NYT

1/26/03

At the Beating Heart of an Export Machine

By KEITH BRADSHER

SHENZHEN, China -- THE giant maroon, blue and white cranes here hoist 40-foot-long steel freight containers onto four container ships, each as long as two football fields. The cranes work around the clock, yet lines of trucks bearing containers keep coming, and vessels often crowd a nearby anchorage waiting to be loaded at Yantian port.

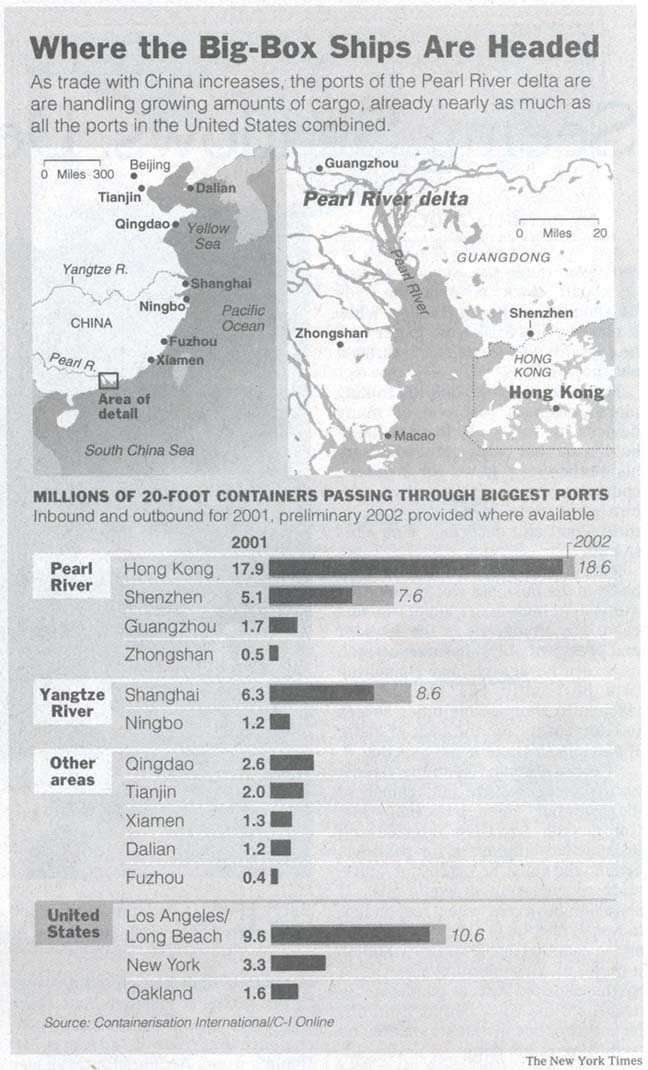

The port, open less than eight years, is just one of a half dozen in the Pearl River delta in southeastern China, including the world's busiest container port, Kwai Chung in nearby Hong Kong. Together these ports now handle almost as many containers as all the ports in the United States combined, and are growing much more swiftly. More than a third of the electronic goods, clothing and other products that flood through here are headed for America.

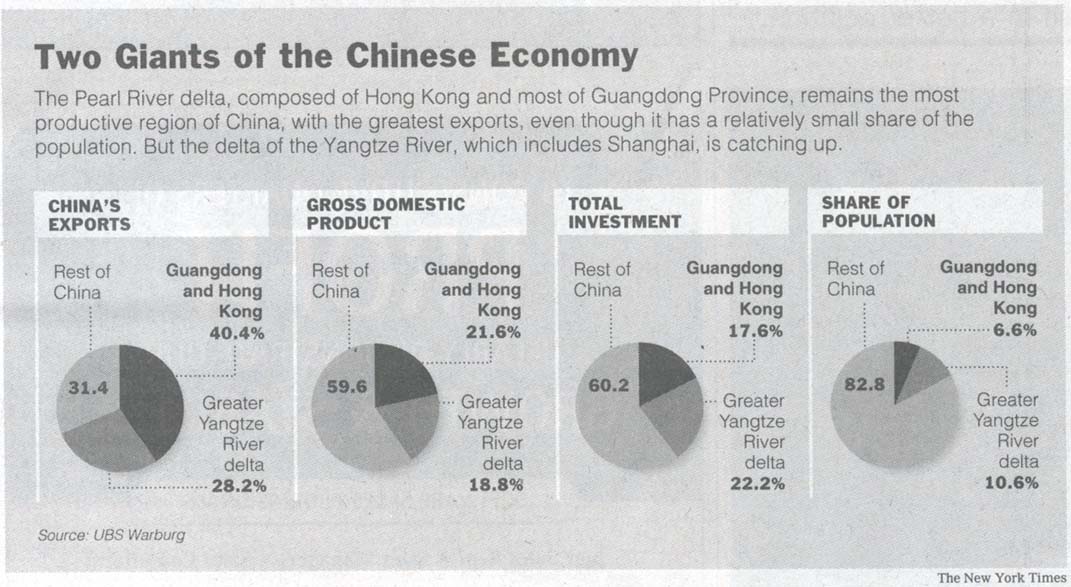

With 3,000 miles of navigable waterways and hundreds of barges that bring containers full of parts right to factories' docks and take away assembled merchandise, the delta is turning into a Venice of manufacturing. The region has led the way in China's extraordinary transformation into a global trading power, producing fully 40 percent of China's exports.

Yet in recent weeks, the delta has also been the scene of an acrimonious struggle over who will control the highways, bridges, tunnels and ports that transport an ever-growing river of goods.

The fight has been pitting some of Asia's wealthiest tycoons, like Sir Gordon Wu and Li Ka-shing, against one another. The tussle is also a contest over the delta's political future, as increasingly assertive municipal governments here and in other cities of Guangdong Province try to seize control of logistics and shipping businesses long controlled by Hong Kong.

The delta region is slightly larger than Connecticut, extending from Hong Kong and Macau, at the mouth of the delta, to Guangzhou, 80 miles upstream, and to Huizhou to the east and Foshan to the west. It exports nearly the same value of goods as all of Mexico or South Korea.

The rising trading power of China — its exports leaped 22 percent last year, and it now trails only the United States, Japan, Germany and France — has been especially important for transportation companies and port operators. Countries that are more developed rely heavily on exports of high-value products that are either small, like computer chips, or that require practically no shipping, like banking and insurance services. But China's ascendancy is in manufactured goods, from shoes and furniture to fax machines and electric fans, and these tend to be bulky products for which shipping and logistics account for a considerable portion of the final price.

EACH city in the delta is now trying to capture as much of this

business as possible by outbuilding its neighbors, often with

wasteful and duplicative results. Five international airports

were built in the late 1990's in a 60-mile radius, and a similar

boom is starting for ports and bridges.

"The Pearl River delta has already become one metropolis," said a recent report from CLSA, the investment bank, and Civic Exchange, a nonprofit research group in Hong Kong. "Administratively, it remains a nightmare with many jurisdictions."

Several Hong Kong developers, led by Sir Gordon, chairman of Hopewell Holdings, want to build a bridge from Macau to Hong Kong's Lantau Island and a new deep-water container terminal port at the western end of it. That would allow factories on the southwest bank of the Pearl River, which lacks deep harbors, to send goods by truck to the new port for loading onto ocean-going ships.

But Shenzhen officials want a tunnel farther up the river, connecting Zhuhai to Shenzhen. That would mean more goods going through Shenzhen's ports. And Guangzhou officials want to build an immense new container terminal farther upstream.

Guangzhou is also replacing its airport with an enormous new one, to compete with Hong Kong's four-year-old airport and recently opened airports in Zhuhai, and is brushing off criticism from Hong Kong that it is all unnecessary. "We are not asking Hong Kong not to develop," Lin Shusen, the mayor of Guangzhou, said recently. "In the same vein, there are some projects that we need to develop, and we hope Hong Kong will not expect us not to."

Even before any construction can begin, trade in the delta will be in for some big changes. On Feb. 2, the United States Customs Service will start levying penalties on any shippers that send containers to the United States without first complying with a 14-item checklist intended to reduce the risk that weapons of mass destruction are concealed inside. The new rules apply to exporters all over the world, but may particularly be a problem here, where exporters take pride in their ability to minimize inventory costs by sending goods to ships hours before sailing time.

Concerns about security rules, port construction plans and other logistics issues are no minor matter here in the delta, where as much as a fifth of Hong Kong's economy depends on the processing of goods for export.

Ports, bridges and tunnels do not just create jobs for dock workers and truckers. Garments and pairs of shoes that cost $2 to make in the delta sell for many times that in the United States, partly because many tasks must be done between the factory gate and the store shelf overseas. These include sorting and inspecting merchandise, packing it into containers, and financing and insuring the goods. Computer printers, VCR's, telephones and other electronic goods are the delta's biggest exports, followed by textiles and apparel, with 36 percent of the shipments going to the United States and 23 percent to the European Union.

The world's largest multilevel industrial building is an immense complex in Hong Kong owned by an American company, the CSX Corporation. The 14-story building at the Kwai Chung docks has 16 miles of roads inside, mostly of three lanes, and handles 10,000 trucks bearing containers each day. Companies like Adidas, Wal-Mart, Target, Next and Liz Claiborne all lease space in the building for various tasks, like inspecting garments.

In one room, lacy white women's vests from the Next brand are loaded into a container in exactly the order they will need to be unloaded at a British department store — eliminating the need for warehouse and sorting space in Britain. Each vest is already on its hanger and has a tag with a price in British pounds.

But packing and loading containers is not cheap. Especially expensive are the handling charges the shipping lines have levied on exporters in recent years. The shippers contend that they are only passing on what they describe as unusually steep fees collected by port operators in China.

In suggesting a new port, Sir Gordon has played on the anger that many exporters here feel at the handling charges, which are highest in the delta. American and European importers, not Chinese exporters here in the delta, typically pay all freight charges except for initial loading fees. Many shippers contend that the port operators form an oligopoly that overcharges the shipping lines for loading containers.

"Hong Kong has got the highest charges of anywhere in the world for terminal charges," Sir Gordon said. "And you know where the second highest is? Yantian, the same management."

The port operators dispute this, especially Hutchison Port Holdings, the world's largest, which manages more than half of Kwai Chung and all of Yantian. John F. Meredith, the company's group managing director, contended that other ports had even higher charges although they used different names for them. He also accused the shipping lines of charging customers much more than they are paying the ports.

"The shipping lines are desperate to get income into their systems, with freight rates so low," he said. Shipping executives deny that they are padding the charges.

HUTCHISON is a subsidiary of Hutchison Whampoa, which in turn

is controlled by Mr. Li, Hong Kong's wealthiest tycoon. Mr. Li

has more than most at stake in the debate over a bridge across

the Pearl River, as he also controls two-thirds of the many shallow-draft

barges with cranes operating on the river. The barges collect

containers up and down the river, then sail to the mouth of the

delta and load the big boxes directly onto ocean-going ships.

Hong Kong's port operators question the insistence of Guangzhou officials that a huge port at Nansha is even feasible. The muddy Pearl River is too shallow to accommodate modern container ships, and shipping lines are planning even bigger vessels.

Guangzhou's plan is an enormous dredging operation to deepen the Pearl River's shipping channel to 48 feet from 30 feet all the way from Nansha to the ocean.

Environmentalists are appalled but have limited influence. Hong Kong port operators say that the port in Buenos Aires has not been able to accept the larger container ships despite continuous dredging, and question whether the Pearl River can ever be deepened.

"When you go up the Pearl River, you're going up one of the world's largest gravel conveyor belts," said William McHugh, CSX's chairman of Asian terminals.

The shallowness of the Pearl River makes it attractive for bridge builders, however. Of all the projects pending, the bridge seems to have the most momentum, having received a strong endorsement on Jan. 8 from Tung Chee-hwa, Hong Kong's chief executive, while provincial officials in Guangdong have toned down some of their objections. "It's one of the most obvious things that should have been built, but because of the lack of coordination over the last 20 or 30 years, it wasn't," said Franklin Lam, a Hong Kong equities analyst at UBS Warburg.

Hanging over every debate about future civil engineering projects, and over the future of the delta itself, is the region's growing competition with Shanghai and the Yangtze River delta.

The Pearl River delta still has a slightly greater economic output and exports. But the Yangtze River delta is attracting more domestic and foreign investment. It is also far ahead in growth industries like heavy manufacturing, computer chip fabrication and financial services that Beijing sees as more important to China's future than the light industry that dominates the Pearl River delta.

Yet the Pearl River delta could have considerable growth ahead. Its southwest bank has less than a quarter of the output of the cities along the northeast bank. Investors have put most of their money into factories within a three-hour drive of Hong Kong — allowing entrepreneurs in chauffeur-driven Mercedeses and BMW's to make the trip to their factories and back in a single day. A bridge from Hong Kong to Macau would open up large areas of farmland for development.

Fully developing the other side of the delta is likely to produce another flood of exports from what is already becoming the world's workshop. "Does that mean double the trade?" asked Michael J. Enright, a business professor at Hong Kong University. "Not necessarily, but not much short of that."