The word "icon" derives from the Greek "eikon" and

means an image, any image or representation, but "in the more restricted

sense in which it is generally understood, it means a holy image to which

special veneration is given" (Weitzmann

1978, 7). Even though the word "icon" applies to all kinds of religious

images -- those painted on wooden panels (icons proper), on walls (frescoes),

those fashioned from small glass tesserae (mosaics) or carved in stone,

metal or ivory -- we associate it most often with paintings on wood.

The word "icon" derives from the Greek "eikon" and

means an image, any image or representation, but "in the more restricted

sense in which it is generally understood, it means a holy image to which

special veneration is given" (Weitzmann

1978, 7). Even though the word "icon" applies to all kinds of religious

images -- those painted on wooden panels (icons proper), on walls (frescoes),

those fashioned from small glass tesserae (mosaics) or carved in stone,

metal or ivory -- we associate it most often with paintings on wood.

The first Christian images appeared around the third century. That could be an indication that for the first two hundred years of its existence, the new religion, probably affected by its Jewish roots and the Second Commandment, "Thou shall not make unto thee any graven images" (Exodus 20:4), objected to representational sacred art, particularly to any representation of the Deity. When Christians finally turned to art to aid them in promoting the religion, they found many convertible examples in the earlier art of mystery religions and in the pagan art of the Roman Empire. Naturally, they incorporated various elements from a number of sources: from Hellenic art they borrowed gracefulness and clarity of composition; from the Roman art they took the hierarchical placement of figures and symmetry of design; from Syrian art they took dynamic movements and energy of the represented characters; and from Egyptian funeral portraits they borrowed large almond-shaped eyes, long and thin noses, and small mouths. By the time Christianity became the official religion of the Byzantine Empire (313), the iconography was developing vigorously and the basic compositional schemes were well established.

Even though the representations of holy figures and holy events increased in number, they kept arousing suspicions of traditionalists who inflexibly obeyed the Second Commandment and feared that any deviation from it can lead to heresy or idol worship. Such fears were, at least partially, justified. Not only the average uneducated believer, but often the churchmen themselves could not understand how the three hypostases of God are the One and only God, and how can the divine and human nature of Christ be reconciled.

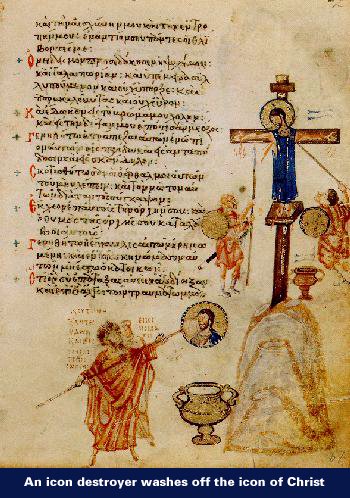

In 726, the Emperor Leo III and a group of overzealous

"puritans" or traditionalists, arguing that misinterpretation of religious images

often leads to

heresy, banned all pictorial representations and began a systematic destruction

of holy images, known as the period of iconoclasm (cf. the scene of whitewashing

the images from the Khludov Psalter). Referring to the decrees of

the Fourth Ecumenical Synod (Council) in Chalcedon (451) which defined

that in Christ the two natures, human and divine, are united without

confusion and without separation, the iconoclasts rejected the images

of Christ because for them they were simply material images which either

confused or separated the two natures of Christ. Such confusion or separation,

in the iconoclasts' opinion, was tantamount to the heresies of Nestorianism,

Arianism or Monophysitism.

In 726, the Emperor Leo III and a group of overzealous

"puritans" or traditionalists, arguing that misinterpretation of religious images

often leads to

heresy, banned all pictorial representations and began a systematic destruction

of holy images, known as the period of iconoclasm (cf. the scene of whitewashing

the images from the Khludov Psalter). Referring to the decrees of

the Fourth Ecumenical Synod (Council) in Chalcedon (451) which defined

that in Christ the two natures, human and divine, are united without

confusion and without separation, the iconoclasts rejected the images

of Christ because for them they were simply material images which either

confused or separated the two natures of Christ. Such confusion or separation,

in the iconoclasts' opinion, was tantamount to the heresies of Nestorianism,

Arianism or Monophysitism.

To fight the iconoclasts, the iconodules (the defenders or lovers of icons) had to find powerful spokesmen who would come up with convincing formulations to prove that icons were not worshipped but venerated and that such veneration was not idolatry. The iconodules based their defense of icons on the Doctrine of the Incarnation and on the Dogma of the Two Natures of Christ. St. John of Damascus (675-749) and St. Theodore of Studios (759-826) wrote extensive treatises explaining the reasons for and the importance of icon veneration. The Damascene argued that "it is not divine beauty which is given form and shape, but the human form which is rendered by the painter's brush. Therefore, if the Son of God became man and appeared in man's nature, why should his image not be made?" The Studite defended the icons on the basis of the ideas of identity and necessity: "Man himself is created after the image and likeness of God; therefore there is something divine in the art of making images. . . As perfect man Christ not only can but must be represented and worshipped in images: let this be denied and Christ's economy of the salvation is virtually destroyed." The iconoclasts, by rejecting all representations of God, failed to take full account of the Incarnation. They fell into a kind of dualism. Regarding matter as a defilement, they wanted a religion freed from all contact with what is material, for they thought that what is spiritual must be non-material. But if we allow no place to Christ's humanity, to his body, we betray the Incarnation and we forget that our body and our soul must be saved and transfigured. Thus, Iconoclasm was not only a controversy about religious art, but about the Incarnation and the salvation of the entire material cosmos. The Empress Irene suspended the iconoclastic persecutions in 780. Seven years later the Seventh Ecumenical Synod in Nicaea reaffirmed the veneration of icons:

"We salute (aspazometha) the form of the venerable and life-giving Cross, and the holy relics of the Saints, and we receive, salute, and kiss the holy and venerable icons. . . These holy and venerable icons we honor (timomen) and salute and honorably venerate (timitikos proskynoumen): namely, the icon of the Incarnation of our great God and Savior Jesus Christ, and of our immaculate Lady and All-Holy Theotokos, . . . also of the incorporeal Angels -- since they appeared to the righteous in the form of men. Also the forms and icons of the divine and most famed Apostles, of the Prophets, who speak of God, of the victorious Martyrs, and of other saints; in order that by their paintings we may be enabled to rise to the remembrance and memory of the prototypes, and may partake in some measure of sanctification. . . To these icons should be given salutation (aspasmos) and honorable reverence (timitiki proskynesis), not indeed the true worship (latreia) of faith, which pertains to the divine nature alone. . . To these also shall be offered incense and lights, in honor of them, according to the ancient pious custom. For the honor which is paid to the icon passes on to that which the icon represents, and he who reveres the icon reveres in it the person who is represented."

However, the attacks on the icons were renewed by Leo the Armenian in 815. Only in 843, during the reign of the Empress Theodora, the iconoclasts were defeated for good; the day of their defeat is celebrated each year on the first Sunday after Lent as Triumph of Orthodoxy.

After the triumph of the icon lovers, iconography developed at an unprecedented speed. By the end of the tenth century most iconographic formulae had been firmly established and had been exported to other Orthodox countries (Bulgaria, Serbia, and a little later, Russia), where they were further developed and elaborated by regional schools. [A.B.]

[Sources: Cavarnos, Ouspensky, Kalokyris].