"The feeling of solitude . . . is a longing for a place."

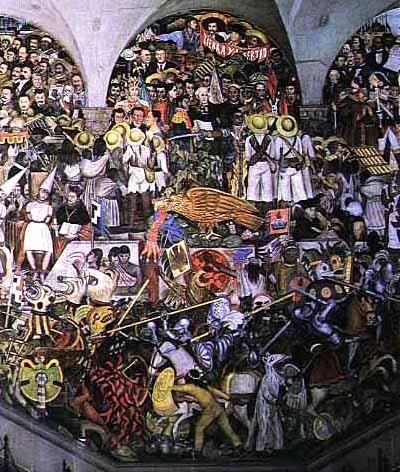

Conquest & Colonialism

“They are impalpable and invincible because they are not outside us but with in us …they are supported by a secret and powerful ally, our fear of being …Their origins are in the Conquest, the Colonial period.…”

The Labyrinth of Solitude, p. 73.

Conquest | Religion | Aztec suicide? | Spanish character | Labor | Catholicism | History | Divinity | Gender | Revolt of 1692 | The Other Mexico

"Ancient beliefs and customs are still in existence beneath western forms."

"The Chichimecas wandered among the deserts and uncultivated plains. . . . And the last centuries of Mesoamerican history can be summed up as the history of repeated encounters between waves of northern hunters -- almost all of them belonging to the Nuhuatl family -- and the settled populations. The Aztecs were the last to enter the Valley of Mexico."

"founding a Universal Empire."

p. 89.

"Mesoamerica was made up of a complex (indigenous) of autonomous peoples, nations and cultures, each with its own traditions. . . ."

p. 90.

"common to all (Mesoamerican) cultures: an agriculture based on maize, a ritual calendar, a ritual ball game, human sacrifices. solar and vegetation myths. . . ."

p. 91.

Conquest | Religion | Aztec suicide? | Spanish character | Labor | Catholicism | History | Divinity | Gender | Revolt of 1692 | The Other Mexico

"Those societies were impregnated with religion."

"This synthesis . . . . was the work of of a caste located at the apex of the social pyramid. The systematization, adaptations and reforms undertaken by the priestly caste show that the process was one of superimposition, which was also characteristic of religious architecture."

Everything was (or seemed to be) prepared for Spanish domination."

p. 92.

"The arrival of the Spanish seemed a liberation to the people under Aztec rule."

p. 93.

Their final struggle was a form of suicide, as we can gather from all the existing accounts of that grandiose and astounding event."

The gods had abandoned him. The great betrayal with which history of Mexico begins was not committed by the Tlaxcaltecas or by Moctezuma and his group: it was committed by the gods. No other people have ever felt so completely helpless as the Aztec nation felt at the appearance of the omens, prophecies and warning that announced its fall."

"Indian . . . cyclical conceptions of time."

"Time for the Aztecs" as with all indiginistas was "a substance, or fluid perpetually being used up."

p. 93.

"But time -- or more precisely, each period of time-- was not only something that was born, grew up, decayed and was reborn. It was also a succession that returned: one period of time ended and another came back."

. . . the internal conclusion of of one cosmic period and the commencement of another. The gods departed because their period of time was at an end. . . ."

pp. 93-94.

"Aztec deities express a duality whose traditions correspond to "the contradictory impulses that motivate all human beings and groups. The death-wish and the will-to-live conflict in each one of us."

pp. 95-96.

Conquest | Religion | Aztec suicide? | Spanish character | Labor | Catholicism | History | Divinity | Gender | Revolt of 1692 | The Other Mexico

Spain was still a medieval nation, and many of the institutions she brought to the new world. like many o of the men who established them, were also medieval. At the same time, the discovery and conquest of America was a Renaissance undertaking. Therefore also Spain also participated in the Renaissance, although it is sometimes thought that her overseas conquests-- the result of Renaissance science and technology and even Renaissance dreams and utopias-- did not form a part of that historical movement."

p. 97.

" . . . , But the Spanish will to create a world in its own image was also evident. In 1604, less than a century after the fall of Tenochtitlán" there is evidence of "a will to unity."

p. 99-100.

"By determining the salient features of colonial religion, whether in its popular manifestations or in those of its most representative spirits, we can discover the meaning of our culture and the origins of many of our later conflicts."

p. 100.

"Colonial society was an order built to endure."

p. 101.

"Catholicism was the center of colonial society because it was the true fountain of life, nourishing the activities, the passion, the virtues and even the sins of both lords and servants, functionaries and priests, merchants and soldiers."

Catholicism made colonial order "a living organism. . . . a universal order open to everyone," through baptism. "

p. 101.

Conquest | Religion | Aztec suicide? | Spanish character | Labor | Catholicism | History | Divinity | Gender | Revolt of 1692 | The Other Mexico

"It is clear that the reason the Spanish did not exterminate the Indians was that they needed their labor for the cultivation of the vast hacienda and the exploitation of the mines. . . . but the fate of the Indians would have been very different if it had not been for the Church."

"It is clear that the reason the Spanish did not exterminate the Indians was that they needed their labor for the cultivation of the vast hacienda and the exploitation of the mines. . . . but the fate of the Indians would have been very different if it had not been for the Church."

p. 101-102.

"To belong to the Catholic faith meant that one found a place in the cosmos."

p. 99-100.

"In the strictest sense, no society can be justified while one or another form of oppression subsists in it."

p. 103.

"But the creation of a universal order, which was the most extraordinary accomplishment of colonialism, does justify that society and redeems it from its limitations."

"a society in which all men and all races found a place, a justification, a meaning."

p. 103.

Conquest | Religion | Aztec suicide? | Spanish character | Labor | Catholicism | History | Divinity | Gender | Revolt of 1692 | The Other Mexico

"History has the cruel reality of a nightmare, and the human grandeur consists of our making beautiful and lasting works out of the real substance of that nightmare. Or, to put it another way, it consists in transforming the nightmare into vision; in freeing ourselves from the shapeless horror of reality – if only for an instant – by means of creation."

p. 104.

"This paradoxical but real situation explains a good part of our history and is the origin of many of our psychic conflicts. Catholicism offered a refuge to the descendents of those who had seen the extermination of their ruling classes, the destruction of their temples and manuscripts, and the suppression of the superior forms of their culture; but for the same reason that it was decadent in Europe, it denied them any chance of expressing their singularity. It reduced the participation of the faithful to the most elementary and passive religious attitudes."

p. 105.

The Mexican is a religious being and his experience of the divine is completely genuine.

Chamula Amerindians or First Nations are "Indiginistas".

| Spanish Catholicism | versus | Indiginistas' faith |

|---|---|---|

Mystery religion |

agrarian |

|

The trinity |

earth deities |

|

Father, Son, Spirit |

two souls : the Chulel is the soul that dwells in the animal and the other dwells in the body. |

|

Order from rational hierarchy |

cosmic order from Sun deities |

|

condemns the world to save the single individual soul |

personal salvation only as part of the salvation of society and the cosmos. |

"In many instances Catholicism only covers over the ancient cosmogonic beliefs."

"Under these conditions, the persistence of the pre-Cortesian background is not surprising. The Mexican is a religious being and his experience of the divine is completely genuine. But who is his god? . . . . In many instances Catholicism only covers over the ancient cosmogonic beliefs."

pp. 106-107."

"Therefore the Chamula says that thanks to the presence of God, nature becomes active."

p. 107.

Conquest | Religion | Aztec suicide? | Spanish character | Labor | Catholicism | History | Divinity | Gender | Revolt of 1692 | The Other Mexico

She "penetrates reality" as opposed to others describing the world she did not "transmute it into a delightful surface."

"In her Paz discovered "a clash of opposing tendencies that she could not reconcile."

p. 112- 113.

Sor Juana lived in "A world that denied the value of doubt and inquiry."

p. 114.

"It was a world open to participation, was even a living cultural order, but it was implacably closed to all personal expression and all adventure: it was a world closed to the future."

Suppressed after the riot of 1692 and Pueblo revolt of 1696 in New Mexico.

"To be ourselves we had to break with this exitless order."

p. 116.

Conquest | Religion | Aztec suicide? | Spanish character | Labor | Catholicism | History | Divinity | Gender | Revolt of 1692 | The Other Mexico

![]()

THE OTHER MEXICO (Oct. 30, 1969)