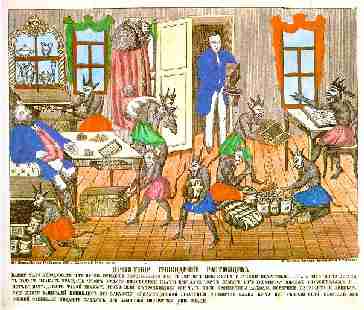

The lubok, also known as folk picture, popular print, or broadside, probably derives its name from the Russian word for the bast or the inner bark of a tree. The print's unique style is a skillful mix of the traditions of the Western European print and the heritage of Russian icon painting and manuscript illustration. Although initially dependent on Western examples, the Russian printmakers soon began adapting, changing, expanding, or altering their sources to arrive at cheerful, bright, expressive images. The lubki were cheaper than icons, easy to disseminate, and more responsive to the needs of the people or to the political, historical, or social events in Russia and abroad.

In the beginning, the lubok was made from wooden boards (xilography), which imposed on it a degree of simplicity, monumentality, and expressiveness of design. In the early eighteenth century, however, copper engraving began to replace xilography, changing the stylistic features of the prints by allowing the compositions to become more elaborate and to include many figures, details, and many lines of text in each picture. This affected the style of the print, which lost its monumentality and the clarity of its design. The wide range of topics covered by the prints makes their classification by subjects difficult, but such categories as religion, satire, everyday life (genre), clowns and jesters, information and news, and literature leave only a small number of images in a separate category of miscellaneous pictures. The earliest prints were religious -- either intended to provide a cheap substitute for the expensive icons, or to acquaint the public with moral and didactic stories and parables from the Bible, the Synaxarion, the Paterikon, and the Great Mirror of Examples. Because of Peter the Great's reforms and secularizing policies, religious prints were forced to share their leading role with satirical ones and with those which depicted events from everyday life. Early satirical prints primarily targeted Peter and his wife; later, the satire was directed at loose morals and maritial infidelity, vanity, usury, greed and avarice, gluttony, bribe-taking, gambling, snobbery, laziness, and drunkenness. In many instances, one can find close analogies in the satire of these prints to the moral and didactic parables of religious lubki.

During the reigns of Anna Ioannovna and Elizabeth Petrovna, prints with dwarfs, clowns, and jesters became popular. Copied from French prints of Jacques Callot, the Western clowns and jesters quickly turned into beloved Russian characters, Farnos, Pigasya, Foma and Yerioma.

The reign of Catherine II put an end to the popularity of clowns and jesters; in their stead, the market was flooded with scenes galantes and catalogues of beauty marks, color symbolism, and advertisements.

The prints classified as informative and news-oriented introduced the public to unusual and amusing freaks, monsters, and natural phenomena in Russia and abroad; later, the prints described real historical events and portraits of important military leaders.

The literary prints drew primarily from translated adventure novels, fascinating and attractive to the readers because of their exotic settings, chivalric element, and sexual content unknown in medieval Russian literature. This process of secularization, very clearly visible in the Russian lubok, is not only a result of Peter the Great's modernization of Russia, but of the seventeenth century influence of the baroque in literature, art, and everyday life, as well as of the schism in the Russian Orthodox Church caused by the reforms of Patriarch Nikon. The everyday life (genre) prints concentrated on depiction of street vendors, people working and playing, Semik and Maslenitsa customs and celebrations, entertaining guests, flirting, happy and unhappy love, parting and longing. Finally, miscellaneous prints showed such things as Zodiac signs, images of birds and animals, fortune-telling and divinations, and the world turned inside out. The prints preached, taught, educated, amused, astonished, and brought laughter to the readers. And despite the fact that in the second half of the nineteenth century the lubok was considered something crude and primitive (an art form unworthy of an educated person's attention), at the end of the nineteenth and at the beginning of the twentieth century, it rose, like a Phoenix, from the ashes to inspire the artistic elite with its bold colors, clear compositions, decorativeness, funny characters, and robust language.

The compositions and colors of the paintings of Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, leaders of Russian neo-primitivism were deeply influenced by the lubok; Vasili Kandinsky called it "a marvel;" Stravinsky's ballet Petrouchka and Rimsky-Korsakov's opera Golden Cockerel had sets designed in the lubok style, while the works of Ivan Bilibin, one of the greatest Russian illustrators and designers, consistently show unmistakable and profound influence of those once popular prints. Expressing the customs, feelings, desires, hopes, beliefs, and superstitions of the people, the lubok is not only a mirror of the Russian soul, but also a unique lens through which one can look at Russian culture .

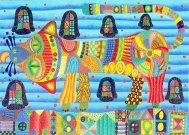

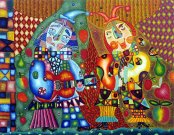

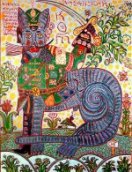

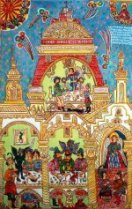

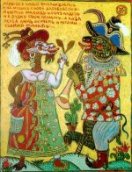

Today, some artists return to the lubok tradition, attracted by the prints' brightness and colors. Sergei Gorshkov, born in 1963, a graduate of the Voronezh Art School, creates works, which he calls "conceptual lubok." As his Internet presentation claims, his images resemble the art of a fair, and attempt to combine traditional folk art (lubok) with modern surreal imagery and ideas. The paintings represented here, all painted in 1994, are The Cat of Kazan, (oil on canvas, 100 x 80 cm), Bear and Goat Having Fun (oil on canvas, 51 x 64 cm), and Supper of the Righteous and the Unrighteous (oil on canvas, 100 x 150 cm). In comparison to the particular lubok which inspired them, they are more fanciful, more decorative, richer in color, and sometimes include inscriptions dealing with political icons. For instance, the Supper includes a hackneyed, but in this context irreverend and funny inscription related to the Soviet slogan "Lenin lived, Lenin lives, Lenin will live." In Gorshkov's version, the inscription reads "Lenin is more alive than all living" (Lenin zhivee vsekh zhivykh).

Another artist who enjoys great success and is profoundly influenced by lubok, Vladimir Fomin, was born in Tomsk in 1963 and graduated from Krasnoselsk Jewelry Institute. After that, having found his inspiration in the folk art, Fomin studied with folk artists in Central Russia. He paints beautiful, bright, cheerful canvasses. Some of them, as the three reproduced below, may have real lubok antecendents. Motley Cat (oil on canvas, 50 x 70 cm, 1998), Pierrot and Harlequin: A Gift to Paul Cezanne (oil on canvas, 55 x 70 cm, 1996), and Feast of Clowns (oil on canvas, 100 x 150 cm, 1992) may be related to the Cat of Kazan, prints with court jesters and prints about Foma and Yerioma. Fomin's works seem to cherish a combination of naive folk art and abstraction; such a combination is foreign to lubok proper, but quite common in the art of the avant-garde (Goncharova, Filonov). In general, Fomin's works are much more intellectual than lubok, often deriving from literary sources (Kalevala, Peer Gynt, Nikolai Gumilev). Fomin asserts that for him the most important thing in art is beauty. And indeed, his modern "lubki" are a revelation of freshness and optimism, an unabashed celebration of color, rhythm, and pattern.