Centuries of Sugar: St. Kitts Heritage and Identity

Interpretative Essay

Dr. Grant H. Cornwell

College of Wooster

Columbus brought sugar cane to the New World in 1493, on his second voyage. On that same voyage, he sailed by the island we now know as St. Kitts, and claimed it for Spain without ever landing. Of course, as with many other islands of the Caribbean, there was a thriving population of indigenous people living there at the time. They called the island "Liamuiga" which describes it as a place of fertile lands and abundant water.

It is important to understand that the conquest, displacement, and genocide of the Caribbean's indigenous populations, and the subsequent peopling of the region with Europeans, Africans, and later Asians, was always about amassing wealth for Europe. Though the original quest was for gold, the value of the Caribbean colonies for the European powers that fought over them for centuries derived from plantation agriculture.

The history of St. Kitts is unusual in that its colonization was a shared enterprise between the French and the English. In 1626, the settlers from these two colonial powers cooperated to massacre the entire population of indigenous people, and subsequently divided the island between them. The first cash crops were tobacco and cotton, but since 1648 St. Kitts has been an island exclusively devoted to sugar cane.

Why sugar? What is it about this commodity that made it so important to the colonial project? Consider the impact. The labor demands for sugar production were the primary economic motive for the African slave trade, that heinous human institution refined in colonial Europe that violently stole 20-30 million souls from Africa between the mid-1600's and the mid-1800's. The wealth generated by the sugar industry in the colonial era essentially provided the incentive and the funding for the Industrial Revolution, a time when Europe consolidated its global dominance. The triangular trade between Europe, which exported manufactured goods, Africa, and the Colonies was the prototype of modern global capitalism. What is it about sugar that makes it so important?

Sugar is such a ubiquitous element of our diet today that it is difficult to grasp that it was essentially unknown in Europe much before 1300; at that time it was a precious spice, thought also to have medicinal properties, and available only to wealthy aristocracy. It actually entered the British diet as a sweetener for other colonial commodities - tea, coffee, chocolate- in the 18th Century, and as these commodities became more plentiful, and therefore cheaper, and therefore more available to the middle and lower classes, the demand increased for sugar. When globalization is talked about as a contemporary phenomenon, it is important to realize that tea with sugar, that beverage that defines Britishness, was firmly established as the national beverage in the 18th Century. A commentator in 1795 remarks "After all, it appears a very strange thing, that the common people of any European nation should be obliged to use, as part of their daily diet, two articles imported from opposite sides of the earth" (Davies). Strange perhaps, but also telling; tea from the East Indies combined with sugar from the West Indies was a toast made three times a day to Europe's possession of the globe as its colonial plantation.

Sugar penetrated the European diet with tremendous success. Consider these figures on the British per-capita consumption of sugar per year:

| Year | Amount Consumed per Person |

|---|---|

| 1700 | 4 lbs. |

| 1750 | 10 lbs. |

| 1800 | 18 lbs. |

| 1850 | 50 lbs. |

| 1900 | 90 lbs. |

By the end of the 19th Century, sugar accounted for 20% of caloric intake in the British diet; in 200 years a commodity had gone from being rare and precious, unknown to most, to being a staple in the British diet (Mintz).

St. Kitts is sometimes called "the Mother Colony" because it was the center of the British sugar trade in the West Indies for much of its colonial history. It has a venerable reputation for producing very high quality sugar, and its yields - that is, the tons of sugar produced per tons of cane harvested - have always been among the highest anywhere. The fertile volcanic soils and the ample rainfall together distinguish St. Kitts among Caribbean islands. This is not to say that growing sugar on St. Kitts was ever easy or always profitable.

In the 15th Century, the Spanish and Portuguese developed the model of sugar plantations using African slave labor in the Atlantic islands of the Canaries, the Azores, and the Madeiras. While they brought this model with them to the New World, it was really the English, French, and Dutch who reproduced it throughout the Caribbean. Its basic structure remained essentially unchanged for centuries. All arable land, however marginal, however steep, was cleared and cultivated. Sugar islands, of which St. Kitts is a paradigmatic example, were divided into estates, typically around 300 acres in size. A compound of buildings would be found strategically located on each estate and this hub of activity served as the organizational, industrial, and command center of the plantation. Each would have carefully sited residences, where size and situation were dictated by rank, for the planter, the estate manager, and the estate overseer. Slave villages, built by the slaves without material support from the planter, were situated in nearby gullies, land unfit for growing. Also in the "yard" you would find a mill for crushing the harvested cane, a boiling house for processing the cane juice into raw sugar, a warehouse where barrels of sugar sat while the molasses drained from them, and stables for the draft animals.

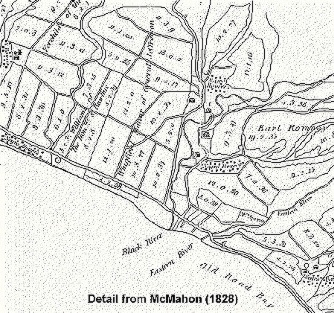

Sample of McMahon map made in 1828 showing sugar estate boundaries, location of mills, factories, and "Negro Villages."

Sugar was first domesticated in New Guinea in around 10,000 BC, and first processed into a form we would recognize in India around 500 AD. Sugar is planted by laying short pieces of cane horizontally in shallow trenches. Sprouts emerge from the eyes of the cane stalks and mature to a height of 10-15 feet in a period of 14-18 months. Harvested fields will regenerate on their own several times before a field has to be replanted. These "rattoon" fields saved labor and were resistant to drought since the root structure was already established. But with each subsequent harvest, the yield from rattoon fields goes down. For all of its colonial history, and still today to a remarkable extent, the planting, manuring, weeding, and harvesting of the cane are done by hand.

Growing sugar requires very strenuous physical labor at every step, and this labor was strictly organized on the estates. The rule of thumb was that a 300-acre plantation would require 300 slaves to labor on it. By 1650, St. Kitts was entirely devoted to sugar production; cleared lands were under cultivation and forest clearing was progressing as fast as available labor would allow. What this meant was that the planters of St. Kitts had an inexhaustible commercial desire for as many slaves as they could acquire. By 1680, the population of St. Kitts numbered roughly 1,500 whites and an equal number of slaves. By 1720, there were 2,740 whites and 7,321 slaves. In the following decade, St. Kitts planters imported over 10,000 slaves, though the population increased by only 7,000, a clear indication of the death rate among the slave population. In the 1730's the number of whites in St. Kitts began to decline, and continued to do so over the next century as planters who made their fortunes moved back to England and managed their estates as absentee landlords. Through this era the population hovered at around 2000 whites and 20,000 slaves, at a ratio of 1:10.

The first task in establishing a plantation was creating fields out of tropical forest. Since every estate sought constantly to expand its acres under cultivation, this is a task that went on for well over a century on St. Kitts. This task, being the most grueling, fell to the slaves newly arrived from Africa. This lowest rung on the estate hierarchy also had the highest mortality rate. Weakened from "the Middle Passage" from Africa to the Caribbean, having been chained in the holds of ships for weeks with inadequate food, water, and sanitation, these traumatized captives were forced by whip to clear tropical forest all day, every day, from the moment they arrived.

Field slaves were organized into "gangs" of 10-15, each controlled by an overseer. The most highly skilled of the field slaves were the cane cutters, as yield depended upon cutters who knew how to wield a machete so as to cut the cane close to the ground, where the concentration of sucrose was highest, and leave the cane tops in the field to replenish and protect the soil. Haulers would collect the cut cane and transport it to the mill by an animal cart if the terrain allowed, by hand otherwise.

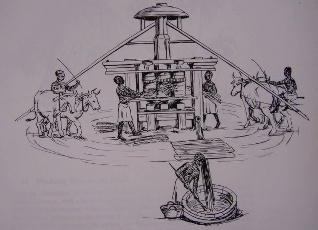

The most highly skilled plantation tasks were in the "yard" where the crushing and processing took place. When cane was cut, its juices had to be extracted within 24 hours or they would begin to sour. In every epoch, this extraction took place by crushing the cane stalks between massive rollers; what evolved was the technology for powering the rollers. Early sugar mills throughout the Caribbean used animal traction. Rollers were turned by a variety of draft animals, circumambulating a central post to which they were harnessed.

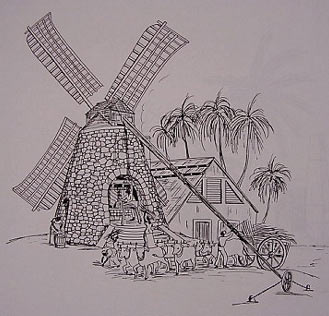

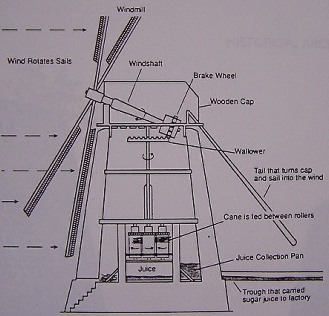

Animal traction was reliable but slow. The profitability of estates depended upon economies of scale, and the more quickly the cane could be crushed, the more sugar an estate could produce. ![]() The Dutch windmill was the standard of the sugar industry for over 200 years. Owing to the trade winds of the Caribbean, windmills were fast, powerful, and sufficiently reliable. At the height of St. Kitts' colonial sugar industry there were over 300 windmills operating on the island. Because the landmass was carved up into estates, and because the mill had to be located in the center of the estate, the visual effect was to create an entire island landscape evenly dotted with stone towers. The towers, of course, had to be built, and this created another hierarchy of slave labor. In the months when cane was not being harvested, estates would turn their labor toward building the infrastructure. Because wood rapidly ran out, because labor was available, and because stone construction could withstand the regular hurricanes, mills, factories, and greathouses were built of cut stone. Paralleling the labor organization of sugar, some gangs of slaves were set to the task of hewing rough stone out of the quarries, others to the task of hauling the stone, and others to the technically challenging task of hand-cutting uniform blocks. A stone cutter could produce about eight building blocks in a day's work. When one considers the mills and factories on 300 estate yards, and how many stones go into each structure, one begins to comprehend the scale of slave labor used to power the sugar industry.

The Dutch windmill was the standard of the sugar industry for over 200 years. Owing to the trade winds of the Caribbean, windmills were fast, powerful, and sufficiently reliable. At the height of St. Kitts' colonial sugar industry there were over 300 windmills operating on the island. Because the landmass was carved up into estates, and because the mill had to be located in the center of the estate, the visual effect was to create an entire island landscape evenly dotted with stone towers. The towers, of course, had to be built, and this created another hierarchy of slave labor. In the months when cane was not being harvested, estates would turn their labor toward building the infrastructure. Because wood rapidly ran out, because labor was available, and because stone construction could withstand the regular hurricanes, mills, factories, and greathouses were built of cut stone. Paralleling the labor organization of sugar, some gangs of slaves were set to the task of hewing rough stone out of the quarries, others to the task of hauling the stone, and others to the technically challenging task of hand-cutting uniform blocks. A stone cutter could produce about eight building blocks in a day's work. When one considers the mills and factories on 300 estate yards, and how many stones go into each structure, one begins to comprehend the scale of slave labor used to power the sugar industry.

Windmills were stone towers roughly 30 feet tall, conical in shape. They are massive structures with walls three feet thick, necessary to support the strain of the huge blades rotating in the wind. They had a wooden cap, that could be swiveled by a large boom to face the day's wind, that housed the support for the huge sail blades and the gears for converting the spinning sails into a rotating shaft. This shaft, in turn, powered the crushing rollers, vertically arranged on a massive pedestal inside the base of the mill. Field gangs would deliver loads of cane by cart to the mills entrance where two men would feed the stalks into the rotating crushers. There was no stopping the mill. This was profoundly dangerous work; on the wall of each mill hung an ax to chop off the arm of a slave who got caught in the crushers. The cane juice would collect beneath the rollers and travel via a sluice to the boiling house position nearby and downhill. The crushed cane, called bagasse, was collected to fuel the fires in the boiling house.

|

|

from Gosner | from Goodwin |

|

|

Betty's Hope Restoration Project, Antigua | Betty's Hope Sugar Mill |

Late in the 18th Century steam driven mills replaced windmills on most estates in St. Kitts. And thus, as one surveys the landscape, the typical view will show a stone smokestack as a taller twin to the older windmills.

Cane juice had to go through a careful process of boiling and refining to enable crystals to form. Boiled first in a large iron kettle, called a "copper", the juice had to be manually ladled from one copper to the next down a chain of three to five, each at the right time to secure the maximum yield, the maximum purity. Though laboring over blazing kettles in tropical heat was brutal work, Boilers were the most technically skilled, and thus respected, slaves on an estate. When the time was right, the cane syrup from the last kettle would be poured into a cooling pan and then packed into huge barrels called "hogsheads." These, in turn, would be moved into the warehouse where they would be arranged on beams suspended over a catchment that would collect the molasses as it drained from the sugar. This molasses was subsequently used to feed the livestock and to make rum in a distillery attached to most factories.

|

|

Sometimes today the life imagined on a colonial plantation is overly romanticized. First, it is a myth that all of the planters were wealthy or that any planter was always wealthy. Sugar was more of a boom and bust industry owing to the vagaries of drought and hurricanes, but even more to the widely fluctuating price paid for sugar. It is true that many planters endeavored to mimic the social norms of the highest aristocracy in Europe. They would decorate their greathouses with fine furniture, much of which was made of tropical hardwoods by local slave craftsmen. And many accounts of the time give testimony to the fact that the latest fashions would arrive from Europe as often as every six weeks. But making a go of a plantation was a risky undertaking and many failed. Over the years, estates became concentrated in fewer and fewer hands; they retained their names, their spatial and social organization, but their ownership collapsed into an elite plantocracy that controlled most of the island. And most of these owners were absentee, often leaving or sending one of their offspring to manage affairs on the island.

It is also important to realize that in place of the colonial fantasy of gentility, tranquility, and luxury, the social atmosphere of St. Kitts was shot through with the brutality and violence of the regimes of slavery. Slavery was never an acceptable institution to slaves and they resisted constantly and in a myriad of ways. Slow work, breaking machinery, stealing whatever they could to try to stay alive, and of course, running away, were all strategies well known and practiced. The mountains of St. Kitts, like the more famous Blue Mountains of Jamaica, became havens for communities of runaways known as "maroons". "Markus, King of the Woods" is a local folk hero; a maroon leader in the 1830's, he led a band that harassed and pillaged estates for years. The response to all forms of resistance was a system of brutal punishments calibrated to each offense, from whippings to the severing of limbs to death by various tortures. A society with this kind of conflict and violence creating the context for every social relation was never one of peace and harmony.

In the British Caribbean, slavery was abolished as a legal institution in 1834, but the material realities of island life meant that things changed very little for the vast majority of the population, white and black. White planters owned all land, controlled all employment, and controlled the government. St. Kitts remained a society where all social and economic life was organized around the sugar estates. Indeed, it is arguable that this pattern persisted until very recently. In the early 1900's the cane sugar industry was in a global crisis. The introduction of beet sugar had taken away much of the market and global over-production had reduced the price to a point where the estates of St. Kitts were all struggling. Faced with this, the estate owners of St. Kitts embarked on a plan to modernize their techniques by building a central sugar factory, thus abandoning their antiquated and inefficient estate factories, and to build a railway around the island to transport the sugar to the factory. This move, together with the changes in market and demand brought about by World War I, brought St. Kitts sugar back into profitability for a time.

However, in the 1970's the industry was again in crisis. The private estates were so economically fragile that they could not secure loans without government backing. At this point the government launched the "Sugar Rescue Operation" which brought about a profound change in the economic and social relations on St. Kitts. Though the story is a complicated one, the government nationalized all sugar lands on St. Kitts and bought the central factory. This move was vigorously protested by the estate owners, in truth for many of them, not so much because they resisted the state's strategy of taking over sugar production, but because the price offered by the state for the cane lands was dramatically lower than what the estate owners wanted to be paid. The matter was wrestled in court for many years, and repeatedly the courts found the government's actions unconstitutional. Nevertheless, the government persisted, and to this day all sugar grown and processed on St. Kitts is done by the St. Kitts Sugar Manufacturing Company, a state-owned enterprise.

While this profound reorganization did return sugar to profitability for a time, we are right now in the midst of the protracted death of the industry on St. Kitts. In the year 2000, it cost $2,440 to produce a ton of sugar on St. Kitts that had an average selling price of $997 a ton. In that year, St. Kitts produced around 18,000 tons of sugar that brought in just over $24 million in earnings; however, it cost the industry over $56 million to bring in that harvest. This loss has been accruing at an increasing rate for many years, and the industry stands in debt of over $180 million (Bacchus).

Why is this the case? With rich soils, ideal weather, and centuries of accumulated wisdom about growing sugar, how can it be that the industry cannot turn a profit? The answers are complex. First, St. Kitts competes with other sugar growing nations that have massive modern industries and huge tracts of land where cane can be planted and harvested by machines. Because of the topography of St. Kitts, 80% of the cane is still cut by hand, and labor costs on St. Kitts are much higher than in other sugar producing nations. Second, the sugar infrastructure on St. Kitts is antiquated and there are no scenarios that suggest that recapitalizing the industry is rational. Finally, St. Kitts sells almost all of its sugar to the United Kingdom, and the remainder to the United States, at preferred prices up to four times the world market, and losses are still skyrocketing. These protected trade agreements are under negative pressure in an era of "free trade" and the World Trade Organization, and do not have a future.

The consequence is that we are witnessing a profound moment in the history of St. Kitts. A society that has been built around the growing and processing of sugar cane for 350 years is on the brink of an identity crisis. What will come of it is a question on the minds of everyone from government officials to field workers. There are many plans being discussed, but almost certainly the heritage of the people of St. Kitts, and their long history with sugar, must be a topic central to any plan.

This digital photo essay is dedicated to the people of St. Kitts in hopes that in some way it might contribute to protecting the integrity of the heritage of St. Kitts and respecting the dignity of those who have inherited it.

Sources

- Bacchus, Clive. "Sugar Decision Likely Next Month." The St. Kitts-Nevis Observer. No 34, May 11-17, 2001.

- Dyde, Brian. St. Kitts: Cradle of the Caribbean. Macmillan Education LTD, London. 1999.

- Farara, James. "Crisis and Response: The Dynamics of Sugar Production in St. Kitts." Dissertation. Christ Church, Oxford. 1990.

- Goodwin, Conrad. "Betty's Hope Windmill: And Unexpected Problem." Historical Archaeology. 28:1. 1994.

- Gosner, Pamela. Caribbean Georgian: The Great and Small Houses of the West Indies. Three Continents Press, Washington DC.

- Merrill, Gordon. The Historical Geography of St. Kitts and Nevis. Instituto Pan Americano de Geografia, Mexico City. 1958.

- Mintz, Sidney. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. Penguin Books, New York. 1986.

- Richardson, Bonham. Caribbean Migrants: Environment and Survival on St. Kitts and Nevis. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville. 1983.