Mangroves of the Tropic Seashores

by Joseph Siry, Rollins

College

Trees that grow in the sea, along

the shore and up into the mouths of rivers are generically referred to as

mangroves. The name is descriptive. Trees growing in this association are not

related to one another, nor do they adapt similarly to the alternating changes

in water quality. The water quality changes from fresh to salt and some

variation in between.

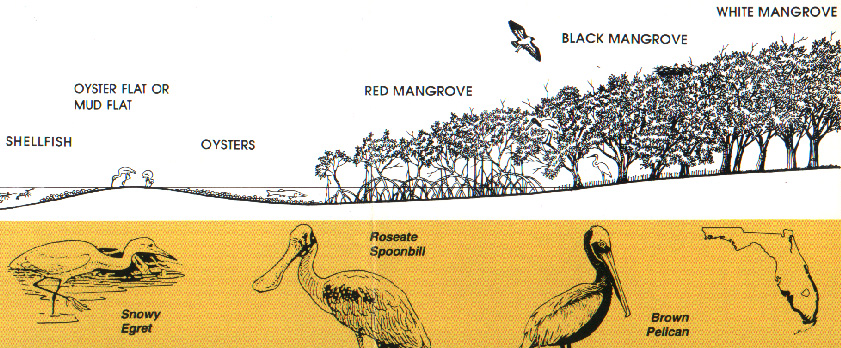

The dominant members of this watery domain are red,

white, and black mangroves moving from the deepest water to the shallower edge

of the shoreline (See p. 3). The three

varieties of important mangroves worldwide and in Guyana, Mexico and the

Caribbean, are also represented Florida:

Common

name Latin

species name.

Red, is called: Rhizophora mangle L.

White, is called: Languncularia racemosa (L.) Gaertn. f.

Black

is called: Avicennia germinans (L.) L.

These are unusual plants adapted to stressful conditions

that manage surviving to provide shelter for an incredible array of other wet

and dry living creatures.

Besides the capacity to hold the shoreline from

eroding --even under the surge tides of tremendous tropical storms-- mangroves

literally feed the numerous creatures of the coastal tropical lagoons,

estuaries and rivers where these trees thrive. Tropical coastal forests free from frost develop large stands of

trees 25 to 45 feet (12 meters) sheltering pelicans, spoonbills, parrots and

macaws. On the roots of these trees are attached the oysters, snails, and

mussels that feed by filtering the waters of these warm tropical seas. The root

systems allow mangroves to reestablish healthy trees despite brutal hurricanes.

Mangroves and water are wedded in a productive

community serving as a cornucopia and haven for marine and land creatures. Mud

and sediment collect at the base of the mangroves where clams and worms feed on

the falling leaves. Decaying leaves from these trees are the perfect food or

microscopic floaters in the water that feed most of the fish. Fish and birds

densely populate these forests for this very reason; a lot of food.

By providing food, shelter and a livelihood for

creatures exploiting the ocean shore, mangroves growing in the quiet shallow

bays and lagoons of tropics are a lesson in global ecology. They represent

species that girdle the equatorial latitudes from China to Australia or

Louisiana to Brazil and from Florida to India. In the islands of Indonesia

alone mangroves in isolation diversified to a greater extent than anywhere

else. Africa, the Americas and Asia are characterized by different species of

mangroves, but coastal fisheries of all these places depend on the productivity

of the Mangrove belt.

Mangroves colonize and trap the sediments in the river mouths of the Amazon, Orinoco, the Congo, the Mekong and Ganges rivers. They are the forested front-line defense against the rising seas. On Guyana’s northern coast the cost of replacing mangrove-lined shores with coastal engineering works is tangibly manifest in sea walls and dikes with tidal sluice gates. A significant portion of the gross domestic product involves maintaining this revetment against the sea to protect rice and sugar fields. Termed coastal defenses, nearly 70% of Guyana’s marine shore is lined with sea walls or levees. The remaining coastal areas and river mouths are lined with mangrove forests. Wherever found, these salt-water forests should be understood as an emporium and feed-store of the seas.

(524 words)

Contents of Lesson Plan (Outline)

1

Introduction “Mangroves of the Tropic Seashores”

i. Derivation of the term

ii. Zonation diagram

2 The

Life of a Red Mangrove Seed

origins,

usage and meaning

mangrove

species: 34 worldwide

4

necessary conditions

importance

and loss

ecological

significance

4 Abiotic

constraints

4 Abiotic

constraints

substrate

hydrology

minerals

& nutrients

temperature

5 Morphological

Adaptations

roots

salt

seed

dispersal

Avicennia germinans. Leaves, Keys, 1999.

6 Community

Structure and dynamics

“torrid

zones,” equatorial belts

Atlantic-Caribbean

Atlantic-Caribbean

Indo-Pacific

8 Zonation

(see bottom of page 3)

9 Forest

structure

primary

productivity

peat

accumulation

Rhizophora mangle. Isle in

Florida Bay, 1989.

marine

terrestrial

11 Human

values, uses, diagnosis and prognosis

subsistence

commercial

recreational

12

Sea

level changes and mangrove forests. Taken from Dr. Hal Wanless work.

1. Introduction, a. Derivation of the term:

Mangrove is a designation for trees

growing along the seashore derived from two words of Portuguese and English

origins corrupted together to designate members of these maritime forests. The

Portuguese word mangue, meaning tree

and the English word grove, for any collection

of trees are the two words: mang + grove combining

to form mangrove.

Western science’s awareness of:

Aristotle is said to have raised mangroves from seeds sent to him when

Alexander’s armies invaded the Indus Valley in 326 BC. A rich source of

fisheries in Asia and Africa the European voyages of discovery found these

forests in Africa and the America’s, as well.

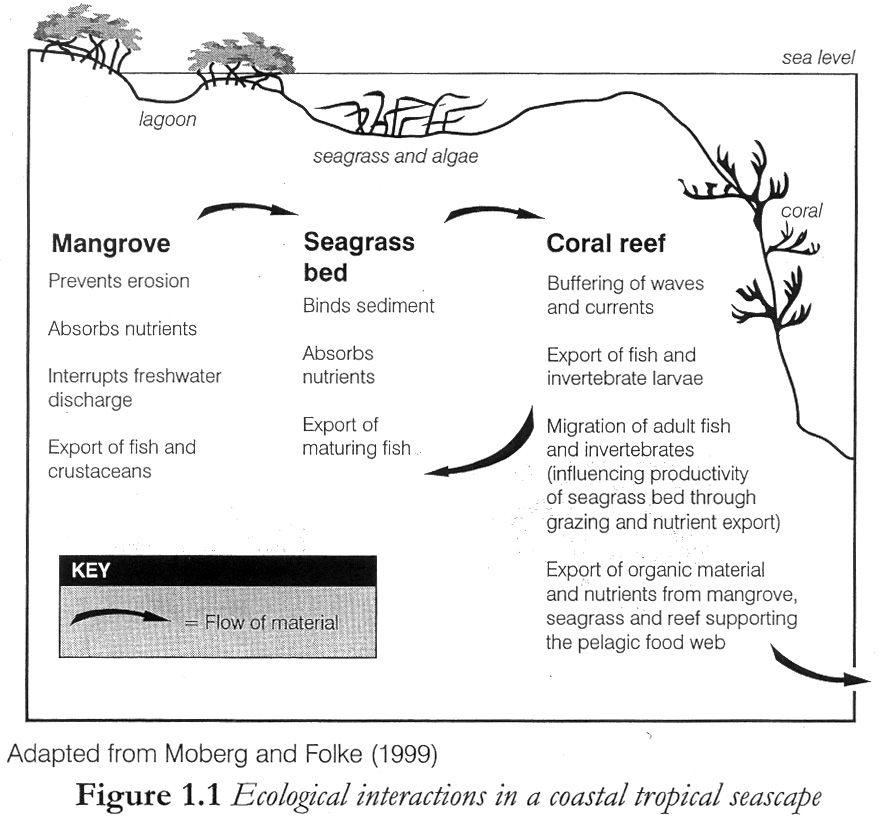

B. Zonation, The varieties (three or four) of mangroves that you see on the Florida coast from the southern keys north to Tampa Bay and the Indian River Lagoon, are not as robust as the Caribbean and South American forests, nor do they contain as many different species (richness or diversity) as do the Indo-Pacific regions of the tropical seashores. There are five to seven species of mangroves throughout Indo-Pacific seashores. Where the Guyana Shield meets the Atlantic Ocean south and east of the Lesser Antilles, the mangroves reach fifty to seventy-five feet in height compared to thirty feet or less along Florida’s more protected shores.

Nearshore and shoreline zonation schematic for a typical tropical marine habitat:

Bay

Littoral Land

ß------- edge

effect ------ą

Zones ß-------------- flood plain

Sublittoral Supra littoral

tidelands

2

The Life of a Red Mangrove Seed

Late in the summer after the bloom of small yellowish-white flowers is nearing its end, the fertilized seeds of the red mangrove begins to grow. Germinating on the branch where insects or wind previously deposited the pollen required to fertilize the red mangroves, the seed grows, lengthening from a pointy nub to a long gracefully curved, 10 to 11 inch long, seed that hangs pendulously from the end of the tree’s many branches. The shape is such that when shaken loose from the tree it either vertically floats as plankton or sinks into the mud. From here grows a tree that adjusts to one among the most stressful conditions of forest life on earth, the seas’ rim.

3 Definition of Mangroves,

a. origins, usage and meaning - by way of the Portuguese mango and Spanish mangle fron an original Taino word

b. mangrove species: 34 worldwide: These are an association of plants, trees, and fungus living together –the different species comprising such forests are not closely related trees. Thus, mangroves represent and example of convergent evolution where very distinct lineages of say Luguncularia racemosa and Rhizophora mangle. The white mangrove or Luguncularia racemosa is actually a member of the Combretaceae family, which is a distinctly different lineage of trees from either the red mangrove or more extensive black mangrove.

Florida tree specialist, Gil Nelson, writes “Even more confounding is the fact that the term [mangrove] is used to group plants together solely by similar ecological characteristics.” He goes on to emphasize that “Worldwide the term mangrove is most accurately applied to those tropical and subtropical trees and shrubs that are typically found along muddy and saltwater shorelines” where these trees “face environmental limitations to which few woody species have been able to adapt.”

(Gil Nelson, p. 99, The Trees of Florida.)

c.

Four

necessary conditions

i. salt water (may be brackish) from four to three tenths of a percent salt.

ii. low energy waves (small waves, calm water, or no wake), some surrent.

iii. soil: fine sand, marl, clay or organic mud soils (substrate)

iv. nutrients: calcium, nitrogen, carbon, phosphorus, sulphur, etc.

d.

Importance

and loss

i. Magnitude of their functions and ecological services:

1 of 4 sources of

photosynthesis along the shore

Protects

the shoreline from erosion and storm surge

Habitat

for invertebrates, fish, birds and mammals

Nesting

for Frigate birds, herons, egrets, and warblers.

Feeding

areas for roseate spoonbills, ibis, and flamingoes.

Used for mariculture to raise shrimp in developing nations.

ii. Once extensive wetlands, nationally and worldwide, mangroves have become locally diminished by as much as 50% to 90% of their original range.

i. nursery areas (habitat) for fish to grow to greater size in bays and oceans.

ii. physically protect the bays and estuaries where sea grasses thrive adjacent to mangrove shores in clear, shallow water.

iii. rich sources of b-vitamins, anaerobic bacteria, and growing

iv. places for lichens,

marine algae, bryozoans, mollusks and sponges that filter feed and remove

wasted from the surrounding waters.

a. substrate. Mud or fine sand bottoms for roots to penetrate and support the tree’s trunk which in: Black mangroves may grow as high as 25 meters (75 feet)

5 Morphological Adaptations

a. Roots, tolerate submersion in salt water and anoxic mud. Black possess pheumatophores projecting up and Red have readily discernable “prop” roots arching down into the water.

b. Salt, red species block salt water whereas white and black excrete salts.

c. Seed, viviparous,

maturing on the stalk. The dispersal is enhanced by tidal flow once or twice

per day back and forth along the appropriate submerged lands for seedlings to

colonize.

6 Community Structure and dynamics

a. Coastal zones are extensive

and account for approximately 8% of

the Earth’s surface where ocean waters cover two thirds or more area. The

mangrove shorelines, while probably accounting to no more than 2% of that

coastal surface are sources of net primary productivity. The significance of

this ability to convert sunligth, water and nutrients into food makes these

areas valuable as carbon sinks of greater importance than their surface area

alone may indicate.

b. Because of the woody (containing starch and lignin) character of mangrove forests,

the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed from the air by juvenile and young trees

during the light phase of photosynthesis make mangroves more effective in

sequestering or retaining carbon in the soil and in their structure than the

equally important marsh grass meadows of the more temperate shore. Like

marshes, mangroves may stabilize shores and adjacent barrier islands.

7

Geographical Distribution

b. Atlantic-Caribbean Sea: south to the Amazon and Brazil, North to Gulf of Mexico.

c. Indo-Pacific: south to Queensland,

Australia; north to the Philippines, Thailand & Vietnam.

8 Zonation

The partitioning of the land or sea with respect to recognizable features or factors that distinguish one elevation or extent of an area from an adjacent or distant, contrasting area.

9 Forest structure

a. primary productivity – leaves and canopy exposed to light, marine algae, bromeliads (air plants), lichens and orchids, blue-green bacteria (cyanobacteria) are all photosynthetic.

b. peat accumulation

– dead and decaying (detritus) matter can be compacted in the absence of oxygen to form undecayed

organic soils laden with nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur & carbon.

c. carbon sequestration and carbon banking

10 Associated Animals

a. Marine: shrimp, stone crabs, mullet, redfish, snapper, lobster, manatees.

b. Terrestrial: deer, raccoon, spoonbills, ibis, turtles, egrets, herons, frogs.

11 Human values, uses, diagnosis and

prognosis

a. subsistence – fishing, hunting and gathering, medicinal extracts.

b. commercial – fisheries, mariculture, lumber, fuel timber for charcoal or fire, dumps.

c. recreational – snorkeling, sport fishing, diving,

wilderness packing, bird watching.

d. Flood protection from tsunami, storm surges, and accumulating rainfall.

12 Sea level changes and mangrove forests.

Excertpts from a report : COASTAL ECOSYSTEMS • Chapter 2 Harold Wanless, Ph.D.

University of Miami

Coastal Marshes and Swamps.

North

of Tampa and Vero Beach Spartina salt marshes dominate saline wetlands,

primarily on the margins of lagoon and estuaries. To the south, coastal mangrove forests

dominate the coastal wetlands in south Florida. Both communities have the potential to

build upwards rapidly over the short term, but neither has the ability to

maintain pace with rapid sea level rise in the presence of catastrophic

setbacks.

Hurricanes

and fire are the principal setbacks in the Spartina community. Hurricanes,

freezes and impoundments are the principal setbacks in the mangrove

community.

These

swamp and marsh communities are dependent on nearshore buildups of sand and mud

to expand seaward or to recolonize wetland margins lost during hurricanes. As a result, high rates of sea level

rise result in rapid erosion that wipes out any natural regeneration.

South

Florida’s mainland coastline is formed by a narrow to broadband of mangrove

swamp. What was not destroyed by

coastal development in the 1900s forms spectacular forests, 1 to 15 kilometers

in width, along lagoon margins and as the outer coastline on southwest Florida

east and south from Marco Island.

The

red mangrove forests form in the intertidal zone and are the critical coastal

wetland community in assessing the future.

Red mangroves have two important characteristics: over half of their

biomass (living material) is in the subsurface root system; and the forests

with larger red mangrove trees are decimated by major hurricanes.

The

health of the root system depends on the constant replenishment of the rich

organic peat substrate where the roots anchor and feed. Following a hurricane, unless the

damaged site is well flushed by tides, the interior intertidal mangrove

community will not recover but evolve into subtidal ponds and bays. Interior mangrove forests behind

Highland Beach, Big Sable Creek, Gopher Creek, Oyster Bay, and Whitewater Bay

are examples of increasing stages of marine transgression from this

storm-initiated loss.

The

forecast for the next 100 years is not good. An additional 2-3 foot rise in sea level

will lead to massive coastal erosion and interior degradation of our coastal

marshes and mangrove forests.

Dr. Wanless’ Conclusions:

My real concern is that the projected sea level rise

for the next century is one that does not consider the rapid collapse of one of

our frozen water reservoirs. In the past, the rapid steps of sea level rise

were the rule and were mostly the result of collapse (rapid melting) of a portion

of a continental ice sheet. The

dramatic warming projected for this century 2.5F to 10.4F degrees (1.4 to 5.8o

C) will likely trigger the collapse of a portion of the ice sheet of Greenland

or Antarctica, and this will initiate a step of sea level rise well beyond the

consensus projection.

Lagoons and Estuaries.

Rising sea level will increase the tidal zones in

lagoons and estuaries as coastal wetlands are inundated.

The results will be

1.

increased

tidal currents through inlets and openings,

2.

increased

erosion associated with inlets and openings,

3.

increased

transport of sand and mud into lagoons and estuaries,

4.

increased

marine influence within lagoons and estuaries.

Brackish zones will be diminished or shifted further landward resulting in a shift in benthic (submerged bottoms) communities. Adjacent beaches will loose increasing volumes of sand into lagoons and estuaries. Increased depth in lagoons and estuaries will permit increased wave energy and result in increased erosion of shallow sand and mud banks within. Rivers feeding estuaries will deposit their sediment at a more landward position. Higher nutrient and turbidity levels will stress benthic (oysters, clams, crabs, worms, and other invertebrates.) communities.