Vasilii Kandinskii was a painter, a printmaker, a stage designer, a decorative artist, and a theorist. In 1886, he began to study law and economics at the University of Moscow. Three years later, he took part in an ethnographical expedition to the Vologda province and wrote an article about folk art; this experience was to influence his early art, which would be highly decorative and would feature bright colors

contrasting with the dark background. This effective technique can be seen in such paintings as Song of the Volga (1906), Couple Riding (1906), and Colorful Life (1907), devoted to the life of Old Russia. After traveling to St. Petersburg and Paris, in 1893 he was appointed to the Department of Law at the University of Moscow. In 1896, at the age of thirty, he gave up his successful career as a lawyer and economist to become a painter.

He moved to Munich and one year later entered Anton Azbe's painting school. In 1900, he became a student at the Munich Academy and studied under Franz von Stuck. At that time, he was in contact with St. Petersburg

World of Art group. Between 1900 and 1908, Kandinskii exhibited regularly with the Moscow Association of Artists and was very active in the Munich art world. In 1901,

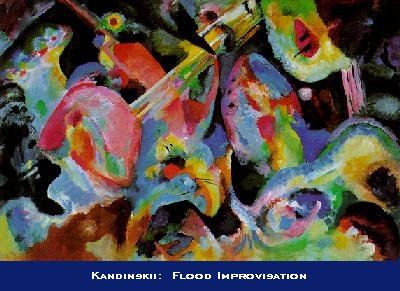

he founded the Phalanx (dissolved in 1904) and began teaching at a private art school in Munich. Later, Kandinskii traveled through Europe (1903-6). He was affected by the expressive possibilities of Bavarian glass painting, icon painting, and Russian folk art. In 1909, the artist started his famous Improvisations and co-founded the group

Neue Kunstlervereinigung. A year later, he joined the Jack of Diamonds group and contributed to its first two exhibitions. In 1911,

the artist established the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) group, which included him, Muenter, Marc, and Kulbin. He participated in its exhibitions and contributed to its

Almanac. The publication of the Almanac was one of the most important events in twentieth-century art. The artists of the

Blue Rider believed in a birth of a new spiritual epoch and were engaged in the creation of symbols for their own time. There were fourteen major articles in the

Almanac, interspersed with notes, quotes, and illustrations. Kandinskii published his concept of "inner necessity." He revised it in 1912, in his famous essay On the Spiritual in Art, Especially in Painting (originally written in German). For Kandinskii, art was a portrayal of spiritual values. All art builds from the spiritual and intellectual life of the twentieth century. While each art form appears to be different externally, their internal properties serve the same inner purpose, of moving and refining the human soul. This belief in the secret correspondence of all the arts would become a cornerstone of

Kandinskii's artistic convictions and a foundation of his painting. The article marked

the artist's transition from objective to non-objective art. In 1914, he returned to Moscow and three years later married Nina Andreevskaia. He was active as a teacher, museum worker, writer, and lecturer, responsible for designing the pedagogical program for the

Institute of Artistic Culture (Inkhuk) for 1920, which included Suprematism, Tatlin's "Culture of Materials," and Kandinskii's own theories. The program was opposed by the future Constructivists and Kandinskii had to wait for its implementation

until his years at the Bauhaus. In 1921, he was actively involved in the organization of Rakhn (Russian Academy of Aesthetics). At the end of the same year, Kandinskii went to Germany to teach at the Bauhaus, where he was to stay

until its closure by the Nazis in 1933. He participated in the Erste Russische Kunstausstellung in Berlin (1922). In 1924, together with Feininger, Iavlenskii, and Klee,

the artist established the Blue Four. He moved to Paris in 1933 and remained active as a painter till his death. (After The Avant-Garde in Russia).

Vasilii Kandinskii was a painter, a printmaker, a stage designer, a decorative artist, and a theorist. In 1886, he began to study law and economics at the University of Moscow. Three years later, he took part in an ethnographical expedition to the Vologda province and wrote an article about folk art; this experience was to influence his early art, which would be highly decorative and would feature bright colors

contrasting with the dark background. This effective technique can be seen in such paintings as Song of the Volga (1906), Couple Riding (1906), and Colorful Life (1907), devoted to the life of Old Russia. After traveling to St. Petersburg and Paris, in 1893 he was appointed to the Department of Law at the University of Moscow. In 1896, at the age of thirty, he gave up his successful career as a lawyer and economist to become a painter.

He moved to Munich and one year later entered Anton Azbe's painting school. In 1900, he became a student at the Munich Academy and studied under Franz von Stuck. At that time, he was in contact with St. Petersburg

World of Art group. Between 1900 and 1908, Kandinskii exhibited regularly with the Moscow Association of Artists and was very active in the Munich art world. In 1901,

he founded the Phalanx (dissolved in 1904) and began teaching at a private art school in Munich. Later, Kandinskii traveled through Europe (1903-6). He was affected by the expressive possibilities of Bavarian glass painting, icon painting, and Russian folk art. In 1909, the artist started his famous Improvisations and co-founded the group

Neue Kunstlervereinigung. A year later, he joined the Jack of Diamonds group and contributed to its first two exhibitions. In 1911,

the artist established the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) group, which included him, Muenter, Marc, and Kulbin. He participated in its exhibitions and contributed to its

Almanac. The publication of the Almanac was one of the most important events in twentieth-century art. The artists of the

Blue Rider believed in a birth of a new spiritual epoch and were engaged in the creation of symbols for their own time. There were fourteen major articles in the

Almanac, interspersed with notes, quotes, and illustrations. Kandinskii published his concept of "inner necessity." He revised it in 1912, in his famous essay On the Spiritual in Art, Especially in Painting (originally written in German). For Kandinskii, art was a portrayal of spiritual values. All art builds from the spiritual and intellectual life of the twentieth century. While each art form appears to be different externally, their internal properties serve the same inner purpose, of moving and refining the human soul. This belief in the secret correspondence of all the arts would become a cornerstone of

Kandinskii's artistic convictions and a foundation of his painting. The article marked

the artist's transition from objective to non-objective art. In 1914, he returned to Moscow and three years later married Nina Andreevskaia. He was active as a teacher, museum worker, writer, and lecturer, responsible for designing the pedagogical program for the

Institute of Artistic Culture (Inkhuk) for 1920, which included Suprematism, Tatlin's "Culture of Materials," and Kandinskii's own theories. The program was opposed by the future Constructivists and Kandinskii had to wait for its implementation

until his years at the Bauhaus. In 1921, he was actively involved in the organization of Rakhn (Russian Academy of Aesthetics). At the end of the same year, Kandinskii went to Germany to teach at the Bauhaus, where he was to stay

until its closure by the Nazis in 1933. He participated in the Erste Russische Kunstausstellung in Berlin (1922). In 1924, together with Feininger, Iavlenskii, and Klee,

the artist established the Blue Four. He moved to Paris in 1933 and remained active as a painter till his death. (After The Avant-Garde in Russia).

In an excellent book on Kandinskii, Hajo Duechting divides the artist's creative development into six periods:

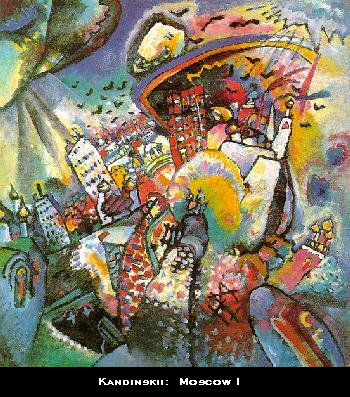

Beginnings: "Mother Moscow" 1866-1896.

Kandinskii was deeply affected by Monet's Haystacks and Wagner's Lohengrin.

Disturbed by the discovery of radioactivity, he believed that art was no longer a means of confronting unbearable tension and disharmony, but rather the exact opposite: it was the only way to adopt a more far-sighted position in the world of contradictions and inconsistency.

Metamorphosis: Munich 1896-1911.

In Germany, Kandinskii developed his idea of the correspondence between a

work of art and the viewer, and called it "Klang" (sound or resonance). He wrote: "Color is the

power which directly influences the soul. Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the

soul is the piano with the strings. The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or

another, to cause vibrations in the soul."

In the same period of artistic development, he began to divide his paintings

into three categories: "Impressions" (which still show some representational elements),

"Improvisations" (which convey spontaneous emotional reactions), and "Compositions" (which are

the ultimate works of art, created only after a long period of preparations and preliminaries.

Characteristically, throughout his life he completed only 10 "Compositions").

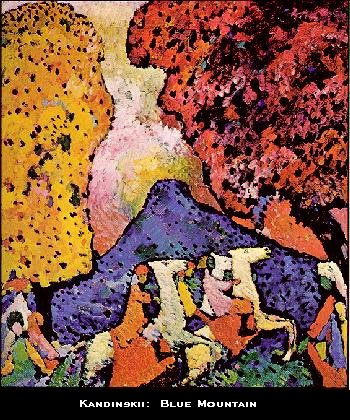

Both, Blue Mountain of (1908) and Improvisation 6 (African)

of 1909 are quite characteristic of Kandinskii's Munich-Murnau period. The earlier painting

includes the motif of riders, particularly important and characteristic for the artist.

The bright dabs of paint are applied thickly over the black background, giving the painting an

almost three-dimensional character; the rendering of the figures actually resembles embroidery.

In the second painting, even though we can still recognize two rudimentary figures, we can no

longer be sure what the figures are doing. The subject is completely subjugated to the vivid,

almost violent color, reminiscent of the Fauves. The forms are more important as carriers of

the colors than carriers of information about the scene. Breakthrough to the Abstract: The Blue Rider 1911-1914.

On the Spiritual in Art included Kandinskii's ideas about the purpose of art. He believed that the nightmare of materialism oppressed the soul of modern man. All the arts, not just painting, were in a state of spiritual renewal and were beginning to come closer to their objective by turning to the abstract, the elemental. But this spiritual renewal could only grow from a complete synthesis of all arts. Until this epoch-making moment arrived, every art form would have to devote itself to an examination of its individual elements. As an example of this, Kandinskii dealt with the psychological effects of color -- one of the fundamental chapters in his theory of art. He formulated a new harmonic theory of tones of color that maintain their tension by means of warm and cold or light and dark contrasts. The new conception of color and form would ultimately result in pure painting: " . . . a mingling of color and form each with its separate existence, but each blended into a common life which is called a picture by the force of the inner need [necessity -- A.B.]." In a series of small steps Kandinskii had discovered a new concept in painting. He had carefully removed the representational elements from his compositions and transferred the subject matter conveyed by these elements to the "distinctive contours" of color and form. In 1910 he had already described the new subject matter of his paintings in the catalogue for the second Society exhibition: "The expression of mystery by means of mystery. Is that not the content? Is that not the conscious or unconscious purpose of the compulsive urge to create?" Russian Intermezzo 1914-1921.

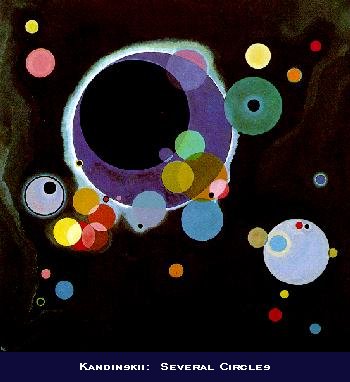

Stylistically, Kandinskii was again coming closer to his early works. Perhaps he wanted to present a hopeful, joyful view of the future, a sort of paradise on Earth such as was promised by the new revolutionary forces. The artist alternated between a tired, abstract idiom, post-Impressionist landscapes, and naive-romantic fantasy pictures. In Kandinskii's work during this period, the turbulent, glaring world of form and color gives way to cool, rational composition based on the stricter analysis of form. He emphatically disassociated himself from his Constructivist critics (especially Puni): "Just because an artist uses 'abstract' methods, it does not mean that he is an 'abstract' artist. It doesn't even mean that he is an artist. Just as there are enough dead triangles (be they white or green), there are just as many dead roosters, dead horses or dead guitars. One can just as easily be a 'realist academic' as an 'abstract academic'. A form without content is not a hand, just an empty glove full of air." Point and Line to Plane: The Bauhaus 1922-1933.

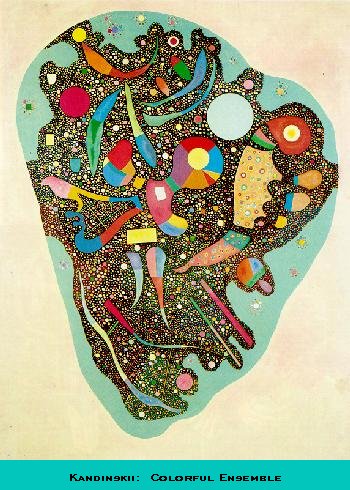

Teaching at the Bauhaus, Kandinskii used the program elaborated for Inkhuk, with certain modifications. In his color theory he stressed the polarity of yellow and blue, black and white, and green and red. Alongside the familiar symbolic classification of colors and their subdivision into "four main tones" -- warm-cold and light-dark, Kandinskii concentrated more on the physical basis of the classification of colors and, above all, explored the color triad of yellow-blue-red. But his teachings about form were essentially new, starting with an analysis of individual elements such as point, line and plane, and examining their relationships to each other. In connection with the growing Constructivist and Suprematist influences at the Bauhaus, individual geometrical elements increasingly entered the foreground of Kandinskii's work. The passionate colors of the Munich and Moscow paintings gave way to to a cool, occasionally disharmonious use of color. The circle -- a symbol of perfect form and a cosmic symbol at the same time -- was the focal point of his paintings of this period. Kandinskii's concept of synthesis remained too closely attached to the romantic idea of a "total work of art" to fit in with the increasingly functional orientation of the Bauhaus. Biomorphic Abstraction: Paris 1934-1944.

The most conspicuous transformation in the late paintings of Kandinskii was the use of most subtly differentiated nuances of color. He seems to have left at the Bauhaus all the constructivist color theories, based on primary and secondary colors. He started using combinations of colors never before seen in the world of art; most of them had a delicate filigree effect and were reminiscent of the Slavic folk art. The colors were applied thinly, sometimes transparently, so that they produced an added blending effect. He also used sand to achieve a different texture. As if this new use of color was not enough, Kandinskii dissolved the basic geometric forms into an unbelievable variety of shapes, among which biomorphic ones predominated. These new forms were inspired by a variety of sources, from invertebrate sea creatures, microorganisms and zoological prototypes, to the embryological forms. The paintings of this period are hot-headed, seething, primaeval, as if some distant sun were trying to set life flowing again with protoplasm in a pond. In order to divorce himself from "abstract" Surrealism, Kandinskii redefined the idea of "concrete" art for his own purposes: "Abstract art places a new world, which on the surface has nothing to do with 'reality,' next to the 'real' world. Deeper down, it is subject to the common laws of the 'cosmic world.' And so a 'new world of art' is juxtaposed to the 'world of nature.' This 'world of art' is just as real, just as concrete. For this reason I prefer to call so-called 'abstract' art 'concrete' art."

Kandinskii introduced a completely new conception of painting that he bequeathed to us in a variety of modes which were often received with hostility. It is a model of art that is non-representational, but understandable in substance. Very different artists and artistic trends have branched out from this model. But the resources of Kandinskii's ideas and theories have not yet been exhausted. (Adapted from Duechting). [K.T. and A.B.] [Sources: Duechting, O'Neill, The Avant-Garde in Russia].