Niels Bohr's letter

Dear Heisenberg,

I have seen a book, “Stærkere end tusind sole” [“Brighter than a thousand suns”] by Robert Jungk, recently published in Danish, and I think that I owe it to you to tell you that I am greatly amazed to see how much your memory has deceived you in your letter to the author of the book, excerpts of which are printed in the Danish edition [1957].

Personally, I remember every word of our conversations, which took place on a background of extreme sorrow and tension for us here in Denmark. In particular, it made a strong impression both on Margrethe and me, and on everyone at the Institute that the two of you spoke to, that you and Weizsäcker expressed your definite conviction that Germany would win and that it was therefore quite foolish for us to maintain the hope of a different outcome of the war and to be reticent as regards all German offers of cooperation. I also remember quite clearly our conversation in my room at the Institute, where in vague terms you spoke in a manner that could only give me the firm impression that, under your leadership, everything was being done in Germany to develop atomic weapons and that you said that there was no need to talk about details since you were completely familiar with them and had spent the past two years working more or less exclusively on such preparations. I listened to this without speaking since [a] great matter for mankind was at issue in which, despite our personal friendship, we had to be regarded as representatives of two

[NEW PAGE]

2

sides engaged in mortal combat. That my silence and gravity, as you write in the letter, could be taken as an expression of shock at your reports that it was possible to make an atomic bomb is a quite peculiar misunderstanding, which must be due to the great tension in your own mind. From the day three years earlier when I realized that slow neutrons could only cause fission in Uranium 235 and not 238, it was of course obvious to me that a bomb with certain effect could be produced by separating the uraniums. In June 1939 I had even given a public lecture in Birmingham about uranium fission, where I talked about the effects of such a bomb but of course added that the technical preparations would be so large that one did not know how soon they could be overcome. If anything in my behaviour could be interpreted as shock, it did not derive from such reports but rather from the news, as I had to understand it, that Germany was participating vigorously in a race to be the first with atomic weapons.

Besides, at the time I knew nothing about how far one had already come in England and America, which I learned only the following year when I was able to go to England after being informed that the German occupation force in Denmark had made preparations for my arrest.

All this is of course just a rendition of what I remember clearly from our conversations, which subsequently were naturally the subject of thorough discussions at the Institute and with other trusted friends in Denmark. It is quite another matter that, at that time and ever since, I have always had the definite impression that you and Weizsäcker

[NEW PAGE]

3

had arranged the symposium at the German Institute, in which I did not take part myself as a matter of principle, and the visit to us in order to assure yourselves that we suffered no harm and to try in every way to help us in our dangerous situation.

This letter is essentially just between the two of us, but because of the stir the book has already caused in Danish newspapers, I have thought it appropriate to relate the contents of the letter in confidence to the head of the Danish Foreign Office and to Ambassador Duckwitz.

Draft of letter from Bohr to Heisenberg, never sent.

In the handwriting of Niels Bohr's assistant, Aage Petersen.

Undated, but written after the first publication, in 1957, of the Danish translation of Robert Jungk, Heller als Tausend Sonnen, the first edition of Jungk's book to contain Heisenberg's letter

Ruth Moore. Niels Bohr: The Man, His Science, and The World They Changed. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1985 [1966]. Fission pp. 248-285, Heisenberg's wartime visit to Copenhagen, pp. 290-294.

Mines: The "deposit is claimed to be one of the largest uranium deposits in Slovakia. . . . of over 1.8 million pounds of ore, reserves amounting to 32.55 million pounds of uranium ore."

Uranium exists naturally as 92 % is U238 but can separated into rare U235 which is fissionable. That had taken an enormous amount of electricity and facilities. In the United States at Oak Ridge this required 80 square miles of metallurgical industrial engineering facilities to achieve sufficient U235 for make the Hiroshima bomb nicknamed, "Little Man."

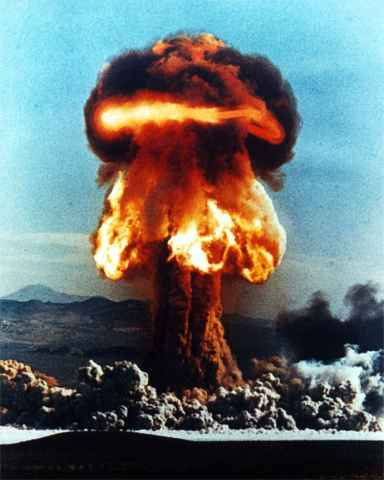

Photographic background.

The photograph in the background is the first photographic record of the atomic age, taken by a cameraman on the morning of August 3, 1945 in Hiroshima beside a railway station.