The

cultural, economic, and ecological significance of the American Everglades

by Joseph Siry

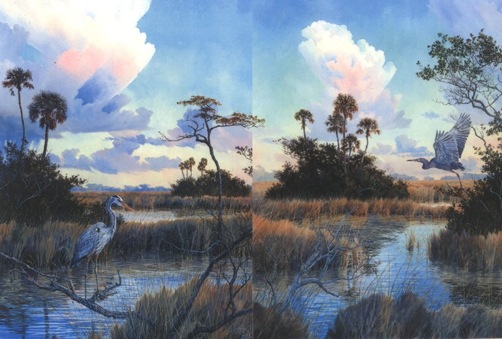

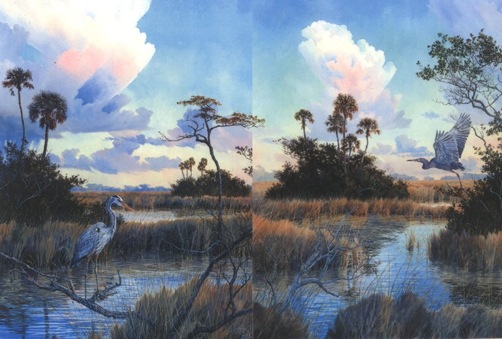

An absence of

angularity in the nearly flat horizon of the Everglades accentuates the bird life  and draws attention to the vegetation rising up

out of the mud and algae of this hundred mile wide utterly flat, subtropical

river. Wild beyond imagining these everglades are necessary for civilization

in South Florida. Miami, Fort Lauderdale and Key West have to drink fresh

water and that water was once stored in, within the vegetation and below the

bed of these now vastly diminished glades. The widest river on earth is damaged

and in need of repairs. These extensive and unprecedented repairs may require a multibillion dollar bypass surgery and the closure of industrial agriculture in the form of sugar plantations before the patient can be released from intensive care. While the birds are clues to understanding the incredibly productive fishery here, they also indicate this patient's prognosis. For the future of development in the state depends on the full recovery of these tropical prairies, hardwood forests, mangrove swamps, coral reefs, and near endlessly wild islands.

and draws attention to the vegetation rising up

out of the mud and algae of this hundred mile wide utterly flat, subtropical

river. Wild beyond imagining these everglades are necessary for civilization

in South Florida. Miami, Fort Lauderdale and Key West have to drink fresh

water and that water was once stored in, within the vegetation and below the

bed of these now vastly diminished glades. The widest river on earth is damaged

and in need of repairs. These extensive and unprecedented repairs may require a multibillion dollar bypass surgery and the closure of industrial agriculture in the form of sugar plantations before the patient can be released from intensive care. While the birds are clues to understanding the incredibly productive fishery here, they also indicate this patient's prognosis. For the future of development in the state depends on the full recovery of these tropical prairies, hardwood forests, mangrove swamps, coral reefs, and near endlessly wild islands.

1 | 2 | 3| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

Without the Everglades,

freshwater evaporates and without sufficient drinkable water, life in south Florida shrinks,

population migrates away and only the hardy few would ever remain. The economic future

of over half of the state's population rests on finding sufficient water storage for human

consumption and wildlife. The everglades is a barometer of how effective that

search for storage facilities will be given rising population pressure, the necessity of agriculture,

and the demand for more living space. These glades are also a measure of our

commitment to a new aspect of ecological conservation that must become the foundation

of water resource allocation issues.

Established as a National Park over fifty years ago, the

Everglades remains on the critical list, a patient in need of radical bypass surgery because

of pollution and water withdrawals upstream, invasive exotic species, mining of the lime rock

for construction concrete, road building, mercury contamination of fisheries and extensive

agricultural reclamation. Over the past thirty years, as sea level has risen,

the salt-tolerant

red mangrove forest has extended inland by hundreds of acres to replace the once broad sawgrass

plains. Similarly in highly enriched freshwater marshes cattails have crowded out the native saw grass prairies because typha grasses roots tolerate high nutrient conditions with ample phosphorus and nitrogen in the water.

The rock lime of

Florida would be bare and parched without the water as this stretch of land lies beside the

salt sea in these otherwise desert latitudes of the earth. The shelf whereupon the glades sawgrass,

stunted cypress, and salt loving mangrove trees grow is the fossil debris of marine organisms

long dead whose compacted skeletons form the marl, or white clay supports the fish,

birds, mammals and plants of this sub-tropical grassland. The limestone that forms the

bedrock of this area was formed nearly nine million years ago in a shallow warm sea. Here

the land itself is biogenic or, formed by living things.

The glades' foundation

is made of once living sea creatures in whose shells, bones and living tissue the

calcium of sea water was strained, concentrated and deposited into fossils.

As Douglas reminds

us this rock foundation collected debris from the surrounding seas and when the sea level

dropped -- due to glaciation -- the glades emerges out of geological time from the sea and

the sun 10,000 years ago. Douglas writes that "In that decay" of vegetation "a wide band of

jungle trees sprang up." [P4 page 171]

Water and life

are wedded among flat tables where the sea and the river of grass intermingle and deeply exchange

nutrients that nourish the wealth of vegetation and animal life. This association of

saw grass, cypress and mangrove forests is what had once changed the limestone rock

base of south Florida into the hydroponics of this wild profusion of new, old, and decaying life.

For over fifty years, Marjory Stoneman Douglas' book entitled, The Everglades: River

of Grass, (1947) revealed the ongoing necessity of these extensive and diverse wetlands

in Florida's history and life. In the section of the book called "Life on the Rock," She suggests

that "The saw grass and the water made the Everglades both simple and unique." These

wet prairies of grasses, lichens, birds, and reptiles are nothing compared to diverse

array of the insects.

In that chapter

"Life on the Rock," Douglas fills her

pages with as many of the sample of everglades species

as the page is capable of holding. By doing this she demonstrates to the avid reader the

number of different species that adapt well to these alternate wet and dry seasons of the

tropical savannas. Becalmed in a desert hot sun the moisture of these glades relentlessly evaporates

to drive the accumulating clouds to burst into the life giving rain.

Douglas teaches

us about both the function and the wonder of glades wildlife by simply suggesting that

"One begins with the plants." By that she directly reveals the important role that vegetation

plays in providing human civilization with basic necessities of life. But just

as water sustains

the plant life so it forms the vital ingredient because water drives "a diversity of life" that has

colonized and "lives upon the rock that holds it. The saw grass in its essential harshness

supports little else." Half a century ago, Douglas recognized that the diversity, or richness

of species should compel us to save the land for posterity as an example of the

biotic wealth of these sub-tropical climates. She realized the transcendent values associated

with these glades. But she also warned about the essential role the water flow played in

the economy of South Florida.

Because only a fragment of the Everglades and its estuary

Florida Bay were protected as a National Park the future of the regions' wildlife remained

a problem. Saving large tracts

of land to protect ecological associations of plants and animals, was thought to be a

necessary initial step in conservation of resources when the glades caught Congress' attention

in the late 1930s. It took nearly a decade to actually move from the paper authorization

to the creation of the National Park by Congress and President Truman in 1947. During

that time significant parcels of high quality landscape and ecologically significant shorelines

were removed from inclusion in the 1.2 million acre National Park.

These lands included

Key Largo, South Biscayne Bay and what is today called the Big Cypress preserve,

originally proposed to protect 2.2 million acres. In the race between the sentiment to save

ecologically rare vegetational communities and the drive to earn a return on investments

three-fourths of the 8.8 million acres of original everglades was lost to the lure of a new gold.

This hard currency was waterfront land for housing developments to feed the post war

demands and the necessity for agricultural development to feed the growing cities

of Miami, Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach. With agriculture came an ever increasing

thirst for water which peaked in 1990 at over 2.5 billion gallons per day!

When Florida's

population was still small, Douglas admonished us that "The saw grass and the water made

the Everglades both simple and unique." But like any neighborhood, the glades are

also the place where numerous creatures live out there entire lives. Others migrate through

these extensive grasslands. Once the patrimony of native peoples, the glades today is

the center of a fierce fight between conservation and development that tests the American commitment

to the environmental restoration of natural habitats.

As a natural place Douglas tells

us that there is no replacement for the original glades. Not even the Pantanal of South

America is the same as the everglades at the south and lower ends of the Kissimmee River

and Lake Okeechobee. [page 170] The glades are also the mother of a series of grassland

prairies that once spread all across Florida. There water and calcium rich limestone mingle

begetting rich associations that support the birds and mammals that Douglas so well

catalogued. She captured the spirit of this place just at the time it was being set aside in the

traditional manner of protecting the mouth of this river as a National Park. Because of the

very pine trees that colonized the dried sand banks and the cypress that grew up in the wet sinkholes

or along lakeshores, early Florida pioneers were assured of sturdy building materials

that could withstand the humid climate and the rotting vegetation all around them. Over

seventy years ago, only the edges of the glades were settled and the technology of road

building across a wet swamp had just begun. Built of the sand and the sea, as Zora Neale

Hurston, the anthropologist, reminds Floridians, the state is a geological sand bar adrift

in a tropical sea peopled by the strangest freight of life this side of the Pantanal in southern

Brazil.

Broadly speaking

the trees of the eastern and western sides of the narrowed peninsula differ with custard

apple bottoms to the southwest in contrast to willow & elder bottoms to the southeast.

These stands have been severely eroded due to the spread of invasive exotic trees, principally

the Australian Maleleuca and the South American, Brazilian Pepper. These ornamental

trees have contributed to a simplification of the everglade's vegetation.

Today the "the

enormous darkness without light of the saw-grass river." described by Douglas, is threatened

from introduced exotic plants that have escaped cultivation, and crowded out native

trees. [P8] Here, the four thousand year old association of plant communities that

defied human trespass until the late 1920s. [P3] Instead of pine

on the highest rock ridges of the Caribbean Pine or Dade County pine, the suburbs have introduced

a pan equatorial tropical flora from all over the world to adorn the native flora of

south Florida. Some critics warn the transplanting is forming the basis of a future "homogecene

period" where a few dominant species of plants cause a consequent decline in animals.

As the saw palmettos

retreated in the face of Philippine and Pacific palms the decline in animals and especially

bird life became apparent. Residential growth adversely affected the deer populations

and particularly a variety in the Florida keys. Once included in an early version of the

Everglades National Park, Florida Bay shore along the Florida Keys was originally meant

to be protected. Construction of the overseas highway and the aqueduct to the naval base

assured that the density of population in the Florida Keys was poised to go from absence of

people to excessively destructive densities of people in fifty years. Like the glades the keys

emerge as a case study of the consequences of population growth. [P13 page 172] Key deer are

a subspecies of the mainland white tailed deer described by Douglas as "The small brown

Florida deer step neatly at the edge of pine forests like these." [P14]

From animals to

the smallest wildflowers, Douglas captures the shock of this limerock's living prairies

and forested hammocks as she describes the "tiny wild poinsettias with their small brush strokes

of scarlet." P14 These details of the vegetation so characteristic of Florida is to present

the everglades as a microcosm, such as a Wisconsin lake or Silver Springs. She conveys

the centrality of this river and to all rivers when she says that "in the middle of the saw-grass

river,even the pines grow tall to show where the rock lies." And this marriage of limestone

or soluble calcium and water is the heat engine that drives this fountain of clear,

shallow, nutrient rich water that feeds "The whole world of the pines and of the rocks hums

and glistens and stings with life." [P21]

Like many stranded

ecological systems the mix of predators influences the number and abundance of deer,

rabbits, raccoons and mice. Douglas remarks that the glades rattlesnake -- "has made him

the king among all these beasts."[P15] Vying with the alligator, salt water crocodile,

and the Florida panther, the snakes of the Everglades form a dynamic food web that ultimately

rests on the bacteria, algae and plants that sustain the invertebrate populations upon

which the economically vital commercial fisheries and the ecologically vital bird populations

feed. As almost a warning not to tamper with the glades Douglas writes that "Life

is everywhere here too, infinite and divisible." [P26 page 174]

Long gone in the

three booms following World War 1 are "The live oaks," once comprising "that great Miami

hammock, the largest tropical jungle on the North American mainland, which spread south

of the Miami River like a dark cloud along that crumbling, spring-fed ledge of rock." [P27

pages 174-75] As if they were obstacles in the way of progress the oaks became furniture

and finished paneling in the myriad houses built after the numerous hurricanes of the

1920s and 1930s. Amidst these forests were a diverse array of ferns with "their roots deep

in the rotting limestone shelves among wet potholes green-shadowed with the richest fern

life in the world." [P27 page 175] Thus Douglas, in a few pages, fills the everglades with

the array of life akin to some relic of warmer, swamp dominated times when insects, reptiles

and mammals commingled prior to the appearance of humankind.

Every thing in

Florida adjusts to either fire or water in a contest for space that defies the notion that nature

is a kindly, balanced parent. "About the live oaks is waged the central drama of all this

jungle," she writes recalling that, "the silent, fighting creeping

struggle for sunlight of the

strangler fig." This tree the Ficus aurea is dropped as a seed by feeding birds

in the treetops of

oak or Sabal palm forests and grows to eventually surround the trunk -- thus squeezing the nutrients

and life out of the live oak, palms or tropical hardwoods it grows around-- in this

desperate struggle for sunlight, water and space to grow. [P28] In this struggle of the

strangler fig and the live oak is a homily about conditions for life and human society throughout

this remodeled landscape. In adjusting to immersion in this baptismal water that jets

out of springs in the porous limerock, Florida's vegetation changes according the appearance

and evaporation of water. "The water oaks grow taller and more regular than the live oaks....

Both crowd down to the glossy water and make landscapes like old dim pictures where

the deer came down delicately and the cows stand, to drink among their own reflections."

[P34, page 176] Douglas knew that water shortages would occur as the Atlantic ridge

of Florida was bulldozed to accommodate six million people in sixty years.

Douglas today recalls

for us that "In the great Miami hammock, along the banks of almost every river, bordering

the salt marshes, scattered in the thinner pinelands, making their own shapely and recognizable

island-hammocks within the Everglades river, everywhere, actually, except

in the densest growth of the saw-grass itself, stands the Sabal palmetto."

The state tree

Douglas concedes "...is called the cabbage palm." She writes that "They make dense islands

in the sawgrass river." [P35], Out of our collective memory Douglas describes the mouth

of one of the springs that once flowed when the everglades was a coherent and functionally

regular waterway. This landscape is like a scene out of Africa, hot expanses of grasslands

uninterrupted except by hammocks of palmetto. Now this landscape is only preserved

in relic areas protected by state, county or national parks. The rapid growth

of the area forced

upon the now subdivided and leveed everglades a new role.

This role was to

function as a necessary agricultural producer of tomatoes or sugar grown on the rich organic

muck soil of the everglades that had accumulated from fast growth and decay cycles. And

with such agriculture came the necessity of a water storage area. Once derided as storm

drains or retention ponds the swamps and wet prairies would soon be needed for water

storage throughout the fresh water reaches of the state. Such places are marked as Douglas

reminds us, by "the enduring cypress." [P37 page 176]

The cypress trees

of Florida characterize a last refuge today for the endangered panther in the Big Cypress

Swamp preserve added to the glades in the 1970s to assist in restoring the fresh water flow

to ailing Florida Bay. Douglas combines the ambivalent values of this tree that led to its

widespread demise in all but the wettest and protected areas of Florida. She explains that "It

is a fine timber tree..., it is most strangely beautiful." [P37 page 177]

Like all beautiful,

natural things that people desire, the cypress was logged heavily, before the protection

was afforded remnant stands. Strangely haunting vegetation was described by Douglas as coniferous

forests supported by "the root like extension into the air, like dead stumps, called

cypress knees, which are thought to aerate the mud bound roots."

In her description

of the Big Cypress Swamp, Douglas wrote that "The brown deer, the pale-colored lithe

beautiful panthers that feed on them, the tuft-eared wildcats with their high-angled hind

legs, the opossum and the rats and the rabbits have lived in and around it and the Devil's

Garden and the higher pinelands to the west since this world began." [P42]

Visual distortion

furthers a mood of strange nocturnal sounds in Douglas writings where "The great barred

owls hoot far off in the nights..." [P42]

She describes hunts

that inevitably end in panther deaths because these cats "never to be tamed, are shot."

[P43] Here on this predatory frontier is another story by which she conveys the strangeness

of the glades even before they were dismembered from drainage, canals, pumps and

levees. In making land out of water humans made a relentless dilemma where once there had

been adaptive response.

As a biotic community

"the Glades' first citizen, the otter, his broad jolly muzzle explores everything,

tests everything, knows everything." she writes that "...this is his home."[ P44, P45

page 178]

Douglas writes evocatively of "Lake jungles, pine, live oak, cabbage palmetto,

cypress, each has its region and its associated life. As the islands in the saw grass pointed

southward in the water currents, their vegetation changes like their banks, from the

temperate to the subtropic, to the full crammed tropic of the south." The everglades in the

hands of Douglas emerged as the litmus test of Florida sense of itself and of its mission

as a group of settlers intent of preserving the existing remnants of this oft ballyhooed paradise. [P48

page 178]

The protection

of this watery realm of the Everglades was not effectively secured by the creation of the

National Park because of the commercial interference with the flow of water into the park.

From the 1920s with the construction of levees around Lake Okeechobee, to the building of

US highway 40 across the glades from Naples to Miami in 1930s, the race between developmental

erosion of ecological values and the lure of real estate left the Everglades Park

lands behind in the proverbial dust.

Until the late 1950s few save Douglas and her ecologically

enlightened circle of naturalists and birders considered the serious consequences of

this loss of shorelines, wetlands, and canals that robbed this National Park of its life sustaining

water. Because the park protected 830 species their lives hung by a thread of

life sustaining water. In 1843, a St. Augustine lawyer had convinced Congress of the

feasibility of draining the everglades, long afterward, right after World War Two the

dream became a reality due to extensive flooding during a wet year in 1947.

The world heritage

importance of the Everglades make this national treasure more than the sum of its ecologically

functioning parts. Twelve distinct habitats comprise the vegetational associations in

the region sprawling across the boundaries of the park, of the land, of even the water itself.

For example, the park embodies 800 square miles of Florida Bay as protected areas

of mangrove or shell islands the home of wading birds, sea birds and an occasional pelagic

or intercontinental migrating birds or turtles. Despite the region's rarity, isolation, and

wildlife it is being deamaged due to upland interference with run-off.

The Everglades

National Park is considered by ecologist Mark Harwell as the most endangered in the

country. Polluted water, fragmented habitats and unseasonal water pumping and then

dumping of contaminated water has killed the everglades as a fountain and Florida Bay as

the nursery of fish and bird life in south Florida.

Aware of the critical

situation a coalition of environmental groups encouraged the National Park Service to

file court action against the State water entity (South Florida Water Management District)

legally responsible for the allocation, flow and disposal of polluted water in the region

feeding the Everglades National Park.

To increase the pressure on a state legislature that

lacked the conviction and vision to restore the everglades, Florida environmental organizations

promoted an amendment to the State constitution with far reaching implications

since it embodies in law the notion that those who pollute should pay to clean up their

pollution. Although never enforced by a recalcitrant and uneducated legislature, that Constitutional

amendment marks the rift in the state that threatens to engulf the everglades and

destroy the river of grass.

As

the focus of ecological conservation the Everglades today is the litmus test  case of our commitment to

restoring the environment in order to revive the natural and commercial economy. For without

sufficient water, sugar, tomatoes, golf courses and swimming pools alike will dry

up in the race to covet the remaining fresh water that inheres in the limestone rock because of

the action of vegetation under the blazing sun nourishing wildlife and fisheries. Wildlife

must be protected in water allocation or else we win the race for water only to lose the wading

birds who are the biotic souls of these wetlands.

case of our commitment to

restoring the environment in order to revive the natural and commercial economy. For without

sufficient water, sugar, tomatoes, golf courses and swimming pools alike will dry

up in the race to covet the remaining fresh water that inheres in the limestone rock because of

the action of vegetation under the blazing sun nourishing wildlife and fisheries. Wildlife

must be protected in water allocation or else we win the race for water only to lose the wading

birds who are the biotic souls of these wetlands.

1 | 2 | 3| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

return to start

Notes:

the Indians found

their first source of life.... ferny green cycads, plants older than this rock,

with yellow and orange

cones for flowers

and great thick roots. This is the Ôcoontie' of the oldest Indian legend."

[P18 page 173]

Coontie grounds

north of the Miami River, the succession from pine to Live Oak [P22 page 174]

migrations -- "it

is impossible to name all the warblers that pass through here." [ P23]

"dry Resurrection

ferns" in the limbs of Live Oaks. [ P25]

"the black and

white caracara, that the Mexicans take for their national eagle, cries harshly"

[ P26]

"and ferns innumerable."

leather ferns, "maidenhair and Boston ferns and brackens"

Harwell, Mark,

"Ecosystem Management of South Florida," BioScience, 47:8, September, 1997.

pp.

499-512. p. 502.

The list is long

but among the outstanding groups are "Friends of the Everglades," "Save the

Everglades,"

Florida and National

Audubon Societies, Sierra Club, World Wildlife Fund, and Isaac Walton League.

and draws attention to the vegetation rising up

out of the mud and algae of this hundred mile wide utterly flat, subtropical

river. Wild beyond imagining these everglades are necessary for civilization

in South Florida. Miami, Fort Lauderdale and Key West have to drink fresh

water and that water was once stored in, within the vegetation and below the

bed of these now vastly diminished glades. The widest river on earth is damaged

and in need of repairs. These extensive and unprecedented repairs may require a multibillion dollar bypass surgery and the closure of industrial agriculture in the form of sugar plantations before the patient can be released from intensive care. While the birds are clues to understanding the incredibly productive fishery here, they also indicate this patient's prognosis. For the future of development in the state depends on the full recovery of these tropical prairies, hardwood forests, mangrove swamps, coral reefs, and near endlessly wild islands.

and draws attention to the vegetation rising up

out of the mud and algae of this hundred mile wide utterly flat, subtropical

river. Wild beyond imagining these everglades are necessary for civilization

in South Florida. Miami, Fort Lauderdale and Key West have to drink fresh

water and that water was once stored in, within the vegetation and below the

bed of these now vastly diminished glades. The widest river on earth is damaged

and in need of repairs. These extensive and unprecedented repairs may require a multibillion dollar bypass surgery and the closure of industrial agriculture in the form of sugar plantations before the patient can be released from intensive care. While the birds are clues to understanding the incredibly productive fishery here, they also indicate this patient's prognosis. For the future of development in the state depends on the full recovery of these tropical prairies, hardwood forests, mangrove swamps, coral reefs, and near endlessly wild islands.

case of our commitment to

restoring the environment in order to revive the natural and commercial economy. For without

sufficient water, sugar, tomatoes, golf courses and swimming pools alike will dry

up in the race to covet the remaining fresh water that inheres in the limestone rock because of

the action of vegetation under the blazing sun nourishing wildlife and fisheries. Wildlife

must be protected in water allocation or else we win the race for water only to lose the wading

birds who are the biotic souls of these wetlands.

case of our commitment to

restoring the environment in order to revive the natural and commercial economy. For without

sufficient water, sugar, tomatoes, golf courses and swimming pools alike will dry

up in the race to covet the remaining fresh water that inheres in the limestone rock because of

the action of vegetation under the blazing sun nourishing wildlife and fisheries. Wildlife

must be protected in water allocation or else we win the race for water only to lose the wading

birds who are the biotic souls of these wetlands.