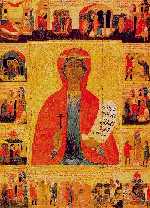

Novgorodian School icons: From top to bottom and from left to right: Saints John Climacos, George, and Blaise (last third of the 13th c.), The Prophet Elijah (late 14th c.), Saints Florus and Laurus (late 15th c.), Saints Blaise and Spiridonos (late 14th c.), Paternitas (The New Testament Trinity) (late 14th c.), The Intercession of the Virgin (end of the 14th-beginning of the 15th c.), The Birth of the Virgin (middle of the 14th c.), St. Nicholas, with Scenes from His Life (fist half of the 16th c.), Saints Nicholas, Blaise, Florus, Laurus, Elijah and Paraskeva (first half of the 15th c.), St. Paraskeva, with Scenes from Her Life (first half of the 16th c.). The last icon is often considered a work of the Tver school.

Novgorod has always been a very important Russian city. Once a prosperous mercantile community, it kept its independence until 1478, when it succumbed to Moscow. Before that year, it distinguished itself for its economic, social, political and artistic achievements. As early as the10th century, it became the cradle for new political ideas. Novgorod was a republic (it called itself Lord Novgorod the Great), governed by the veche, a democratic assembly of all citizens, roughly resembling a parliament. The citizens were called to special meetings by the veche bell; the participants made their decisions together. The Novgorodians rejected the idea of the princely rule; instead, they hired a prince when they needed a leader to help them fight their enemies. When the danger was over, the prince was dismissed and asked to leave the city. The princes' names had been often linked with the building of the most famous churches and cathedrals: Cathedral of St. Sophia (1045- 1050), the Nikolo-Dvorishchensky Cathedral (1113) and the Cathedral of Saint George in the Yuriev Monastery (1119).

Not many Novgorodian 11th-century paintings have survived, but the surviving works of the 12th century (sometimes only fragments) help prove the existence of an independent local painting tradition. The frescoes at Nereditsa and in the Church of St. George at Staraia Ladoga are the evidence of this kind. Icons from the same period display a very strong Greek influence even though they show a very characteristic Russian style at the same time. In the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries, Novgorod produced some of the greatest works of medieval Russian art, best represented by the paintings of Theophanes the Greek (Feofan Grek). In some of his greatest works it is possible to find the combination of the local style with the style of Constantinople, where he worked before coming to Russia. Most notable are his frescoes in the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street (1378), the icon of the Virgin of the Don, The Dormition of the Virgin, and The Transfiguration. Later, Theophanes moved to Moscow and contributed to the development of the Moscow School, particularly by working together with Andrei Rublev and other Moscow masters.

Icons represent Novgorodian art better than any other artistic genre . Their style, which developed through the centuries, was probably based not only on "imported" Byzantine examples but on the existing tradition of popular folk art. Early icons are conventional but reflect the spiritual strength and beauty of man. They are simple, laconic and precise; the compositions are based on contrast between large shapes, the colors are saturated and bright, and the drawing is energetic. In the 12th and 13th centuries an emphasis is put on contrasting colors and simplicity of the image. Among the saints most beloved and popular in Novgorod are Saint Nicholas, St. George, Elijah, Paraskeva Piatnitsa (the Holy Friday), Florus and Laurus, and Cosmas and Damianos. Most of these saints were particularly venerated because their celebrations fell on the days important for the peasant's agricultural calendar or because they were connected to the ancient Slavic pagan gods (Saint Nicholas to Veles, St. George to Dazhbog, Elijah to Perun, Paraskeva to Mokosh, and Cosmas and Damianos to Svarog).

Some of the most important features of the mature Novgorodian style of icon painting include:

brightness of colors;

increased complexity as compared to Kievan and early (10th-13th century) Novgorodian icons;

increased liveliness characteristic of their developing "anecdotal style" (Hamilton, 153);

"graphic" quality (emphasis on drawing and line).

The late 13th and early 14th century feature a change in style and the introduction of more monumental, flat, graphic qualities together with relative depth of form. The dominant colors are cinnabar, white, ochre, brown and green. The 14th century, a period of great prosperity for Novgorod, is reflected in a proliferation of Novgorodian icons. The period that follows marks another stylistic change: the 15th-century palette becomes remarkably lighter and the compositions are more dynamic and mobile. Moreover, a precise canonical system for the arrangement of icons in the iconostasis wall is finally established. At the end of the 15th century Novgorodian art begins to decline as a result of Moscow's political dominance and the influence of the art of such great Moscow painters as Daniil Chornyi (Daniel the Black), Prokhor of Gorodets, Andrei Rublev, and Dionisii(Dionysius). [S.C. and A.B.]