An Ecological Tragedy in Lake Apopka

"Apopka: People of the Lake"

"superphosphate-fed foods feed me,…

who would dare to supersede me?"

"Superman," John Updike, (1955)

Joseph Siry

These casualties in the fields of Lake Apopka's Shores in the war of man against

nature are the women, children and men --migrant farm workers – who are the

actual canaries in the coal mine that is the industrial agricultural production

system that is Florida's rural disgrace. As Geraldean Matthew said so directly,

"We fed America all our life." Born in Belle Glade, Florida the Matthew's

family moved two-hundred miles north to the citrus orchards and vegetable fields of Lake Apopka in the

upper Ocklawaha River Valley in the early 1960s because of the lure of orange

and grapefruit picking that could bring in "good money." When compared

to the sugar and tomato fields of South Florida, the conditions for stoop labor and orchard harvesting seemed to be a step out of despair.

Matthew said so directly,

"We fed America all our life." Born in Belle Glade, Florida the Matthew's

family moved two-hundred miles north to the citrus orchards and vegetable fields of Lake Apopka in the

upper Ocklawaha River Valley in the early 1960s because of the lure of orange

and grapefruit picking that could bring in "good money." When compared

to the sugar and tomato fields of South Florida, the conditions for stoop labor and orchard harvesting seemed to be a step out of despair.

"They said that money grew on trees," as she recalls. "so we

came to Apopka, my brothers and sisters." Here Mrs. Matthew's labored for

forty years picking celery, cabbage, fruit, and vegetables for our plates and

pantries. C. S. Lewis once argued that "What we call 'Man's power over Nature' turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument." While migrant families endured the pain and promise of these farms beside the lakeshores the full measure of Lewis' oft quoted statement became manifest to only a few observers, even in retrospect.

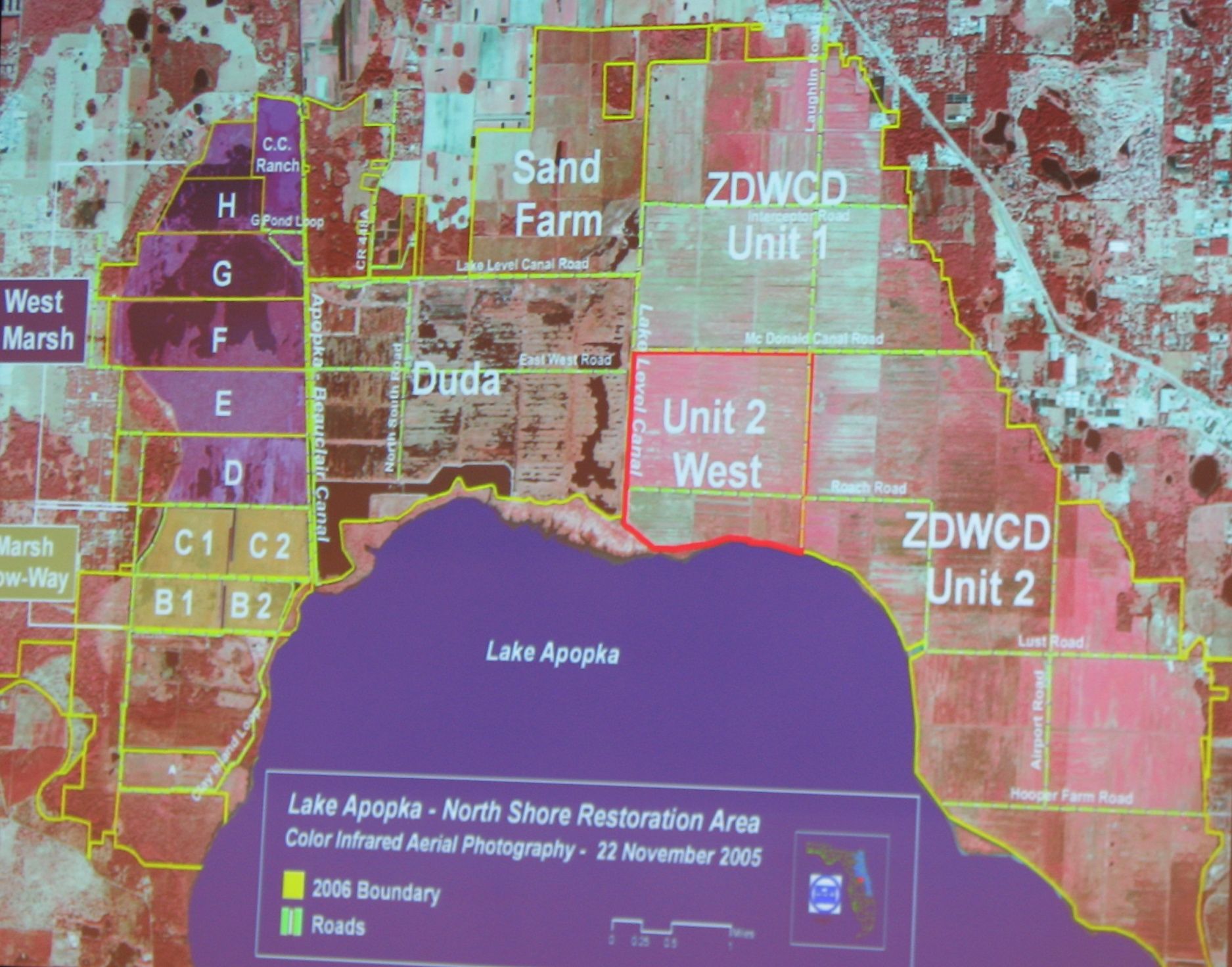

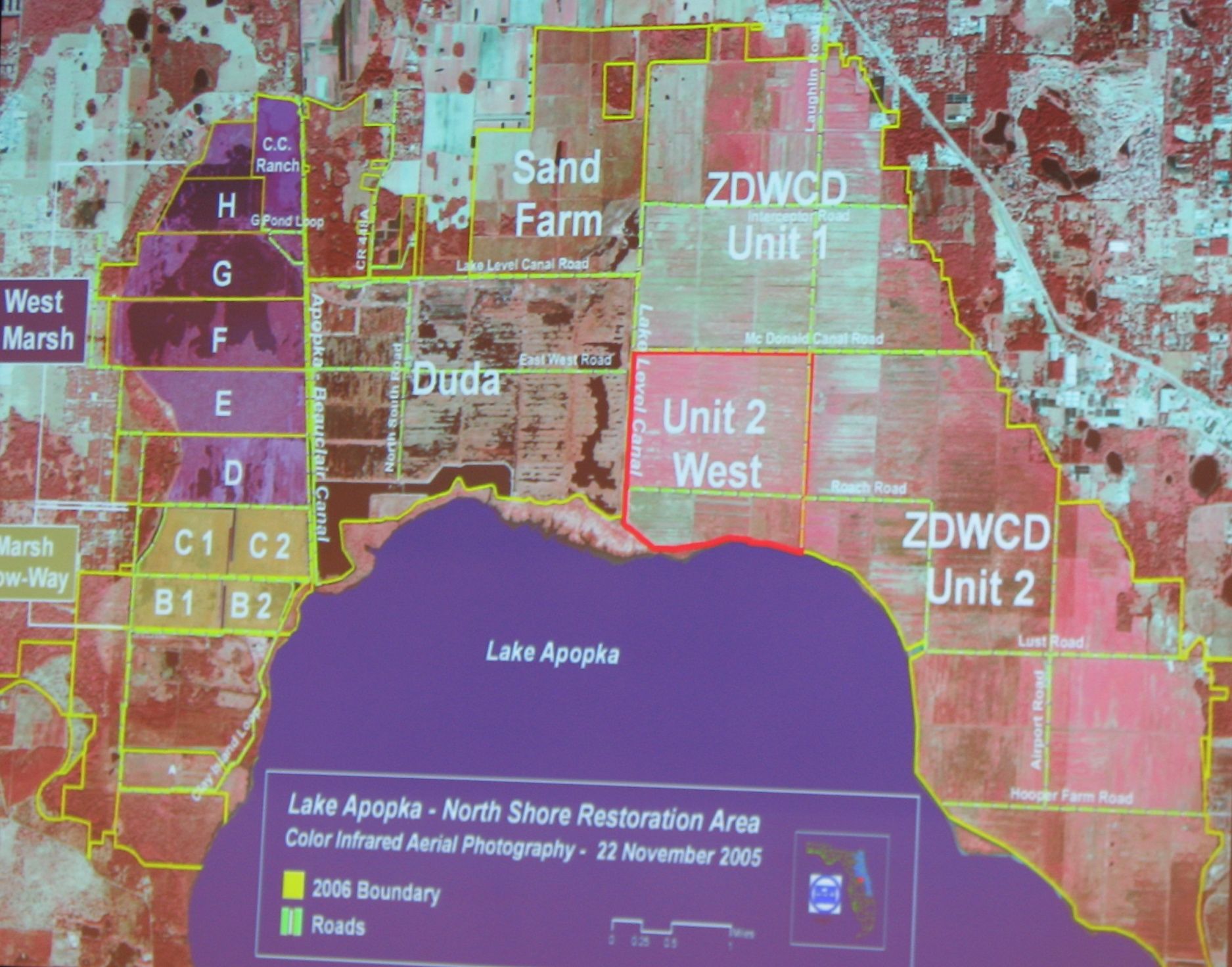

Once the premier bass fishery in the state, Lake Apopka had been drained

and partially surrounded by dikes in 1941 under government programs to turn lake bottom into farmland.

Called reclamation, this extension of the dredge and fill attitude exhibited

by the swamplands acts of the 1850s–a federal giveaway of land to the states–converted a 1000 acres of land adjoining the northern shore of the lake into

agricultural land with richly organic, peat-like, soils locally referred to as muck.

With the war production boom placing a premium on food the initial prosperity

of the fields encouraged an expansion of agriculture and the need for stoop

labor to harvest the fields. So notorious was the wage peonage system that sprouted

beside the celery or the corn and between the rows of cabbage, that in 1960 CBS

news ran a program just before Thanksgiving called "Harvest of Shame"

exposing the plight of migrant workers. The documentary starts in Immokallee

Florida between Lake Okeechobee and the Gulf beaches of Naples and Fort Myers

and proceeds to lay bare the disgrace of people enslaved working in the field

of the richest nation on earth. Geraldean Matthew, Betty Dubois her friend, and Linda Lee

could have been the African American children that this Edward R. Murrow documentary

exposed to the nation. Unknown to the boosters of the nation's market economy, these tainted fields and their exposed laborers would become both intrinsic participants in and a forgotten measure of environmental justice in this ongoing ecological tragedy.

Working for pennies a day, living in shacks, and denied education due to the

migratory character of field work in North America, the families worked in fields

whose days were literally numbered because of the soil chemistry of reclaimed

organic materials. The reeds, rushes, cattails and dumb cane that grow along

the shores of such a shallow lake in the hot subtropical sun rapidly decay contributing

to the organic matter of the submerged–waterlogged–soils. They grow so fast

in some seasons that there is little time for them to decay and instead the

carbon captured in the roots and stems stays locked in the dark soils we call

muck. In the submerged state, these conditions are called anoxic, because the

oxygen required to further breakdown the organic molecules in the vegetation

cannot penetrate the mud.

In summer when air and water temperatures rise, the oxygen levels

in the lakes drop. This is sort of like a deep freeze for the accumulating material

that makes the muck such a robust producer of crops. Nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur

and all the trace elements like potassium and magnesium the healthy growing

bodies need are readily available to the vegetables that Geraldean Matthew,

Betty Dubois, Linda Lee, and their families planted, weeded, and harvested for thirsty

some odd years. All the while the muck soils were exposed to oxygen, during

the growing season, however they literally were being consumed faster than the

accumulated wealth of the lakeshore could sustain. Thousands of years the muck

had accumulated and in these women's lifetimes, or less the oxidation of organic

matter exposed to the heat and the ultraviolet radiation dissolved the now dry

soils and literally they were evaporated by aerobic bacteria into the hovering humid sky. Even seasonal

flooding of the land between crops could not forestall the loss in the growing

season. The richness of an eternity of time before the arrival of the levees

and the drainage ditches was baked away in the torrid sun, while day workers

toiled in the fields of their landlords.

The solution to such a rapid loss of soil, so good for growing vegetables,

was a technical application to adjust what engineering could not forestall.

With the application of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers and herbicides to

kill the perennial weeds production was maintained. It became only another technical

solution to deal with the accompanying bugs that such productive fields attracted

once the application of chemicals fertilizers enhanced the growth of vegetation

on the muck bottom acres. The dikes had kept the water off of the old lake bed

where the organic peat soil called muck had rendered farming possible once sluice

gates, drainage ditches, and irrigation systems were engineered to apply the

abundant water from the partially spring-fed lake onto the surrounding vegetable

fields precisely during the dry season when climate had conspired to make Florida

a source of winter vegetables for the nation. The entire setup was a triumph

of the will to overcome natural conditions, enhance the elements that could

sustain crops and employ people on the land, in the packing houses and even

in the chemical industry. The future for all involved was brighter than a summer's

sun reflecting off the often placidly glass surface of this shallow lake, among

the largest in Florida. Ample water, even in cyclical drought times, was pumped

from the lake onto the fields where herbicides, pesticides, and fungicides were

used to enhance the yield. But it is in the application of those ingredients

that the sinister, slow but relentless process began and it started simultaneously

in the bodies of the field hands exposed to the spraying and crop dusting in

fields and in the soil across which the water silently filtered surreptitiously

moving back to the lake under the unrelenting force of gravity, carrying with

it DDT, toxephene, deildrin, and chlordane.

The solution to such a rapid loss of soil, so good for growing vegetables,

was a technical application to adjust what engineering could not forestall.

With the application of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers and herbicides to

kill the perennial weeds production was maintained. It became only another technical

solution to deal with the accompanying bugs that such productive fields attracted

once the application of chemicals fertilizers enhanced the growth of vegetation

on the muck bottom acres. The dikes had kept the water off of the old lake bed

where the organic peat soil called muck had rendered farming possible once sluice

gates, drainage ditches, and irrigation systems were engineered to apply the

abundant water from the partially spring-fed lake onto the surrounding vegetable

fields precisely during the dry season when climate had conspired to make Florida

a source of winter vegetables for the nation. The entire setup was a triumph

of the will to overcome natural conditions, enhance the elements that could

sustain crops and employ people on the land, in the packing houses and even

in the chemical industry. The future for all involved was brighter than a summer's

sun reflecting off the often placidly glass surface of this shallow lake, among

the largest in Florida. Ample water, even in cyclical drought times, was pumped

from the lake onto the fields where herbicides, pesticides, and fungicides were

used to enhance the yield. But it is in the application of those ingredients

that the sinister, slow but relentless process began and it started simultaneously

in the bodies of the field hands exposed to the spraying and crop dusting in

fields and in the soil across which the water silently filtered surreptitiously

moving back to the lake under the unrelenting force of gravity, carrying with

it DDT, toxephene, deildrin, and chlordane.

The toxic cool-aid that was intended to kill insects indiscriminately regardless

of their niche in the lakeside  ecosystem meant that the birds and the fish that

ate the insects were exposed to a contaminated cocktail of unknown proportions.

For the people working beside the lake, fixing the chemicals to load onto crop

dusters and standing under the wet sprays of the planes, the pesticide containers

made handing receptacles to use at home to store bulk wheat, rice, or cereal

to feed the family or buckets in which to wash the clothes. In an macabre facet

of reuse of materials the propensity of the field workers to recycle the empty

containers would by the 1980s expose them further to enough endocrine disrupting,

cancer provoking, and astringent compounds to kill if not disable. What was

slowly undermining the health of the farm workers was insidiously manifest in

the lake's creatures. Once the premier bass fishery in the south east, surrounded

by fish camps of economic importance to the wealth of the community, Lake Apopka

in little more than twenty years was turned into a green algal dominated water

system where fish struggled with bacteria for oxygen as more wetlands were removed

from the shoreline. The promise of agrarian abundance beside an inland --freshwater--

sea with the highest bird diversity counts by Florida Audubon seen anywhere

in the state was rendering the the water "undrinkable, unswimmable, and unfishable."

ecosystem meant that the birds and the fish that

ate the insects were exposed to a contaminated cocktail of unknown proportions.

For the people working beside the lake, fixing the chemicals to load onto crop

dusters and standing under the wet sprays of the planes, the pesticide containers

made handing receptacles to use at home to store bulk wheat, rice, or cereal

to feed the family or buckets in which to wash the clothes. In an macabre facet

of reuse of materials the propensity of the field workers to recycle the empty

containers would by the 1980s expose them further to enough endocrine disrupting,

cancer provoking, and astringent compounds to kill if not disable. What was

slowly undermining the health of the farm workers was insidiously manifest in

the lake's creatures. Once the premier bass fishery in the south east, surrounded

by fish camps of economic importance to the wealth of the community, Lake Apopka

in little more than twenty years was turned into a green algal dominated water

system where fish struggled with bacteria for oxygen as more wetlands were removed

from the shoreline. The promise of agrarian abundance beside an inland --freshwater--

sea with the highest bird diversity counts by Florida Audubon seen anywhere

in the state was rendering the the water "undrinkable, unswimmable, and unfishable."

But if you did not know any better the deceptive size of the lake, the engineered

abundance of its orchards and fields and the growing prosperity of its landlords

could be mistaken for progress. The slowly ticking time bomb of endocrine mimicry,

carcinogens, and ultraviolet radiation was accumulating in the bodies of the

farm workers, the resistant insects in the fields, the fish that fed on the

biocide filled insects and the birds that feasted in the shallows on the fish

that imbibed in the toxic cocktail that had become public property.

There are more ironies in the story of the people of the lake than any drama

or tragicomedy deserves to have, more than anyone can think about and still

remain sober. Its as if the intoxicant of too many ironies leads to an inevitable

question: "What in sweet God's name had happened to this garden in the

grasslands of central Florida?"

The lake had, by law always been public

property, the waters governed by navigational priorities of the federal Army

Corps of Engineers had been moved via a canal to a chain of lakes down the valley.

And the lake bottoms by old, if not arcane, legal custom called the public trust

doctrine were held in trust by the states – here too the State of Florida,

for the benefit of all the people to hunt and to fish. The farm workers and

other local residents still fish in the Lake for largemouth bass, bluegill,

shellcracker and sunshine bass as they had for generations because it is after

all a cheap source of protein. Except that to control the growth of aquatic

weeds in the lake once it began to be fed extra doses of fertilizer from the

vegetable fields and fruit orchards, gizzard shad were introduced to this mix

of sport and food fish.

The 30,672 acres that remained of the lake surface after

the drainage and decking of the north shore fields was home to alligators and

turtles, wading birds like great blue herons immortalized in painting by John

James Audubon as the Louisiana heron, and countless ibis, cranes, egrets and

even sea gulls. But it is the ducks, if there were any wetlands left that could

amaze the most practiced hunter. Ducks by the drove over-winter here where the

shallow water fed by a spring from the Floridan aquifer, conspire with the sun

and the marshes of the lakeshore to produce an alchemy of abundance, so long

as the water is clean. The water here is public, the waters gifts or bounty

be it in fish, birds, or crops through a peculiar process of ownership become

private property to those who possess the industry, determination and perseverance

to harvest these public resources.

But if Eden ever possessed a lake this one

would be a great descendant of that fabled lake and Lake Apopka is surely the

source of this garden of the knowledge of good and evil. Beside its waters generations

of field hands baptized their children, even the still borne and the birth defect

children that began to show the tell tale signs of exposure to poisons used

to wring a better, hardier crop from the land.

Because of the indiscriminate character of the herbicides, fungicides, and

pesticides used in modern agricultural production, Garrett Hardin, human ecologist

and algal specialist once called these treatments biocides. He argued that,

like antibiotics prevalent in medical therapy for infections, the use of poisons

to control pests are lethal to all living things, not just the rapidly producing

insects, frogs, or algae. In a sort of queer irony of Darwinian selection the

very pests we seek to control by killing the reproductive parents leave behind

drug and poison resistant descendants who live to reproduce and instill their

resistance to another, ever hardier generation. The irony is lost on folks here

because, in part they do not want their children to learn about Darwin and evolution

for fear they will lose their faith in the creator God. But one consequence

of the agrarian dream for the people of the Lake was that as Betty Dubois experienced

miscarriages and her children grew with learning disabilities the insidious

quality of degraded water quality was becoming all too apparent to fisherman

long before a chemical spill near the Gourd neck spring that feeds the lake

dumped pesticides directly into the southern part of the system. That attracted

attention, but not near the focus that Gainesville based biologists at the University

of Florida brought when in the mid 1980s they published their findings that

alligators, male alligators at that, found in that area of the lake were born

with misshapen genitalia – so stunted they could not reproduce.

The alligators,

symbol of the state's premiere research university, were, well less male than

could win them a place in the struggle to reproduce. It was as if the ghost

of Charles Darwin was ridiculing the entire agrarian dream of southern landowners

by interfering with--not only the pests they were breeding in the fields--but

in the very reproductive systems that reptiles, mammals and humans share. While

many will dispute the hard evidence that the spontaneous abortions and still

birth occurrences among farm worker women have little or nothing to do with

exposure to manufactured chemicals used to enhance the productivity of the fields

that were hauled up out of the Lake's muck bottom, the the toxins stored in

the soils and plants of the lake are held in the fat tissue of the fish and

wildlife and reside in the bodies of the field hands who from these "phosphate

fed fields feed" us today. This is the hardest irony we take away when

staring into the opaquely green waters of this inland sea and that is the paradox

that we have let progress stand in our way of recognizing and responding effectively

to human suffering while we have all too readily responded with financial incentives

to stop the harm to fish and birds. In the pursuit of an agrarian dream of cheap

food for all based on chemicals to enhance agronomic productivity we are interfering

with our biological reproduction.

The ultimate irony is that the industrialized garden in our grasslands and

lakeshores ignited a conflagration we are ill equipped to put out because we

are busy arguing over its causes, unable to legally trace its origins from the

source to the exposed ovaries and testes of workers, and convinced that cheaply

produced food is good food. While we have the best harvest money can by the

irony growing in the fields of Lake Apopka like so many agricultural heartlands

of the country is that the public waters have borne the intoxicants right into

the food we eat by way of the bodies of the farm workers hands who inexpensively

delivered that food from the ground to trucks to our tables. By the mid 1990s

the water quality decline in the entire state was too obvious to ignore, but

Lake Apopka was like the plagues of Egypt, except for the fact that the babies

were born to farmworkers and not the Pharaohs of this land. When scientists

and technicians measured the phosphorus content in the lake from agricultural

practices and storm water runoff the 200 parts per million figure, three time

the background levels were hard for even southern politicians to ignore, though

they had tried.

In 1996 the Governor and legislature concocted a credible scheme

by which to buy back the drained lands where large landholders now grew crops

that polluted the lake and its people. In the genius of free-enterprise based

thinking, bonded and other public tax funds would be used to buy back the the

very land reclaimed from the public waters of this lake in 1941 so that the

wetlands could be restored and the natural flow of water into the lake could

again be filtered by the reeds and the marshes that for thousands of years sustained

the site of the most diverse bird counts in Florida. The cleaner water could

restore the bass fishery, the private land-holdings would be compensated at

the fair market value of their reclaimed lands, and engineers even suggested

water could be pumped from the lake -- through a reconstructed marsh to mend

the degraded, phosphorus laden, waters of the lake that was harming the public's

fish and wildlife. No more glaring omission was obvious to one newspaper reporter,

Kevin Spear, who asked the simple, annoying and deeply disturbing question,

of "what about the people who toiled in the fields for forty years and were now

without a place to work?"

Laden with the biocides that were soon to turn a lovely buy-back, or bail out

plan into a bitter and bewildering wake-up call,the farm workers had no where

to go, no health insurance, not covered by social security and without legal

representation in this negotiated settlement of the muck that once was fed by

the lake but was now eating the very sources upon which the economic and the

biological community thrived. Without work perhaps the migrants would go away,

thought some. Others realized that like the poison laden fish and alligators

the flesh and bones of these field hands were also imprinted by the persistent

organic pollutants (pop's) used to make the whole reclamation scheme in the sun show

a profit. That profit was now embodied in the increase in value of the farm

land which the state began to purchase to restore the water quality, but not

the spiritual quality or even the health of the people of the lake.

Considering the cloaked lethal conditions of these shallow waters, the wake-up

call came with the hasty re-flooding of the farm lands when the winter birds were returning to the shores. These were farms where heavy pesticides had

been used and loaded onto crop dusters after mixing the poisons. Unknown to the restoration experts the pesticides and herbicides where waiting in the dry muck soils of the newly purchased lands designed to restore the filtration of the lake and bring it back to health. So many crop

dusters flew from this area that the men who later perpetrated the 9-11 attack

on the United States sought training to fly planes in the fields north of Lake

Apopka. The re-flooded fields lay in wait for the migrating winter birds that

would be attracted to a new range of opportunity to gorge of the fish and many

invertebrates that feast on the sun fed plant supervised alchemy of water, light

and nutrients. From all outward appearances the marshes, like the people of

the lake were healthy from living the good life in the fresh air of the natural

outdoors. But that week in winter thousands of birds having eaten and eaten

well were found dead; wading birds, gulls, ducks all died.

Struggling in the death throes from eating toxic food, the greatest mass

mortality of birds in the state's horrible history of wildlife torture and decline

shocked even stone sober preachers. In the quiet agony of these dying birds

also died the hopes of restoration on the cheap. But hidden by the blare of this

news only a minority asked a more insidious question. If the inter-sexed alligators

indicated that the pesticides could interrupt reproduction and development and

if the dead birds and fish indicated that the biocides killed the exposed and

the vulnerable, then what of Betty Dubois children, or Geraldean Matthew's failing

kidneys, arthritis and thyroid problems? The final fatal irony of the people

of the lake is that you cannot see them though you eat the cabbages they pick

in the coleslaw that you consume with your next barbecue.

Here beside the water's

blue, opaque to the rays of the eternally rising and setting sun, home of the

largemouth bass and now ringed with sprawling suburban development and plans

for "smart growth," is a lakeshore where two landfills, a medical

waste incinerator, and two superfund sites bury more than just our hopes of

restoring a lake. Buried too in the graveyards of Apopka are the children of

farm workers whose parents – like the rest of us – merely sought to give a better

life to their descendants. Because money grows on trees and in fields and in

tourist lodges and fish camps these migrants came to the shores of a prosperous

experiment, only to discover they are and remain the casualties in the relentless

war of humans against an uncaring nature. Their neighbors and children are the

mortalities in this war against the microbes and the insects of these wetlands

where hope and honesty mingles with scandal and dishonesty like the ebbing and

flooding waters amidst the life restoring reeds. The children of these fields

have paid the costs of agrarian transformation, federal innovation, and industrial

agriculture with the last full measure of their lives, or with chronic illness

or recurrent learning disabilities for which modern science and technology have

yet to provide us answers.

In the artificial selection that has been practiced and is still pursued now

to restore this ailing inland sea, there are enough ironies to intoxicate the

mind for generations to come. But the continuing paradox remains of how the

best of intentions of three generations from reclamation, to agricultural prosperity,

to wetland restoration continue to stop us from seeing the people of the lake.

The people of the lake are cohabitants in our story of pain and promise, still asking for some authority

to take responsibility, and still wondering how so many, who have so much, can

do so little for those who have given the last full measure of their devotion

to their jobs. The 300,000 farm workers of Florida, like this microcosm of Lake

Apopka are living testimony of their will to survive despite a sacrifice of

their health and their children for the sake of the inexpensive food that fuels

our fast food nation.

April, 2009 & September, 2011.

Matthew said so directly,

"We fed America all our life." Born in Belle Glade, Florida the Matthew's

family moved two-hundred miles north to the citrus orchards and vegetable fields of Lake Apopka in the

upper Ocklawaha River Valley in the early 1960s because of the lure of orange

and grapefruit picking that could bring in "good money." When compared

to the sugar and tomato fields of South Florida, the conditions for stoop labor and orchard harvesting seemed to be a step out of despair.

Matthew said so directly,

"We fed America all our life." Born in Belle Glade, Florida the Matthew's

family moved two-hundred miles north to the citrus orchards and vegetable fields of Lake Apopka in the

upper Ocklawaha River Valley in the early 1960s because of the lure of orange

and grapefruit picking that could bring in "good money." When compared

to the sugar and tomato fields of South Florida, the conditions for stoop labor and orchard harvesting seemed to be a step out of despair.  The solution to such a rapid loss of soil, so good for growing vegetables,

was a technical application to adjust what engineering could not forestall.

With the application of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers and herbicides to

kill the perennial weeds production was maintained. It became only another technical

solution to deal with the accompanying bugs that such productive fields attracted

once the application of chemicals fertilizers enhanced the growth of vegetation

on the muck bottom acres. The dikes had kept the water off of the old lake bed

where the organic peat soil called muck had rendered farming possible once sluice

gates, drainage ditches, and irrigation systems were engineered to apply the

abundant water from the partially spring-fed lake onto the surrounding vegetable

fields precisely during the dry season when climate had conspired to make Florida

a source of winter vegetables for the nation. The entire setup was a triumph

of the will to overcome natural conditions, enhance the elements that could

sustain crops and employ people on the land, in the packing houses and even

in the chemical industry. The future for all involved was brighter than a summer's

sun reflecting off the often placidly glass surface of this shallow lake, among

the largest in Florida. Ample water, even in cyclical drought times, was pumped

from the lake onto the fields where herbicides, pesticides, and fungicides were

used to enhance the yield. But it is in the application of those ingredients

that the sinister, slow but relentless process began and it started simultaneously

in the bodies of the field hands exposed to the spraying and crop dusting in

fields and in the soil across which the water silently filtered surreptitiously

moving back to the lake under the unrelenting force of gravity, carrying with

it DDT, toxephene, deildrin, and chlordane.

The solution to such a rapid loss of soil, so good for growing vegetables,

was a technical application to adjust what engineering could not forestall.

With the application of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers and herbicides to

kill the perennial weeds production was maintained. It became only another technical

solution to deal with the accompanying bugs that such productive fields attracted

once the application of chemicals fertilizers enhanced the growth of vegetation

on the muck bottom acres. The dikes had kept the water off of the old lake bed

where the organic peat soil called muck had rendered farming possible once sluice

gates, drainage ditches, and irrigation systems were engineered to apply the

abundant water from the partially spring-fed lake onto the surrounding vegetable

fields precisely during the dry season when climate had conspired to make Florida

a source of winter vegetables for the nation. The entire setup was a triumph

of the will to overcome natural conditions, enhance the elements that could

sustain crops and employ people on the land, in the packing houses and even

in the chemical industry. The future for all involved was brighter than a summer's

sun reflecting off the often placidly glass surface of this shallow lake, among

the largest in Florida. Ample water, even in cyclical drought times, was pumped

from the lake onto the fields where herbicides, pesticides, and fungicides were

used to enhance the yield. But it is in the application of those ingredients

that the sinister, slow but relentless process began and it started simultaneously

in the bodies of the field hands exposed to the spraying and crop dusting in

fields and in the soil across which the water silently filtered surreptitiously

moving back to the lake under the unrelenting force of gravity, carrying with

it DDT, toxephene, deildrin, and chlordane. ecosystem meant that the birds and the fish that

ate the insects were exposed to a contaminated cocktail of unknown proportions.

For the people working beside the lake, fixing the chemicals to load onto crop

dusters and standing under the wet sprays of the planes, the pesticide containers

made handing receptacles to use at home to store bulk wheat, rice, or cereal

to feed the family or buckets in which to wash the clothes. In an macabre facet

of reuse of materials the propensity of the field workers to recycle the empty

containers would by the 1980s expose them further to enough endocrine disrupting,

cancer provoking, and astringent compounds to kill if not disable. What was

slowly undermining the health of the farm workers was insidiously manifest in

the lake's creatures. Once the premier bass fishery in the south east, surrounded

by fish camps of economic importance to the wealth of the community, Lake Apopka

in little more than twenty years was turned into a green algal dominated water

system where fish struggled with bacteria for oxygen as more wetlands were removed

from the shoreline. The promise of agrarian abundance beside an inland --freshwater--

sea with the highest bird diversity counts by Florida Audubon seen anywhere

in the state was rendering the the water "undrinkable, unswimmable, and unfishable."

ecosystem meant that the birds and the fish that

ate the insects were exposed to a contaminated cocktail of unknown proportions.

For the people working beside the lake, fixing the chemicals to load onto crop

dusters and standing under the wet sprays of the planes, the pesticide containers

made handing receptacles to use at home to store bulk wheat, rice, or cereal

to feed the family or buckets in which to wash the clothes. In an macabre facet

of reuse of materials the propensity of the field workers to recycle the empty

containers would by the 1980s expose them further to enough endocrine disrupting,

cancer provoking, and astringent compounds to kill if not disable. What was

slowly undermining the health of the farm workers was insidiously manifest in

the lake's creatures. Once the premier bass fishery in the south east, surrounded

by fish camps of economic importance to the wealth of the community, Lake Apopka

in little more than twenty years was turned into a green algal dominated water

system where fish struggled with bacteria for oxygen as more wetlands were removed

from the shoreline. The promise of agrarian abundance beside an inland --freshwater--

sea with the highest bird diversity counts by Florida Audubon seen anywhere

in the state was rendering the the water "undrinkable, unswimmable, and unfishable."