An instrument to interpret the "Will of Heaven."

Su Sung's clock

As a result of this the Emperor Shen Tsung in about 1100 AD decided to build the most perfect clock the world had ever seen. He assigned the task to his minister Su Sung who, after several years, came up with a water-powered clock that not only told the time of day, but the date, month and a host of other things as well.

In fact, Su Sung's clock ran from 1092 until 1126 when the capital, K'aifeng, was lost by the Sung Dynasty. The clock was then dismantled, moved to Peking, and reassembled there, where it ran for some years further. The clock had previous vicissitudes which shed light upon the spirit of the times. Members of political factions opposed to the one of which Su Sung had been a member (he was a conservative) wanted to destroy his clock for political reasons. We are told this by Chu Pien in his book Talks about Bygone Things beside the Winding Wei (river in Honan) of 1140:

In fact, Su Sung's clock ran from 1092 until 1126 when the capital, K'aifeng, was lost by the Sung Dynasty. The clock was then dismantled, moved to Peking, and reassembled there, where it ran for some years further. The clock had previous vicissitudes which shed light upon the spirit of the times. Members of political factions opposed to the one of which Su Sung had been a member (he was a conservative) wanted to destroy his clock for political reasons. We are told this by Chu Pien in his book Talks about Bygone Things beside the Winding Wei (river in Honan) of 1140:

But at the beginning of the Shao-Sheng reign-period [1094 AD] Ts'ai Pien, Minister of State, suggested that the armiflary clock of Su Sung ought to be destroyed as something which belonged to the previous Yuan-Yu reign period [of only two years before]. At that time Ch'ao Mei-Shu was Assistant Director of the Imperial Library, and as he greatly admired the accuracy and beautiful construction of Su Sung's instruments, he struggled to argue against Ts'ai Pien, but at first his efforts proved unsuccessful.

Su Sung's clock was possibly the greatest mechanical achievement of the Middle Ages anywhere on the globe (for further details of its working see pictures and captions accompanying this text), and knowledge of its principles spreading to Europe led to the development of mechanical clocks in the West two centuries later.

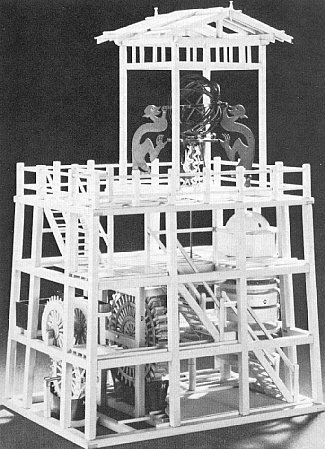

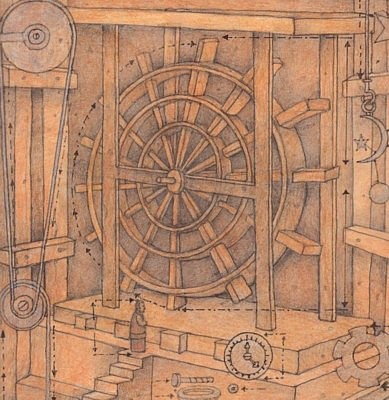

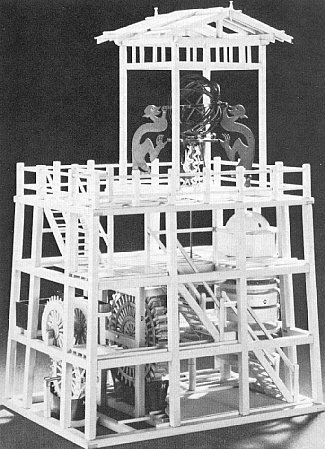

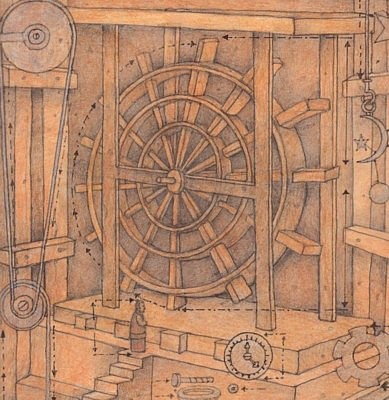

A model of the 'Cosmic Engine', Su Sung's great astronomical clock of 1092. The framework has been left uncovered to reveal the mechanisms. The original clock tower was 30 feet high. At the top is the power-driven armillary sphere for observing the positions of the stars. In the original, this was bronze, and the power for turning it was transmitted by a chain- drive. Mid-right (B) may be seen a celestial globe which was inside the tower and turned in synchronization with the sphere above. The central element in the reconstruction (D) is the water-wheel escapement, which, though turned by water power, was a mechanical escapement. This was a mechanical clock rather than a water clock, even though its power came from failing water or mercury. (Science Museum, London.)

A model of the 'Cosmic Engine', Su Sung's great astronomical clock of 1092. The framework has been left uncovered to reveal the mechanisms. The original clock tower was 30 feet high. At the top is the power-driven armillary sphere for observing the positions of the stars. In the original, this was bronze, and the power for turning it was transmitted by a chain- drive. Mid-right (B) may be seen a celestial globe which was inside the tower and turned in synchronization with the sphere above. The central element in the reconstruction (D) is the water-wheel escapement, which, though turned by water power, was a mechanical escapement. This was a mechanical clock rather than a water clock, even though its power came from failing water or mercury. (Science Museum, London.)

The Chinese did not invent the first clock of any kind, merely the first mechanical one. Water clocks had existed since Babylonian times, and the earliest Chinese got them indirectly from that earlier civilization of the Middle East, just as they got much of their earliest forms of astronomy from them. The Chinese certainly did invent improved water clocks of various kinds, including a 'stop-watch' portable one which used mercury rather than water and measured small periods of time. It used weighted balances, or steelyards, rather than just a rising indicator in a bucket as water flowed in and buoyed it up. But these were improvements of an invention which was not originally Chinese. Nor did the Chinese invent the clock dial. That was an invention of either the Greeks or the Romans, and is mentioned by the architectural writer Vitruvius in the first century BC.

Su-Sung's clock was stolen when invading Tatars put an end to the Sung dynasty in 1126. The Tatars weren't able to get it running again, and the high art of Chinese clock-making completely disappeared. But even before the Tatar invasion, Taoistic reformers had come into power. They saw fancy clock-building as part of the older regime and did little to sustain it. Su-Sung's book on the operation of his clock didn't surface in the West until the 17th century.

Fine technology

Technology in the distant past

http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi120.htm

In fact, Su Sung's clock ran from 1092 until 1126 when the capital, K'aifeng, was lost by the Sung Dynasty. The clock was then dismantled, moved to Peking, and reassembled there, where it ran for some years further. The clock had previous vicissitudes which shed light upon the spirit of the times. Members of political factions opposed to the one of which Su Sung had been a member (he was a conservative) wanted to destroy his clock for political reasons. We are told this by Chu Pien in his book Talks about Bygone Things beside the Winding Wei (river in Honan) of 1140:

In fact, Su Sung's clock ran from 1092 until 1126 when the capital, K'aifeng, was lost by the Sung Dynasty. The clock was then dismantled, moved to Peking, and reassembled there, where it ran for some years further. The clock had previous vicissitudes which shed light upon the spirit of the times. Members of political factions opposed to the one of which Su Sung had been a member (he was a conservative) wanted to destroy his clock for political reasons. We are told this by Chu Pien in his book Talks about Bygone Things beside the Winding Wei (river in Honan) of 1140: A model of the 'Cosmic Engine', Su Sung's great astronomical clock of 1092. The framework has been left uncovered to reveal the mechanisms. The original clock tower was 30 feet high. At the top is the power-driven armillary sphere for observing the positions of the stars. In the original, this was bronze, and the power for turning it was transmitted by a chain- drive. Mid-right (B) may be seen a celestial globe which was inside the tower and turned in synchronization with the sphere above. The central element in the reconstruction (D) is the water-wheel escapement, which, though turned by water power, was a mechanical escapement. This was a mechanical clock rather than a water clock, even though its power came from failing water or mercury. (Science Museum, London.)

A model of the 'Cosmic Engine', Su Sung's great astronomical clock of 1092. The framework has been left uncovered to reveal the mechanisms. The original clock tower was 30 feet high. At the top is the power-driven armillary sphere for observing the positions of the stars. In the original, this was bronze, and the power for turning it was transmitted by a chain- drive. Mid-right (B) may be seen a celestial globe which was inside the tower and turned in synchronization with the sphere above. The central element in the reconstruction (D) is the water-wheel escapement, which, though turned by water power, was a mechanical escapement. This was a mechanical clock rather than a water clock, even though its power came from failing water or mercury. (Science Museum, London.)