Il'ia Efimovich Repin was born in Chuguev, in the Ukraine, in the family of a soldier-settler. He received his first lessons in art in 1858, when he started working for I. M. Bunakov, a talented icon painter from Chuguev. Commissions for portraits and religious paintings allowed Repin to collect enough money to go to St. Petersburg with the goal of entering the Academy of Arts. He arrived in the capital in 1863 and enrolled in the School of Drawing attached to the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts. Working with Kramskoi, in a year the young artist developed his skills sufficiently to be accepted to the Academy. In May 1870 Repin went on a boat trip down the Volga during which he made sketches for his Barge-haulers on the Volga (The Volga Boatmen). A year later the artist finished his schooling at the Academy. His graduation work, The Resurrection of Jairus' Daughter, won the Gold Medal and a six-year scholarship (including three years of travel abroad). After traveling through Europe and staying in Paris (1872-76), Repin returned to Russia. He spent a year in Chuguev, making sketches for his famous Religious Procession in the Kursk Province. The next six years (1876-82) Repin lived in Moscow, trying to get along with the Academy, the Mamontov circle, and his old friends Stasov and Kramskoi. Tired of their constant squabbles, he moved to St. Petersburg. He made several more trips to Europe -- in 1883, 89, 94, and 1900. He taught at the St. Petersburg Academy (1894-1907) and was an influential member of the

Wanderers. In 1900, during a trip to Paris, Repin met Natalia Nordman, the "love of his life" (Repin was separated from his wife), and moved to her home,

Penaty (Penates), in Kuokkala (Finland), located about an hour's train ride from St. Petersburg. Together, they organized the famous Wednesdays at the

Penaty which attracted the creative elite of Russia. When Nordman died in 1914, she left the estate to the Academy, but Repin occupied it for the next sixteen years. Handicapped by the atrophy of his right hand, Repin could not produce works of the same quality as those, which brought him fame. Although he trained himself to paint with his left hand, he lived his last years under a constant financial strain. Since the artist did not accept the Revolution of 1917, he did not want to go back to Russia, even though In 1926 a delegation sent by the Ministry of Education of the Soviet Union helped him financially and tried to entice him to return. To acknowledge and commemorate Repin's artistic achievement, in 1948 Kuokkala was renamed Repino.

Il'ia Efimovich Repin was born in Chuguev, in the Ukraine, in the family of a soldier-settler. He received his first lessons in art in 1858, when he started working for I. M. Bunakov, a talented icon painter from Chuguev. Commissions for portraits and religious paintings allowed Repin to collect enough money to go to St. Petersburg with the goal of entering the Academy of Arts. He arrived in the capital in 1863 and enrolled in the School of Drawing attached to the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts. Working with Kramskoi, in a year the young artist developed his skills sufficiently to be accepted to the Academy. In May 1870 Repin went on a boat trip down the Volga during which he made sketches for his Barge-haulers on the Volga (The Volga Boatmen). A year later the artist finished his schooling at the Academy. His graduation work, The Resurrection of Jairus' Daughter, won the Gold Medal and a six-year scholarship (including three years of travel abroad). After traveling through Europe and staying in Paris (1872-76), Repin returned to Russia. He spent a year in Chuguev, making sketches for his famous Religious Procession in the Kursk Province. The next six years (1876-82) Repin lived in Moscow, trying to get along with the Academy, the Mamontov circle, and his old friends Stasov and Kramskoi. Tired of their constant squabbles, he moved to St. Petersburg. He made several more trips to Europe -- in 1883, 89, 94, and 1900. He taught at the St. Petersburg Academy (1894-1907) and was an influential member of the

Wanderers. In 1900, during a trip to Paris, Repin met Natalia Nordman, the "love of his life" (Repin was separated from his wife), and moved to her home,

Penaty (Penates), in Kuokkala (Finland), located about an hour's train ride from St. Petersburg. Together, they organized the famous Wednesdays at the

Penaty which attracted the creative elite of Russia. When Nordman died in 1914, she left the estate to the Academy, but Repin occupied it for the next sixteen years. Handicapped by the atrophy of his right hand, Repin could not produce works of the same quality as those, which brought him fame. Although he trained himself to paint with his left hand, he lived his last years under a constant financial strain. Since the artist did not accept the Revolution of 1917, he did not want to go back to Russia, even though In 1926 a delegation sent by the Ministry of Education of the Soviet Union helped him financially and tried to entice him to return. To acknowledge and commemorate Repin's artistic achievement, in 1948 Kuokkala was renamed Repino.

As Fan and Stephen Jan Parker note in their monograph on Repin, "Western art historians and critics have minimized Repin's achievements and contributions either because his very "national" identity has not been grasped, or because -- and this is most likely -- Repin was neither a technical innovator nor the creator of a school of painting. Moreover, he was a realist and not a modernist. Yet in the esteem of both prerevolutionary and Soviet Russia, Repin occupies a position alongside Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov. He was and is Russia's foremost national artist, whose oeuvre adheres to the requisities for national art as proposed by the noted painter and art historian Igor Grabar: it must reflect the spirit of the people, expressing their thoughts and aspirations; it must excite; and it must be understandable to the people" (Parker, 1).

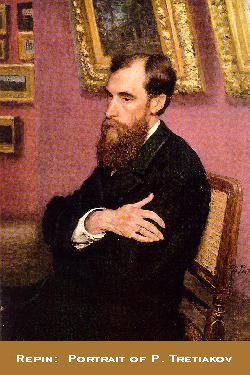

Among Repin's most famous canvasses are The Volga Boatmen (1872), The Archdeacon (1877), Portrait of the Composer Musorgskii (1881), Religious Procession in the Kursk Province (1878-83), Portrait of Pavel Tret'iakov (1883), They Did Not Expect Him (1884), Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan: November 16, 1581 (1885), and Zaporozh'e Cossacks Writing a Reply to the Turkish Sultan (1880-91).

The Volga Boatmen was enthusiastically received. Stasov predicted fame and success for the young artist and Dostoevskii wrote the following review in his Writer's Diary:

"As soon as I read in the newspapers about the burlaki of Mr. Repin, I immediately became frightened. The very subject is horrible: we are conditioned to believe that the burlaki more than others are capable of conveying the well-known socialist idea about the unpaid debt of the privileged class to the people. In expectation of this I was prepared to meet them all in uniforms with appropriate labels on their foreheads. What happened then? To my joy all my fears turned out to be in vain. Not one of them shouts to the viewer from the painting: 'Look how miserable I am and how great a debt you owe to your people!' Just for this alone the artist deserves the greatest merit. Good, familiar figures: the two front burlaki are almost laughing, at least they aren't crying at all, and by no means are they thinking about their social condition . . ." (after Parker, 26) [K.T. and A.B.].

[Sources: Parker, Zotov, Klimov, Hamilton].