Willa Cather,

Death Comes for the Archbishop

1927.

Who | Where | What | How | Allusions

Willa Cather may be among the nations most gifted fiction writers.

Willa Cather [December 7, 1873 – April 24, 1947] moved from Virginia to the Nebraska frontier as a child. Her passionate love for the land and the sky was born beneath these immense skies of Nebraska.

George Catlin's Missouri River.

George Catlin's Missouri River.

Cather wrote poetry, essays, and many novels, achieving both critical and popular success, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1923.

She died in 1947 in New York City and was buried in New Hampshire. Engraved on her tombstone is a quote from her book My Antonia: “… that is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great.”

The candidate for the Archbishop of New Mexico

PROLOGUE: AT ROME

"Where is your candidate at present, Father?"

"He is a parish priest, on the shores of Lake Ontario, in my diocese. I have watched his work for nine years. He is but thirty-five now. He came to us directly from the Seminary."

"And his name is?"

"Jean Marie Latour."

Chapter One: The Cruciform Tree

One afternoon in the autumn of 1851 a solitary horseman, followed by a pack-mule, was pushing through an arid stretch of country somewhere in central New Mexico. He had lost his way, and was trying to get back to the trail, with only his compass and his sense of direction for guides. The difficulty was that the country in which he found himself was so featureless--or rather, that it was crowded with features, all exactly alike. As far as he could see, on every side, the landscape was heaped up into monotonous red sand-hills, not much larger than haycocks, and very much the shape of haycocks. One could not have believed that in the number of square miles a man is able to sweep with the eye there could be so many uniform red hills. He had been riding among them since early morning, and the look of the country had no more changed than if he had stood still. He must have travelled through thirty miles of these conical red hills, winding his way in the narrow cracks between them, and he had begun to think that he would never see anything else.

They were so exactly like one another that he seemed to be wandering in some geometrical nightmare; flattened cones, they were, more the shape of Mexican ovens than haycocks-- yes, exactly the shape of Mexican ovens, red as brick-dust, and naked of vegetation except for small juniper trees. And the junipers, too, were the shape of Mexican ovens. Every conical hill was spotted with smaller cones of juniper, a uniform yellowish green, as the hills were a uniform red. The hills thrust out of the ground so thickly that they seemed to be pushing each other, elbowing each other aside, tipping each other over. The blunted pyramid, repeated so many hundred times upon his retina and crowding down upon him in the heat, had confused the traveller, who was sensitive to the shape of things.

"Mais, c'est fantastique!" he muttered, closing his eyes to rest them from the intrusive omnipresence of the triangle. When he opened his eyes again, his glance immediately fell upon one juniper which differed in shape from the others. It was not a thick-growing cone, but a naked, twisted trunk, perhaps ten feet high, and at the top it parted into two lateral, flat-lying branches, with a little crest of green in the centre, just above the cleavage. Living vegetation could not present more faithfully the form of the Cross.

The traveller dismounted, drew from his pocket a much worn book, and baring his head, knelt at the foot of the cruciform tree.

. . . .

He had been warned that there were many trails leading off the Rio Grande road, and that a stranger might easily mistake his way. For the first few days he had been cautious and watchful. Then he must have grown careless and turned into some purely local trail. When he realized that he was astray, his canteen was already empty and his horses seemed too exhausted to retrace their steps. He had persevered in this sandy track, which grew ever fainter, reasoning that it must lead somewhere.

All at once Father Latour thought he felt a change in the body of his mare. She lifted her head for the first time in a long while, and seemed to redistribute her weight upon her legs. The pack-mule behaved in a similar manner, and both quickened their pace. Was it possible they scented water? Nearly an hour went by, and then, winding between two hills that were like all the hundreds they had passed, the two beasts whinnied simultaneously.

Below them, in the midst of that wavy ocean of sand, was a green thread of verdure and a running stream. This ribbon in the desert seemed no wider than a man could throw a stone,--and it was greener than anything Latour had ever seen, even in his own greenest corner of the Old World. But for the quivering of the hide on his mare's neck and shoulders, he might have thought this a vision, a delusion of thirst.

Running water, clover fields, cottonwoods, acacias, little adobe houses with brilliant gardens, a boy driving a flock of white goats toward the stream,--that was what the young Bishop saw. A few moments later, when he was struggling with his horses, trying to keep them from overdrinking, a young girl with a black shawl over her head came running toward him. He thought he had never seen a kindlier face.

Book Four: Snake Root

Chapter 2: The Night at Pecos

"Cradles were not many in the pueblo of Pecos. The tribe was dying out; infant mortality was heavy, and the young couples did not reproduce freely, – the life force seemed low Smallpox and measles had taken heavy toll here time and again."

Of course there were other explanations, credited by many good people in Santa Fe. Pecos had more than its share of dark legends,--perhaps that was because it had been too tempting to white men, and had had more than its share of history. It was said that this people had from time immemorial kept a ceremonial fire burning in some cave in the mountain, a fire that had never been allowed to go out, and had never been revealed to white men. The story was that the service of this fire sapped the strength of the young men appointed to serve it, -- always the best of the tribe. Father Latour thought this hardly probable. Why should it be very arduous, in a mountain full of timber, to feed a fire so small that its whereabouts had been concealed for centuries?

There was also the snake story, reported by the early explorers, both Spanish and American, and believed ever since: that this tribe was peculiarly addicted to snake worship, that they kept rattlesnakes concealed in their houses, and somewhere in the mountain guarded an enormous serpent which they brought to the pueblo for certain feasts. It was said that they sacrificed young babies to the great snake, and thus diminished their numbers.

It seemed much more likely that the contagious diseases brought by white men were the real cause of the shrinkage of the tribe. Among the Indians, measles, scarlatina and whooping-cough were as deadly as typhus or cholera. Certainly, the tribe was decreasing every year. Jacinto's house was at one end of the living pueblo; behind it were long rock ridges of dead pueblo,--empty houses ruined by weather and now scarcely more than piles of earth and stone. The population of the living streets was less than one hundred adults.* This was all that was left of the rich and populous Cicuy of Coronado's expedition. Then, by his report, there were six thousand souls in the Indian town. They had rich fields irrigated from the Pecos River. The streams were full of fish, the mountain was full of game. The pueblo, indeed, seemed to lie upon the knees of these verdant mountains, like a favoured child. Out yonder, on the juniper-spotted plateau in front of the village, the Spaniards had camped, exacting a heavy tribute of corn and furs and cotton garments from their hapless hosts. It was from here, the story went, that they set forth in the spring on their ill-fated search for the seven golden cities of Quivera, taking with them slaves and concubines ravished from the Pecos people.

Chapter 2: Stone Lips

It was not difficult for the Bishop to waken early. After midnight his body became more and more chilled and cramped. He said his prayers before he rolled out of his blankets, remembering Father Vaillant's maxim that if you said your prayers first, you would find plenty of time for other things afterward.

Going through the silent pueblo to Jacinto's door, the Bishop woke him and asked him to make a fire. While the Indian went to get the mules ready, Father Latour got his coffee-pot and tin cup out of his saddle-bags, and a round loaf of Mexican bread. With bread and black coffee, he could travel day after day. Jacinto was for starting without breakfast, but Father Latour made him sit down and share his loaf. Bread is never too plenty in Indian households. Clara was still lying on the settle with her baby.

At four o'clock they were on the road, Jacinto riding the mule that carried the blankets. He knew the trails through his own mountains well enough to follow them in the dark. Toward noon the Bishop suggested a halt to rest the mules, but his guide looked at the sky and shook his head. The sun was nowhere to be seen, the air was thick and grey and smelled of snow. Very soon the snow began to fall--lightly at first, but all the while becoming heavier. The vista of pine trees ahead of them grew shorter and shorter through the vast powdering of descending flakes. A little after mid-day a burst of wind sent the snow whirling in coils about the two travellers, and a great storm broke. The wind was like a hurricane at sea, and the air became blind with snow. The Bishop could scarcely see his guide--saw only parts of him, now a head, now a shoulder, now only the black rump of his mule. Pine trees by the way stood out for a moment, then disappeared absolutely in the whirlpool of snow. Trail and landmarks, the mountain itself, were obliterated.

Jacinto sprang from his mule and unstrapped the roll of blankets. Throwing the saddle-bags to the Bishop, he shouted, "Come, I know a place. Be quick, Padre."

The Bishop protested they could not leave the mules. Jacinto said the mules must take their chance.

For Father Latour the next hour was a test of endurance. He was blind and breathless, panting through his open mouth. He clambered over half-visible rocks, fell over prostrate trees, sank into deep holes and struggled out, always following the red blankets on the shoulders of the Indian boy, which stuck out when the boy himself was lost to sight.

Suddenly the snow seemed thinner. The guide stopped short. They were standing, the Bishop made out, under an overhanging wall of rock which made a barrier against the storm. Jacinto dropped the blankets from his shoulder and seemed to be preparing to climb the cliff. Looking up, the Bishop saw a peculiar formation in the rocks; two rounded ledges, one directly over the other, with a mouth-like opening between. They suggested two great stone lips, slightly parted and thrust outward. Up to this mouth Jacinto climbed quickly by footholds well known to him. Having mounted, he lay down on the lower lip, and helped the Bishop to clamber up. He told Father Latour to wait for him on this projection while he brought up the baggage.

A few moments later the Bishop slid after Jacinto and the blankets, through the orifice, into the throat of the cave. Within stood a wooden ladder, like that used in kivas, and down this he easily made his way to the floor.

He found himself in a lofty cavern, shaped somewhat like a Gothic chapel, of vague outline,--the only light within was that which came through the narrow aperture between the stone lips. Great as was his need of shelter, the Bishop, on his way down the ladder, was struck by reluctance, an extreme distaste for the place. The air in the cave was glacial, penetrated to the very bones, and he detected at once a fetid odour, not very strong but highly disagreeable. Some twenty feet or so above his head the open mouth let in grey daylight like a high transom.

While he stood gazing about, trying to reckon the size of the cave, his guide was intensely preoccupied in making a careful examination of the floor and walls. At the foot of the ladder lay a heap of half-burned logs. There had been a fire there, and it had been extinguished with fresh earth,--a pile of dust covered what had been the heart of the fire. Against the cavern wall was a heap of piñon faggots, neatly piled. After he had made a minute examination of the floor, the guide began cautiously to move this pile of wood, taking the sticks up one by one, and putting them in another spot. The Bishop supposed he would make a fire at once, but he seemed in no haste to do so. Indeed, when he had moved the wood he sat down upon the floor and fell into reflection. Father Latour urged him to build a fire without further delay.

"Padre," said the Indian boy, "I do not know if it was right to bring you here. This place is used by my people for ceremonies and is known only to us. When you go out from here, you must forget."

"I will forget, certainly. But unless we can have a fire, we had better go back into the storm. I feel ill here already."

Jacinto unrolled the blankets and threw the dryest one about the shivering priest. Then he bent over the pile of ashes and charred wood, but what he did was to select a number of small stones that had been used to fence in the burning embers. These he gathered in his sarape and carried to the rear wall of the cavern, where, a little above his head, there seemed to be a hole. It was about as large as a very big watermelon, of an irregular oval shape.

Holes of that shape are common in the black volcanic cliffs of the Pajarito Plateau, where they occur in great numbers. This one was solitary, dark, and seemed to lead into another cavern. Though it lay higher than Jacinto's head, it was not beyond easy reach of his arms, and to the Bishop's astonishment he began deftly and noiselessly to place the stones he had collected within the mouth of this orifice, fitting them together until he had entirely closed it. He then cut wedges from the piñon faggots and inserted them into the cracks between the stones. Finally, he took a handful of the earth that had been used to smother the dead fire, and mixed it with the wet snow that had blown in between the stone lips. With this thick mud he plastered over his masonry, and smoothed it with his palm. The whole operation did not take a quarter of an hour.

Without comment or explanation he then proceeded to build a fire. The odour so disagreeable to the Bishop soon vanished before the fragrance of the burning logs. The heat seemed to purify the rank air at the same time that it took away the deathly chill, but the dizzy noise in Father Latour's head persisted. At first he thought it was a vertigo, a roaring in his ears brought on by cold and changes in his circulation. But as he grew warm and relaxed, he perceived an extraordinary vibration in this cavern; it hummed like a hive of bees, like a heavy roll of distant drums. After a time he asked Jacinto whether he, too, noticed this. The slim Indian boy smiled for the first time since they had entered the cave. He took up a faggot for a torch, and beckoned the Padre to follow him along a tunnel which ran back into the mountain, where the roof grew much lower, almost within reach of the hand. There Jacinto knelt down over a fissure in the stone floor, like a crack in china, which was plastered up with clay. Digging some of this out with his hunting knife, he put his ear on the opening, listened a few seconds, and motioned the Bishop to do likewise.

Father Latour lay with his ear to this crack for a long while, despite the cold that arose from it. He told himself he was listening to one of the oldest voices of the earth. What he heard was the sound of a great underground river, flowing through a resounding cavern. The water was far, far below, perhaps as deep as the foot of the mountain, a flood moving in utter blackness under ribs of antediluvian rock. It was not a rushing noise, but the sound of a great flood moving with majesty and power.

"It is terrible," he said at last, as he rose.

"Si, Padre." Jacinto began spitting on the clay he had gouged out of the seam, and plastered it up again.

When they returned to the fire, the patch of daylight up between the two lips had grown much paler. The Bishop saw it die with regret. He took from his saddlebags his coffee-pot and a loaf of bread and a goat cheese. Jacinto climbed up to the lower ledge of the entrance, shook a pine tree, and filled the coffee-pot and one of the blankets with fresh snow. While his guide was thus engaged, the Bishop took a swallow of old Taos whisky from his pocket flask. He never liked to drink spirits in the presence of an Indian.

Jacinto declared that he thought himself lucky to get bread and black coffee. As he handed the Bishop back his tin cup after drinking its contents, he rubbed his hand over his wide sash with a smile of pleasure that showed all his white teeth.

"We had good luck to be near here," he said. "When we leave the mules, I think I can find my way here, but I am not sure. I have not been here very many times. You was scare, Padre?"

The Bishop reflected. "You hardly gave me time to be scared, boy.

Were you?"

The Indian shrugged his shoulders. "I think not to return to pueblo," he admitted.

Father Latour read his breviary long by the light of the fire. Since early morning his mind had been on other than spiritual things. At last he felt that he could sleep. He made Jacinto repeat a Pater Noster with him, as he always did on their night camps, rolled himself in his blankets, and stretched out, feet to the fire. He had it in his mind, however, to waken in the night and study a little the curious hole his guide had so carefully closed. After he put on the mud, Jacinto had never looked in the direction of that hole again, and Father Latour, observing Indian good manners, had tried not to glance toward it.

He did waken, and the fire was still giving off a rich glow of light in that lofty Gothic chamber. But there against the wall was his guide, standing on some invisible foothold, his arms outstretched against the rock, his body flattened against it, his ear over that patch of fresh mud, listening; listening with super-sensual ear, it seemed, and he looked to be supported against the rock by the intensity of his solicitude. The Bishop closed his eyes without making a sound and wondered why he had supposed he could catch his guide asleep.

The next morning they crawled out through the stone lips, and dropped into a gleaming white world. The snow-clad mountains were red in the rising sun. The Bishop stood looking down over ridge after ridge of wintry fir trees with the tender morning breaking over them, all their branches laden with soft, rose-coloured clouds of virgin snow.

Jacinto said it would not be worthwhile to look for the mules. When the snow melted, he would recover the saddles and bridles. They floundered on foot some eight miles to a squatter's cabin, rented horses, and completed their journey by starlight. When they reached Father Vaillant, he was sitting up in a bed of buffalo skins, his fever broken, already on the way to recovery. Another good friend had reached him before the Bishop. Kit Carson, on a deer hunt in the mountains with two Taos Indians, had heard that this village was stricken and that the Vicario was there. He hurried to the rescue, and got into the pueblo with a pack of venison meat just before the storm broke. As soon as Father Vaillant could sit in the saddle, Carson and the Bishop took him back to Santa Fe, breaking the journey into four days because of his enfeebled state.

The Bishop kept his word, and never spoke of Jacinto's cave to anyone, but he did not cease from wondering about it. It flashed into his mind from time to time, and always with a shudder of repugnance quite unjustified by anything he had experienced there. It had been a hospitable shelter to him in his extremity. Yet afterward he remembered the storm itself, even his exhaustion, with a tingling sense of pleasure. But the cave, which had probably saved his life, he remembered with horror. No tales of wonder, he told himself, would ever tempt him into a cavern hereafter.

At home again, in his own house, he still felt a certain curiosity about this ceremonial cave, and Jacinto's puzzling behaviour. It seemed almost to lend a colour of probability to some of those unpleasant stories about the Pecos religion. He was already convinced that neither the white men nor the Mexicans in Santa Fe understood anything about Indian beliefs or the workings of the Indian mind.

Book Nine: Chapter Three.

The next morning Father Latour wakened with a grateful sense of nearness to his Cathedral--which would also be his tomb. He felt safe under its shadow; like a boat come back to harbour, lying under its own sea-wall. He was in his old study; the Sisters had sent a little iron bed from the school for him, and their finest linen and blankets. He felt a great content at being here, where he had come as a young man and where he had done his work. The room was little changed; the same rugs and skins on the earth floor, the same desk with his candlesticks, the same thick, wavy white walls that muted sound, that shut out the world and gave repose to the spirit. As the darkness faded into the grey of a winter morning, he listened for the church bells,--and for another sound, that always amused him here; the whistle of a locomotive. Yes, he had come with the buffalo, and he had lived to see railway trains running into Santa Fe. He had accomplished an historic period.

All his relatives at home, and his friends in New Mexico, had expected that the old Archbishop would spend his closing years in France, probably in Clermont, where he could occupy a chair in his old college. That seemed the natural thing to do, and he had given it grave consideration. He had half expected to make some such arrangement the last time he was in Auvergne, just before his retirement from his duties as Archbishop. But in the Old World he found himself homesick for the New. It was a feeling he could not explain; a feeling that old age did not weigh so heavily upon a man in New Mexico as in the Puy-de-Dome.

He loved the towering peaks of his native mountains, the comeliness of the villages, the cleanness of the country-side, the beautiful lines and cloisters of his own college. Clermont was beautiful,-- but he found himself sad there; his heart lay like a stone in his breast. There was too much past, perhaps. . . . When the summer wind stirred the lilacs in the old gardens and shook down the blooms of the horse-chestnuts, he sometimes closed his eyes and thought of the high song the wind was singing in the straight, striped pine trees up in the Navajo forests.

During the day his nostalgia wore off, and by dinner-time it was quite gone. He enjoyed his dinner and his wine, and the company of cultivated men, and usually retired in good spirits. It was in the early morning that he felt the ache in his breast; it had something to do with waking in the early morning. It seemed to him that the grey dawn lasted so long here, the country was a long while in coming to life. The gardens and the fields were damp, heavy mists hung in the valley and obscured the mountains; hours went by before the sun could disperse those vapours and warm and purify the villages.

In New Mexico he always awoke a young man; not until he rose and began to shave did he realize that he was growing older. His first consciousness was a sense of the light dry wind blowing in through the windows, with the fragrance of hot sun and sage-brush and sweet clover; a wind that made one's body feel light and one's heart cry "To-day, to-day," like a child's.

Beautiful surroundings, the society of learned men, the charm of noble women, the graces of art, could not make up to him for the loss of those light-hearted mornings of the desert, for that wind that made one a boy again. He had noticed that this peculiar quality in the air of new countries vanished after they were tamed by man and made to bear harvests. Parts of Texas and Kansas that he had first known as open range had since been made into rich farming districts, and the air had quite lost that lightness, that dry aromatic odour. The moisture of plowed land, the heaviness of labour and growth and grain-bearing, utterly destroyed it; one could breathe that only on the bright edges of the world, on the great grass plains or the sage-brush desert.

That air would disappear from the whole earth in time, perhaps; but long after his day. He did not know just when it had become so necessary to him, but he had come back to die in exile for the sake of it. Something soft and wild and free, something that whispered to the ear on the pillow, lightened the heart, softly, softly picked the lock, slid the bolts, and released the prisoned spirit of man into the wind, into the blue and gold, into the morning, into the morning!

Book Nine: Chapter Six

During those last weeks of the Bishop's life he thought very little about death; it was the Past he was leaving. The future would take care of itself. But he had an intellectual curiosity about dying; about the changes that took place in a man's beliefs and scale of values. More and more life seemed to him an experience of the Ego, in no sense the Ego itself. This conviction, he believed, was something apart from his religious life; it was an enlightenment that came to him as a man, a human creature. And he noticed that he judged conduct differently now; his own and that of others. The mistakes of his life seemed unimportant; accidents that had occurred en route, like the shipwreck in Galveston harbour, or the runaway in which he was hurt when he was first on his way to New Mexico in search of his Bishopric. He observed also that there was no longer any perspective in his memories.

He remembered his winters with his cousins on the Mediterranean when he was a little boy, his student days in the Holy City, as clearly as he remembered the arrival of M. Molny and the building of his Cathedral. He was soon to have done with calendared time, and it had already ceased to count for him. He sat in the middle of his own consciousness; none of his former states of mind were lost or outgrown. They were all within reach of his hand, and all comprehensible. Sometimes, when Magdalena or Bernard came in and asked him a question, it took him several seconds to bring himself back to the present. He could see they thought his mind was failing; but it was only extraordinarily active in some other part of the great picture of his life--some part of which they knew nothing. When the occasion warranted he could return to the present. But there was not much present left; Father Joseph dead, the Olivares both dead, Kit Carson dead, only the minor characters of his life remained in present time. One morning, several weeks after the Bishop came back to Santa Fe, one of the strong people of the old deep days of life did appear, not in memory but in the flesh, in the shallow light of the present; Eusabio the Navajo.

Out on the Colorado Chiquito he had heard the word, passed on from one trading post to another, that the old Archbishop was failing, and the Indian came to Santa Fe.

He, too, was an old man now. Once again their fine hands clasped.

The Bishop brushed a drop of moisture from his eye. "I have wished for this meeting, my friend. I had thought of asking you to come, but it is a long way."

The old Navajo smiled. "Not long now, any more. I come on the cars, Padre. I get on the cars at Gallup, and the same day I am here. You remember when we come together once to Santa Fe from my country? How long it take us? Two weeks, pretty near. Men travel faster now, but I do not know if they go to better things."

"We must not try to know the future, Eusabio. It is better not. And Manuelito?"

"Manuelito is well; he still leads his people." Eusabio did not stay long, but he said he would come again to- morrow, as he had business in Santa Fe that would keep him for some days. He had no business there; but when he looked at Father Latour he said to himself, "It will not be long." After he was gone, the Bishop turned to Bernard; "My son, I have lived to see two great wrongs righted; I have seen the end of black slavery, and I have seen the Navajos restored to their own country." For many years Father Latour used to wonder if there would ever be an end to the Indian wars while there was one Navajo or Apache left alive. Too many traders and manufacturers made a rich profit out of that warfare; a political machine and immense capital were employed to keep it going.

Book Nine: Chapter Seven

Pueblo Bomito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico.

The Bishop's middle years in New Mexico had been clouded by the persecution of the Navajos and their expulsion from their own country. Through his friendship with Eusabio he had become interested in the Navajos soon after he first came to his new diocese, and he admired them; they stirred his imagination.

Though this nomad people were much slower to adopt white man's ways than the home-staying Indians who dwelt in pueblos, and were much more indifferent to missionaries and the white man's religion, Father Latour felt a superior strength in them. There was purpose and conviction behind their inscrutable reserve; something active and quick, something with an edge.

The expulsion of the Navajos from their country, which had been theirs no man knew how long, had seemed to him an injustice that cried to Heaven. Never could he forget that terrible winter when they were being hunted down and driven by thousands from their own reservation to the Bosque Redondo, three hundred miles away on the Pecos River. Hundreds of them, men, women, and children, perished from hunger and cold on the way; their sheep and horses died from exhaustion crossing the mountains. None ever went willingly; they were driven by starvation and the bayonet; captured in isolated bands, and brutally deported. It was his own misguided friend, Kit Carson, who finally subdued the last unconquered remnant of that people; who followed them into the depths of the Canyon de Chelly, whither they had fled from their grazing plains and pine forests to make their last stand. They were shepherds, with no property but their live-stock, encumbered by their women and children, poorly armed and with scanty ammunition. But this canyon had always before proved impenetrable to white troops. The Navajos believed it could not be taken. They believed that their old gods dwelt in the fastnesses of that canyon; like their Shiprock, it was an inviolate place, the very heart and centre of their life. Carson followed them down into the hidden world between those towering walls of red sandstone, spoiled their stores, destroyed their deep-sheltered corn-fields, cut down the terraced peach orchards so dear to them. When they saw all that was sacred to them laid waste, the Navajos lost heart.

They did not surrender; they simply ceased to fight, and were taken. Carson was a soldier under orders, and he did a soldier's brutal work. But the bravest of the Navajo chiefs he did not capture. Even after the crushing defeat of his people in the Canyon de Chelly, Manuelito was still at large. It was then that Eusabio came to Santa Fe to ask Bishop Latour to meet Manuelito at Zuni. As a priest, the Bishop knew that it was indiscreet to consent to a meeting with this outlawed chief; but he was a man, too, and a lover of justice. The request came to him in such a way that he could not refuse it.

River in Canyon de Chelly.

He went with Eusabio. Though the Government was offering a heavy reward for his person, living or dead, Manuelito rode off his own reservation down into Zuni in broad daylight, attended by some dozen followers, all on wretched, half-starved horses. He had been in hiding out in Eusabio's country on the Colorado Chiquito. It was Manuelito's hope that the Bishop would go to Washington and plead his people's cause before they were utterly destroyed. They asked nothing of the Government, he told Father Latour, but their religion, and their own land where they had lived from immemorial times. Their country, he explained, was a part of their religion; the two were inseparable. The Canyon de Chelly the Padre knew; in that canyon his people had lived when they were a small weak tribe; it had nourished and protected them; it was their mother. Moreover, their gods dwelt there--in those inaccessible white houses set in caverns up in the face of the cliffs, which were older than the white man's world, and which no living man had ever entered. Their gods were there, just as the Padre's God was in his church.

And north of the Canyon de Chelly was the Shiprock, a slender crag rising to a dizzy height, all alone out on a flat desert. Seen at a distance of fifty miles or so, that crag presents the figure of a one-masted fishing-boat under full sail, and the white man named it accordingly. But the Indian has another name; he believes that rock was once a ship of the air. Ages ago, Manuelito told the Bishop, that crag had moved through the air, bearing upon its summit the parents of the Navajo race from the place in the far north where all peoples were made,--and wherever it sank to earth was to be their land. It sank in a desert country, where it was hard for men to live. But they had found the Canyon de Chelly, where there was shelter and unfailing water. That canyon and the Shiprock were like kind parents to his people, places more sacred to them than churches, more sacred than any place is to the white man. How, then, could they go three hundred miles away and live in a strange land? Moreover, the Bosque Redondo was down on the Pecos, far east of the Rio Grande.

Manuelito drew a map in the sand, and explained to the Bishop how, from the very beginning, it had been enjoined that his people must never cross the Rio Grande on the east, or the Rio San Juan on the north, or the Rio Colorado on the west; if they did, the tribe would perish. If a great priest, like Father Latour, were to go to Washington and explain these things, perhaps the Government would listen. Father Latour tried to tell the Indian that in a Protestant country the one thing a Roman priest could not do was to interfere in matters of Government. Manuelito listened respectfully, but the Bishop saw that he did not believe him. When he had finished, the Navajo rose and said: "You are the friend of Cristobal, who hunts my people and drives them over the mountains to the Bosque Redondo. Tell your friend that he will never take me alive. He can come and kill me when he pleases. Two years ago I could not count my flocks; now I have thirty sheep and a few starving horses. My children are eating roots, and I do not care for my life. But my mother and my gods are in the West, and I will never cross the Rio Grande." He never did cross it. He lived in hiding until the return of his exiled people. For an unforeseen thing happened: The Bosque Redondo proved an utterly unsuitable country for the Navajos. It could have been farmed by irrigation, but they were nomad shepherds, not farmers. There was no pasture for their flocks. There was no firewood; they dug mesquite roots and dried them for fuel. It was an alkaline country, and hundreds of Indians died from bad water.

At last the Government at Washington admitted its mistake--which governments seldom do. After five years of exile, the remnant of the Navajo people were permitted to go back to their sacred places.

In 1875 the Bishop took his French architect on a pack trip into Arizona to show him something of the country before he returned to France, and he had the pleasure of seeing the Navajo horsemen riding free over their great plains again. The two Frenchmen went as far as the Canyon de Chelly to behold the strange cliff ruins; once more crops were growing down at the bottom of the world between the towering sandstone walls; sheep were grazing under the magnificent cottonwoods and drinking at the streams of sweet water; it was like an Indian Garden of Eden.

Rio Grande near Trucas on the High Road to Taos, New Mexico.

Now, when he was an old man and ill, scenes from those bygone times, dark and bright, flashed back to the Bishop: the terrible faces of the Navajos waiting at the place on the Rio Grande where they were being ferried across into exile; the long streams of survivors going back to their own country, driving their scanty flocks, carrying their old men and their children. Memories, too, of that time he had spent with Eusabio on the Little Colorado, in the early spring, when the lambing season was not yet over, –dark horsemen riding across the sands with orphan lambs in their arms– a young Navajo woman, giving a lamb her breast until a ewe was found for it. "Bernard," the old Bishop would murmur, "God has been very good to let me live to see a happy issue to those old wrongs. I do not believe, as I once did, that the Indian will perish. I believe that God will preserve him."

Window Rock, Arizona is the capital of the Navajo Nation.

On line source: DEATH COMES FOR THE ARCHBISHOP.

Thematic allusions: the antiquity of the land and its peoples

Themes | Who | What | When | Where

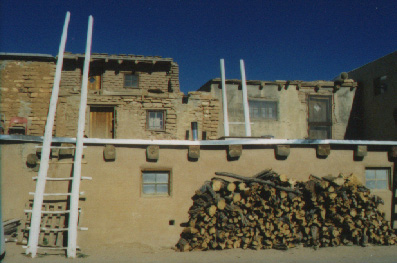

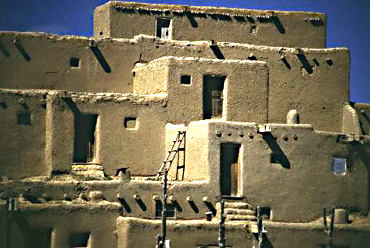

“When he approached the pueblo of Isleta, gleaming white across a low plain of gray sand, Father Latour's spirits rose. It was beautiful, that warm, rich whiteness of the church and the clustered town. The church and the Isleta houses were made of adobe, whitewashed with a bright gypsum.”

"Cather wrote of the young bishop that “There was no way in which he could transfer his own memories of European civilization into the Indian mind,”

“and he was quite willing to believe that behind Jacinto there was a long tradition, a story of experience, which no language could translate to him.”

“Every stone in that structure,” bishop Latour explained to himself, “every handful of earth in those many thousand pounds of adobe, was carried up the trail on the backs of men and boys and women. And the great carved beams of the roof — Father Latour looked at them with amazement. In all the plain through which he had come he had seen no trees but a few stunted piñons. He asked Jacinto where these huge timbers could have been found.

“Every stone in that structure,” bishop Latour explained to himself, “every handful of earth in those many thousand pounds of adobe, was carried up the trail on the backs of men and boys and women. And the great carved beams of the roof — Father Latour looked at them with amazement. In all the plain through which he had come he had seen no trees but a few stunted piñons. He asked Jacinto where these huge timbers could have been found.

“ ‘San Mateo mountain, I guess.'

“ ‘But the San Mateo mountains must be 40 or 50 miles away. How could they bring such timbers?'

“Jacinto shrugged. ‘Ácomas carry.' Certainly there was no other explanation.”

Acoma, is called the "City of the Sky" and its people then were the Acomas, an older pueblo people of the Pre-Spanish southwest.

The above story- line is thanks to N.Y. Times:

"Entering the World of Willa Cather’s Archbishop"

By MARY DUENWALD, New York Times, August 26, 2007.