"No national culture can be fully understood without such a phenomenon as the folk print" (Alla Sytova, The Lubok, 5).

The lubki (sing. lubok), simple printed pictures colored by hand and often called broadsides, popular prints, folk prints, folk etchings, or folk engravings, are a vivid and fascinating page in the history of Russian culture. Folk prints were known in many other countries (in the Far East as early as the eighth century and in Western Europe from the fifteenth); in Russia they appeared in the middle of the seventeenth century and survived until the beginning of the twentieth. The origins of their Russian name have not been yet clearly determined, but the following four possibilities are usually suggested:

The word lubok may derive from lub, the thin layer of wood under the bark of a mature lime (linden) tree. Lub was only about an inch thick and could not be used for deep carving, but, pressed and dried, served in Old Russia as a popular material for light construction and for writing. Up to the nineteenth century it was common in villages to use the lub panels, covered with ideograms, as boundary markers, debt contracts, and even letters. It is possible that these simple lub images inspired later pictures printed on paper (Danilova 133).

In younger trees, the layer of wood under the bark (bast) was much softer and thinner, but it was also called lub. Since bast was used in Russia for centuries as a material suitable for weaving baskets and shoes and for painting objects made of it with brightly colored designs, some specialists derive the lubok's name from this use.

To make the problem even more complex, in Central Russia, the limewood, soft and easy to carve, and used for making the woodblocks, was also called lub. Perhaps the name of the final product (the print) comes from the name of the material (limewood) itself.

Finally, some lubok scholars suggest that the name derives from the woven bast baskets, since the street hawkers and vendors of the prints carried their wares in such baskets; even today in Russian the woven bast container for berries is called lubianka. Others disagree with this etymology, claiming that the vendors themselves did not call the prints lubki, but used different names, which referred either to the origins and provenance of the prints (friazhskie, suzdal'skie -- from the "West," from Suzdal), to the way they were made (prostoviki -- simple or crude things) or to their themes (bogatyri, konnitsy, prazdniki -- mighty heroes, horseback riders, saints' feasts).

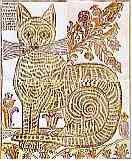

A contemporary viewer is amazed and surprised by the lubok's bold colors, expressive lines, balanced composition, a certain naive simplicity of the drawing, the encyclopedic scope of the topics and the inclusion of large amounts of text in many of the pictures. The specific lubok style is a combination of Russian icon and manuscript painting traditions with the ideas and topics of western European woodcuts. Western prints proved to the Russian artists that print-making was an effective way of disseminating multiple copies of images, and provided them with many subjects and compositions. From icon painting the lubok inherited the tradition of making the most important figures disproportionately large in relation to the others, using no aerial or mathematical perspective but rather a perspective based on multiple points of view, and called, for the lack of a better word, inverted or reversed. Moreover, the unity of time was as easily violated in lubok as in icon composition. One picture often showed several moments of the same story with the hero or heroes appearing in several places. Finally, the lubok was bright and cheerful like many Novgorodian and Northern icons influenced by folklore. The prints were colored with tempera, the paint used by icon painters; but in the print coloring, tempera was thinned out to the consistency of watercolor, which allowed the drawing to show through. The favorite four colors were red, yellow, green, and purple. The earliest prints were pressed from wooden boards. Because the material did not permit the artists to include in their pictures extensive details or large amounts of text, compositions of woodcuts were monumental and clear, uncluttered and expressive. The introduction of copper engraving early in the eighteenth century dramatically extended the ability of the prints to inform, teach, and amuse since the copper plates were a much more precise vehicle to render complex subjects with many figures and many lines of explanatory text. However, in the process of transition from woodblocks to copper plates, the prints lost their compositional clarity, balance of design, and brightness of color. At the same time, the quality of the coloring decreased; dealing with many copies of the same print, the colorists sometimes used broad patches of paint to cover elaborate designs without regard to the outlines and details.

Throughout its relatively brief existence, the lubok responded to the changes in the life of the country and became a popular way of expressing people's feelings about daily events, beliefs, customs, mores, and ideals. It was aptly called "a kind of mirror of the people's soul" (Ovsiannikov 5).

Covering such a great variety of topics, the lubok cannot be divided easily into thematic categories. The greatest collector and cataloguer of the prints, Dmitrii Rovinskii, developed a very detailed classification. According to him, the major categories of lubki were icons and Gospel illustrations; the virtues and evils of women; teaching, alphabets, and numbers; calendars and almanacs; light reading, novels, folktales, and hero legends; stories of the Passion of Christ, the Last Judgement and sufferings of the martyrs; popular recreation including Maslenitsa festivities, puppet comedies, drunkenness, music, dancing, and theatricals; jokes and satires related to Ivan the Terrible and Peter I; satires adopted from foreign sources; folk prayers; and government sponsored pictorial information sheets, including proclamations and news items (after Hilton 110). To facilitate this overview of the rich lubok material, Rovinskii's categories can be condensed into following broader lubok subjects: religion, satire, everyday life, clowns, jesters and fools, information and news, literature, and miscellaneous topics that include astrology, images of animals and birds, advertisements, fortune-telling, and pictures of the world turned upside-down. This classification is not exact; sometimes the borderline dividing the subjects is rather thin.

For instance, The Moneylender's Pleasant Dream can be classified as a satire on loan sharks and pawnbrokers. On the other hand, if one keeps in mind how widespread and common the business of pawning and lending money at high interest had become by the middle of the nineteenth century in Russia (cf. Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment), and if one pays attention to various "realistic"details in the picture, the print can also be considered a scene from everyday life.