The Ideal Women’s Club

“We pledge ourselves to make every effort to accomplish what we undertake. We will not be “slackers” or afraid of hard work. If we undertake to do something too big for one of us to do alone, we will all take hold and help. If it is too big for all of us, we will get others to help; only it must be done some way, by someone, at some time. We pledge each other not to talk of what we are going to do more than is necessary until it is done. Then we will try to find something else to do.”

In 1881, a Chicago entrepreneur named Loring Chase planned Winter Park with eastern section for the whites and the western section African Americans. Hannibal Square, the African-American community was named after a heroic Carthaginian general who lived between 247 and 182 B.C. and fought Rome. Ironically, the same year Chase founded Winter Park; the Florida State Legislature introduced its third Jim Crow law making interracial marriages illegal. Hannibal Square thrived despite segregation. There were black owned businesses, such as grocery stores, drugs stores, beauty shops and more. However, as Jim Crow laws began to suppress African-American social, political, and economic opportunity and the overall southern economy slowed, Hannibal Square suffered like many African-American communities.

In 1937, when Mary Lee De Pugh arrived in Hannibal Square the community was struggling. De Pugh moved from Illinois with her husband, Baker, and her widowed boss, Mrs. Maud Kraft. An amiable boss, Kraft bought Mary Lee DePugh and her husband a home in the black community so they wouldn’t have to work as live-ins. One evening Mary Lee DePugh was invited to a performance given by students from Hannibal Square Elementary in the school’s auditorium. When Mary Lee DePugh watched the performance, she noticed that the theatrical performance didn’t have the proper auditorium and was lacking props and costumes. Mary Lee DePugh realized that the black community was in desperate need of a community center. In Illinois, she had been involved in the Matilda Dunbar Club, where she and other women would interact socially, engage intellectually, and come up with ideas to help out the community. With this in mind, on July 29, 1937 Mary Lee DePugh established the Ideal Women’s Club. Mary Lee DePugh was also a Sunday school teacher. Thus, she encouraged the Ideal Woman’s Club to have a strong connection to the religious community. Most of the women that were a part of the Ideal Women’s Club had to work, but most of them were off on Thursday. Therefore, meetings were held twice a month on Thursday nights. In the beginning, the women didn’t have a clubhouse, so meetings would be held in members’ homes and in the local library.

Mrs. Rose Bynum, daughter of Oliver Charlton, was the first treasurer of the Ideal Woman’s Club. In an interview with Nancy Doty, she reflected upon the memories she had of the Ideal Woman’s Club. “They were fortunate enough to have a lady here with motivation. She was from Chicago and her name was Mary Lou DePugh. She lived on Fairbanks where Holler Chevrolet is now. As a little girl I would go and sit and listen to her, and I would help her write letters. There was a white lady, and her name was Mrs. Peasley. She would get the other ladies together and their families, and they would come over and have dinner on Thursdays.”

As a child, Rose was an active member of her community writing letters with Mary Lee DePugh to the state senate requesting funds to expand the ever-growing Ideal Woman’s Club. Rose reflected that, “…as a little girl I would go and sit and listen to her, and I would help her to write letters.” Rose had tremendous respect and admiration for the contributions Mary Lee DePugh put towards the expansion of the Ideal Woman’s Club.

The Ideal Woman’s Club not only helped the black community socially, but also inspired others to help the community. In the 1930’s Mrs. Chaney Laughlin was concerned for the health of her sick, elderly neighbor. She gathered a group of friends together from the Ideal Woman’s Club and together they organized the Benevolent Club. After sewing bees, and dinners, they were able to gather enough money to care for Mrs. Laughlin’s sick neighbor and “also start the first unit of the home, which was then used as a medical and dental clinic on Morse Boulevard and Pennsylvania Avenue.”

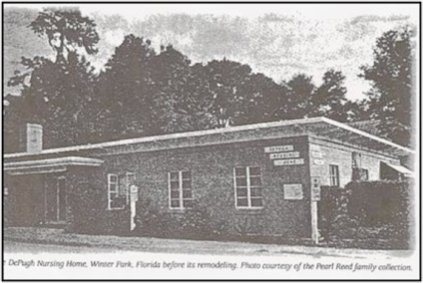

In the late 1940s’ the women took on the “Nursing Home Project.” The nursing home would be named The DePugh Nursing Home in honor of Mary Lee DePugh, the founder of the Ideal Woman’s Club. Members of Rollins College Interracial Committee (RCIC) supported the nursing home project. Fred Rogers, chairman of RCIC from 1950 to 1951 explained, “During the past month we have been soliciting funds for The DePugh Nursing Home. The colored people of Winter Park started a drive to raise money for a local nursing home which would act as a hospital-clinic. Winter Park is in dire need of such a building, since there is no colored doctor in the town, and an Orlando doctor (negro) asks $8.00 a visit from patients in Winter Park. The home would include a minor operating room and a delivery room, plus room for 10 patients. The goal of the drive has not yet been reached, yet it is clearly in view.” By 1954 the Benevolent Club had 5,000 dollars for the nursing home. In that same year, Winter Park philanthropist R.T. Miller challenged the group to raise $15,000. He gave the Benevolent Club an additional $15,000 for meeting this goal. With $30,000 the group was able to start construction on the Mary Lee DePugh Nursing Home. January 25, 1956 was the opening ceremonies for the home, and the day the first patient was admitted. The DePugh Nursing home was equipped with 28 beds, two full time and part time registered nurses, fourteen nurse’s assistants and a full time custodian. Not only did the Ideal Woman’s Club give land to the DePugh Nursing Home, they were also generous enough to open up their kitchen to the patients in the nursing home. A striving institution for years, the Ideal Woman’s Club continues to provide a sense of community for the Winter Park community.

Notes:

Bynum, Rose. Interview with Nancy Doty. Winter Park Historical Association 17 Mar.

"Jim Crow Laws: Florida." The History of Jim Crow. New York Life. 10 Oct. 2007 <http://www.jimcrowhistory.org/geography/geography.htm>.

"Jim Crow Laws: Florida." The History of Jim Crow. New York Life. 10 Oct. 2007 <http://www.jimcrowhistory.org/geography/geography.htm>.

Shorefront. Chicago: History, News and Events on Chicago's Suburban North Shore, 2001

Wright, Edwin. "The History of DePaugh Nursing Home." DePugh Nursing Center Newsletter 1994: 1-3.

Additional Editorial Work By Rebecca Webb

Central Florida has an interesting and complex history that is under-explored in many ways. As a historian of the United States with special interest in urban development and planning, I have been intrigued by the people, places, and institutions in the region. To bolster student understanding of historical change, I have create a number of digital projects focused on local history. Supported by service learning grants from the college and designed to utilize archival sources, Historic Winter Park is an ongoing learning initiative to document the unique stories in the local community. Created by students in my history survey classes, these entries represent hands on archival research that incorporates unique materials from the Olin Library Special Collection and Archive, Winter Park Public Library, field work, and oral histories. Find more information on about digital history from my homepage.