It is not surprising that the first lubki were religious in nature. The escalating cost of time-consuming icons increased the demand for less expensive religious images at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Secular art become popular in Russia later, during the reign of Peter the Great (1682-1725). Printed pictures of saints or events from the Old and New Testaments were given to pilgrims in wealthy monasteries or sold by monks to those who could not afford icons. The early Russian artists of religious prints, Pamva Berynda, Ilia the Monk, and Vasili Koren', were inspired by the Western editions of the Wittenberg Bible (1541), the Piscator Bible (completed in 1650), and the famous woodcuts of Albrecht Dürer, but they altered them by falling back on their own tradition of manuscript illustration and icon painting.

The first center of lubki production was Kiev, in the Ukraine, an area situated between Poland and Russia, and an intermediary through which Western ideas reached Muscovy; it was more cosmopolitan and more open to foreign influences while Moscow, after the foreign invasions and the years of the interregnum during the Times of Trouble (1605-13), remained quite xenophobic. Moreover, the Eastern Orthodox Church in the Ukraine had to contend with Roman Catholicism and the Uniate church, and in the ensuing struggle each side used the prints to advance its cause. In 1980, forty well-preserved early prints were discovered in the Central Historical Archives in the documents of the Holy Synod. Among them was the earliest dated woodcut, The Archangel Michael, which, according to the inscription, was made on October 23, 1668 (Sytova 7). Its composition, as well as compositions of such prints as St. Nicholas or The Holy Trinity, indicates that the printers followed the established canons of icon painting.

The pictures illustrating moral and didactic parables based on the stories from the Bible, for instance The Life of Joseph the Beautiful or The Parable of the Rich Man and Poor Lazarus, show strong affinities with the illustrated manuscripts. Many prints were inspired by the stories from the Great Mirror of Examples (Speculum Magnum Exemplorum). Translated in the late seventeenth century from the Polish, The Great Mirror was a rich mine of morally enlightening topics. It was a source of such prints as The Horrifying Parable, directed against false confession, A Monk's Vision of a Great Flame, a warning against usury and money-grubbing, and Jacob's Story of a Rich Nobleman, a version of the tale from the Golden Legend. In the latter, the Virgin miraculously rescues a woman whose husband promised her to the devil in exchange for helping him become rich again.

Religious prints did not disappear after the reign of Peter the Great, whose decrees and reforms greatly weakened the Russian Orthodox Church, but had to compete with many lubki devoted to satire, information, and everyday life. The religious images could not deliver the necessary excitement and amusement, even though they tried hard to attract believers by illustrating such terrifying and bone-chilling stories as The Temptation of St. Anthony, The Woman of Babylon, or Herod's Massacre of the Innocents. Nevertheless, they continued to supply the market with the basic and always-needed prints like The Assumption of the Virgin and the images of popular saints. The production and distribution of the illustrated moral and didactic parables was assumed by the Old Believer communities where the lubki were not printed but drawn by hand. Scholars indicate the existence of six centers of hand-drawn lubok: Vyg-Leksa Monastery with the adjacent sketes, Ust'-Tsilma, Northern Dvina, Vologda, Guslitsy, and Moscow. These centers produced pictures from the middle of the eighteenth century until the beginning of the twentieth, but their output decreased rapidly after the government closed a number of important Old Believer monasteries in 1854 and 1857. About one-fifth of the topics of the hand-drawn lubok has parallels in the printed lubok. The other topics are original and almost exclusively devoted to religious, moral, and didactic subjects. The quality of the hand-drawn pictures is vastly superior to the printed ones; deriving its strength from the tradition of manuscript illustration and icon painting, each hand-drawn lubok is a true work of art, subtler and more perfect than anything mass-produced. Besides the icon and manuscript painting traditions, the hand-drawn lubok is rooted in the traditions of Russian folklore, particularly in its optimism, love of life, and enjoyment of nature, represented in pictures by fruit-bearing trees, blossoming flowers, and fanciful birds, seemingly more appropriate for illustrating fairy tales than religious parables. Among the subjects of the hand-drawn lubok were portraits of the founders and cenobiarchs of the Vyg-Leksa community (Daniil Vikulov, Andrey and Semyon Denisov), famous patriarchs of the Russian church (Hermogen, Joseph, and Filaret), views of the monastic communities, pictures which compare the attributes of the Divine Service and symbols used by the Old Believers with those used by the official church, and illustrations of historical events or religious texts important to the defenders of the "old faith."

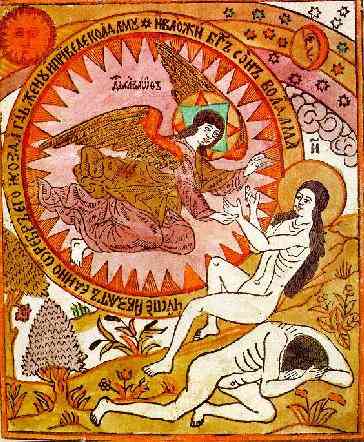

The Massacre of the Participants of the Solovetskii Monastery Uprising by Voivode Meshcherinov, The Parable of the Correct Sign of the Cross, or John Chrysostom's Sermon About the Sign of the Cross are typical of the Old Believers' interests. Also popular were illustrations of traditional Biblical or apocryphal stories, including The Creation of Man, Life of Adam and Eve in Paradise, and the Expulsion, The Sacrifice of Abraham, The Parable of the Prodigal Son, The Story of Esther, and The Story of Cain's Birth, as well as of various short moralizing and didactic texts, well represented by The Spiritual Pharmacy, The Pure Soul, About the Twelve Good Friends, Death of the Righteous and Unrighteous, and The Tree of Useful Advice.

Among the most common images were the representations of the two legendary creatures, Sirin and Alkonost, depicted in Sirin, the Bird of Paradise and Alkonost, the Bird of Paradise. Loosely based on the stories about sirens, these half-women half-birds allegedly lived "in Indian lands" near Eden or around the Euphrates River, and sang their beautiful songs to the saints foretelling them future joys. However, for mortals the birds were dangerous. Hearing their sweet voices, men would forget everything on earth, follow them blindly, and die. To save themselves from the Sirin, people would shoot the cannon, ring the bells and make loud noises to scare the bird off.