“Accounting for Environmental Assets,”

Robert Repetto

Scientific American, June 1992, pp. 94 - 100.

§§§

“Impoverishment is taken for progress.”

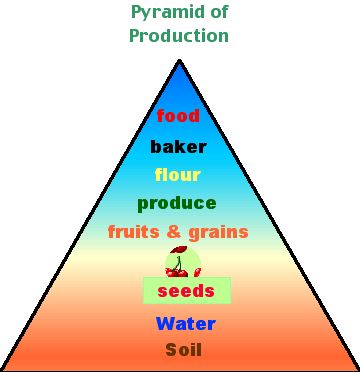

A model of the foundations of wealth from an ecological perspective.

There is a problem with the UN System of National Accounts (SNA)

“completely ignores the crucial environmental changes of our times: the

marked degradation of natural resources in much of the the developing world

and the growing pressures on global life support systems such as climate and

biological diversity.

“By failing to recognize the asset value of natural resources, the accounting

framework that underlies the principle tools of economic analysis misrepresents

the policy choices nations face.”

Impact of Externalities debit credit earth capital legend: >, increase of; <, decrease of

“Keynesian analysis for the most part ignored the productive role of

natural resources, so does the current system of national accounts.”

(94)

“there is a dangerous asymmetry in the way economists measure, and hence the way they think about the value of natural resources.”

“Buildings, equipment and other manufactured assets are valued as income producing capital, and their depreciation is written off as a charge against the value of production. This practice recognizes that consumption cannot be maintained indefinitely simply by drawing down the stock of capital without replenishing it. Natural resource assets, however, are not so valued. Their loss, even though it may lead to a significant decrease in future production, entails no charge against current income.” (96)

--Page 1--

“Although the model balance sheet in the U.N. SNA recognizes

land, minerals, and timber as economic assets to be included in a nation’s

capital stock, the SNA income and product accounts do not.” (96)

“Ironically, low-income countries, which are typically most dependent on

natural resources for employment, revenues and foreign exchange earnings, are

instructed to use a national accounting system that almost completely ignores

their principle assets.”

“Behind this anomaly is the mistaken assumption that natural resources

are so abundant that they have no marginal value.”

“Another misunderstanding is that natural resources are ‘free gifts

of nature,’ so that there are no investment costs to be written off per

se. The value of an asset, however, is not its investment cost but the present

value of its income potential.”

“The true measure of depreciation is the capitalized present value of the

reduction in future income from the asset because of its decay or obsolescence.

In the same way that a machine depreciates as it wears out, soils depreciate

as their fertility is diminished, since they can produce the same crop yield

only at higher cost.” (96)

“One of the hemisphere’s highest rates of deforestation (Costa Rica)

has led to the loss of 30% of the country’s forests. Furthermore, most

of the forest was simply burned to clear land for relatively unproductive pastures

and hill farms, sacrificing both valuable tropical timber and myriad plant,

animal and insect species. Because most of the area converted from forest was

unusable for agriculture, its soil eroded in torrents. Losses averaged more

than 300 tons per hectare from land use to grow annual crops and nearly 50 tons

per hectare from pastures.” (96-97)

“Because forests, fisheries, farming and mining directly account for 17

percent of Costa Rica’s national income, 25 percent of its employment and

55% of its export earnings, this destruction caused severe economic losses . . . . Yet

nothing in Costa Rica’s national economic accounts records these economic

losses.” (97)

“Because forests, fisheries, farming and mining directly account for 17

percent of Costa Rica’s national income, 25 percent of its employment and

55% of its export earnings, this destruction caused severe economic losses . . . . Yet

nothing in Costa Rica’s national economic accounts records these economic

losses.” (97)

“The experience of other developing countries for which natural resource

accounts have been compiled parallels that of Costa Rica. In the Philippines,

for example, annual losses resulting from deforestation averaged 3.3 percent

of the GDP between 1970 and 1987....This pollution, together with overfishing,

wiped out all profits by 1984. Although the nation’s accounts showed a

mounting external debt, they gave no sign of destruction in productive capacity

that made paying back that debt more unlikely.” (98)

“Indonesia’s natural resource accounts show that between 1977 and

1984 the depletion of natural resources totaled 19 percent of GDP.... Once again, conventional accounting methods show no sign of this impending danger.”

(100)

- Page 2-

![]()

Scientific American, June 1992, pp. 94 - 100.