Natural History and ideas in China

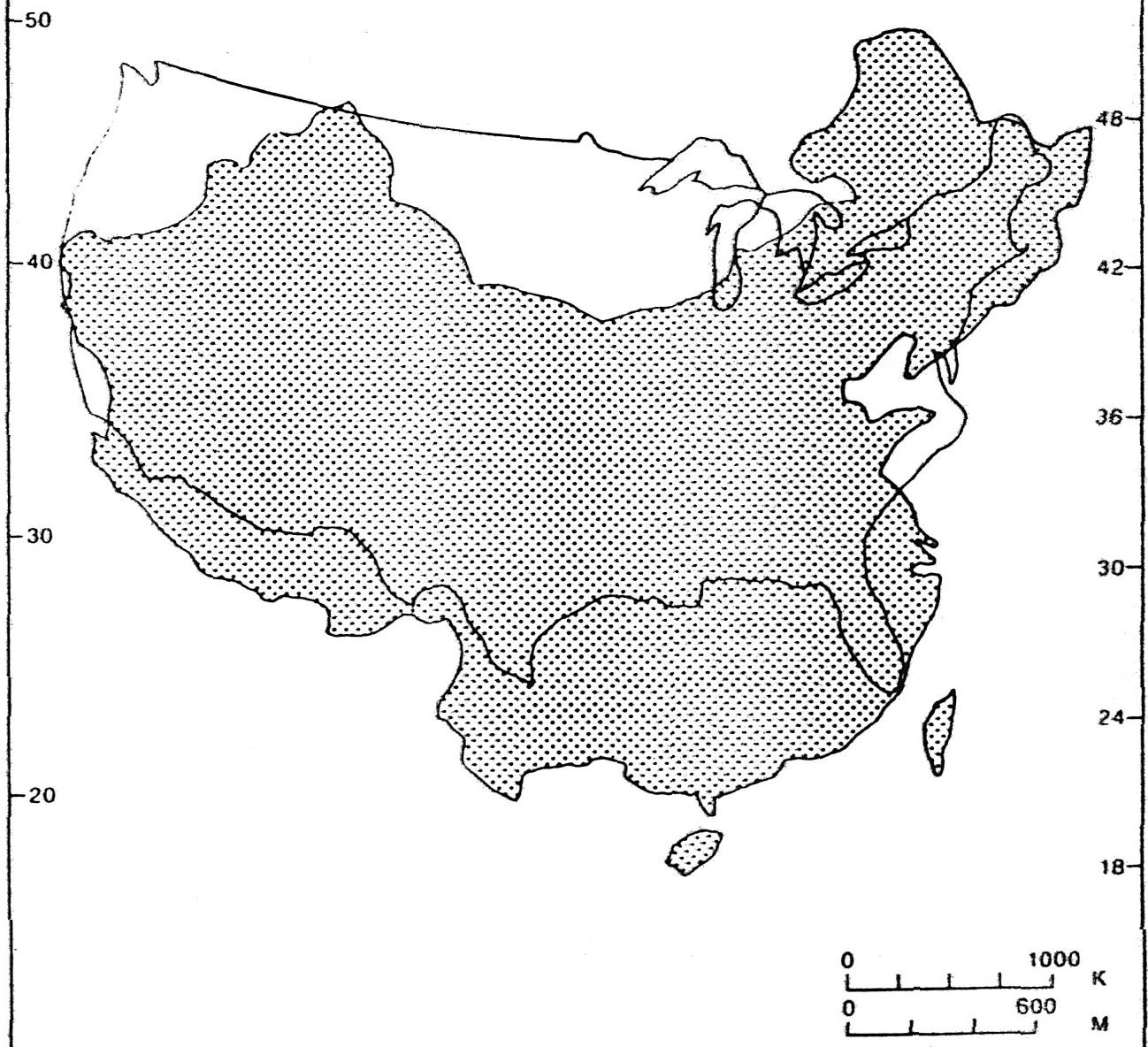

China also has the most diverse flora of any country in the North Temperate zone.

China's is enormously rich. Some 31,000 plant species are native to China, representing nearly one-eighth of the world's total plant species, including thousands found nowhere else on Earth. By comparison, the United States and Canada combined contain about 20,000 native plant species.

China is the only country on Earth where there are unbroken connections among tropical, subtropical, temperate, and boreal forests.

This unbroken connection has led to the formation of rich plant associations rarely seen elsewhere in the world. Many genera of plants which are known only from fossil records in North America and Europe are represented in China by living members. Food and vegetable crops from China have had international signififcance, although prehistoric remains of rice have been found near Shanghai, in Eastern India and Thailand. The Silk route alone linking Han China and Roman regions is evidence of the connections that make Chinese floral contributions of great significance to world history and population growth.

This unbroken connection has led to the formation of rich plant associations rarely seen elsewhere in the world. Many genera of plants which are known only from fossil records in North America and Europe are represented in China by living members. Food and vegetable crops from China have had international signififcance, although prehistoric remains of rice have been found near Shanghai, in Eastern India and Thailand. The Silk route alone linking Han China and Roman regions is evidence of the connections that make Chinese floral contributions of great significance to world history and population growth.

Similarities between the plants of China and North America

Mainland China and the continental United States share a common latitude and similar-sized land areas. The climates in much of the two regions are also similar, especially in the eastern halves. Many plant species that were once widespread throughout the entire northern hemisphere were wiped out by glaciation in North America but survived in China. Nearly 120 genera in 60 families of plants have disjunct populations in eastern Asia and temperate North America, relicts of the once widespread flora.

Mainland China and the continental United States share a common latitude and similar-sized land areas. The climates in much of the two regions are also similar, especially in the eastern halves. Many plant species that were once widespread throughout the entire northern hemisphere were wiped out by glaciation in North America but survived in China. Nearly 120 genera in 60 families of plants have disjunct populations in eastern Asia and temperate North America, relicts of the once widespread flora.

Knowledge of the Chinese flora is essential to understand floristic composition and interpret the fossil records of Europe, North America, and temperate Asia.

Many genera (e.g., Ginkgo, Metasequoia, Pseudolarix, Cercidiphyllum) which are known only from fossil records in North America and Europe, are extant in China. Metasequoia is one of the best known examples of taxa that were once widespread but now have very limited distributions. This genus was first known only from fossil remains and was thought to be Sequoia. In 1948, soon after botanists recognized it as a new genus (Metasequoia), a stand of living trees was discovered in central China. This genus, which once covered Asia, Europe, and North America, is now represented in the wild by only about 5,000 individuals in China. Cultivated trees outside of China have been grown from seeds sent to the West in 1947, including some given to and flourishing at the Missouri Botanical Garden and the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. They are elegant reminders of the past shared by the floras of Asia, Europe, and North America.

The use of plants by the Chinese

Throughout their centuries-old tradition, the Chinese discovered and adapted native plant resources for use as food, spices, and medicine. Several thousand species of Chinese plants are now cultivated throughout the world, including short-grain rice, tea, soybeans, oranges, cucumber, lemons, peaches, apricots, ginger, anise, and ginseng. Hundreds of Chinese species (e.g., rhododendrons, magnolias, camellias, viburnums, gardenias, jasmines, forsythias and primroses) are cultivated as ornamentals worldwide.

Throughout their centuries-old tradition, the Chinese discovered and adapted native plant resources for use as food, spices, and medicine. Several thousand species of Chinese plants are now cultivated throughout the world, including short-grain rice, tea, soybeans, oranges, cucumber, lemons, peaches, apricots, ginger, anise, and ginseng. Hundreds of Chinese species (e.g., rhododendrons, magnolias, camellias, viburnums, gardenias, jasmines, forsythias and primroses) are cultivated as ornamentals worldwide.

http://flora.huh.harvard.edu/china/mss/plants.htm

Five Phases (n, pl) the relationship of nature's five elements (water, wood, fire, metal, and earth) to various natural cycles and phenomena. In Taoism, each of the five elements corresponds to a time of day, direction, and season. Movement from one phase to the next occurs in defined sequences. For instance, water (night, north, winter) eventually becomes wood (morning, east, spring). The Five Phase system also includes the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac (for example, the rat and pig are water signs). The movements of the Five Phases are rooted in the cycles of yin and yang.

| Phases |  |

|

|

|

|

| Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water | |

| Direction | East |

South |

Center |

West |

North |

| Season | Spring |

Summer |

Late Summer |

Autumn |

Winter |

| Climate | Windy |

Hot |

Damp |

Dry |

Cold |

| Age | Birth |

Childhood |

Adulthood |

Old age |

Death |

| Color | Blue Green |

Red |

Yellow |

White |

Black |

| Motive | Strength, warmth, |

Expansion, activity |

Nurturance, balance,

coolness |

cold, stiff, hard |

Fluidity, movement, |

| Emotions | Anger |

Hot |

Pensiveness |

Sadness, grief |

Fear, fright |

| Sound | Shouting |

Laughing |

Singing |

Weeping |

Groaning |

| Taste | Sour |

Bitter |

Sweet |

Pungent |

Salty |

| Yin Channel | Liver |

Heart |

Spleen |

Lungs |

Kidneys |

| Yang Channel | Gall Bladder |

Small Intestine, Pericardium |

Stomach |

Large Intestine |

Bladder |

| Excessive Behavior | Rising energy |

Slow, scattered

energy |

blocked energy |

Weak energy |

Chaotic energy |

| Stages | Birth and regrowth |

Upward growth |

Harvest |

Decline and decay |

Death and rebirth |

| Disharmony detectable In | Eyes, nails |

Tongue, facial

complexion |

Mouth,lips |

Nose, skin |

Ears, hair |

![]()

Who was who in China?

Wang Chung

The Han dynasty scholar Wang Chung was a bitter enemy of most forms of fortune-telling and wrote a book entitled Discourses Weighed in the Balance (Lun Heng) which gives us some idea of the types of fortune-telling practices common during his lifetime (27-97 AD).

Shen Kua Dream Pool Essays c. 1086

Meng Yuan-Lao

Dream of the glories of the eastern Capital

c. 1126

Lou Shu Pictures of Tilling and Weaving scrolls, 1145

Is "the first sustained pictorial exploration in Chinese history of the technologies and te chniques used to produce riece and silk.”

Roslyn Lee Hammers, “The Square-Pallet Pump in Lou Shu’s Pictures of Tilling and Weaving,“ p. 133, Technology and Culture (46:1) January 2005.

Cultivated Landscapes: Reflections of Nature in Chinese Painting

Selections from the Collection of Marie-Hélène and Guy Weill

Remote Valleys and Deep Forests (detail 1), dated 1678

Liu Yu (Chinese, act. ca. 1650–after 1711)

Remote Valleys and Deep Forests (detail 1), dated 1678

Liu Yu (Chinese, act. ca. 1650–after 1711)

Handscroll; ink and color on paper; 10 5/8 x 144 1/8 in. (27 x 366 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Narcissus

Zhao Mengjian (Chinese, 1199–before 1267)

Handscroll; ink on paper; 13 1/16 x 146 1/2 in. (33.2 x 372.2 cm)

Ex coll.: C. C. Wang Family

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Scholar Viewing a Waterfall

Ma Yuan (Chinese, active ca. 1190–1225)

Album leaf; ink and color on silk; 9 7/8 x 10 1/4 in. (24.9 x 26 cm)

Ex coll.: C. C. Wang Family

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Old Trees, Level Distance (detail of left half)

Guo Xi (Chinese, ca. 1000–ca. 1090)

Handscroll; ink and color on silk; 13 3/4 x 41 1/4 in. (35.9 x 104.8 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York