.gif) The Great South Sea Bubble

The Great South Sea Bubble

"Natural beauty is from geometry."

Christopher Wren

The mania started in 1711, after Queen Anne's War which left Britain in debt by 10 million pounds.  Britain proposed a deal to a financial institution, the South Sea Company, where Britain’s debt would be financed in return for 6% interest. Britain added another benefit to sweeten the deal: exclusive trading rights in the south seas. South seas meant Africa, East and West Indies, South America and Asia.

Britain proposed a deal to a financial institution, the South Sea Company, where Britain’s debt would be financed in return for 6% interest. Britain added another benefit to sweeten the deal: exclusive trading rights in the south seas. South seas meant Africa, East and West Indies, South America and Asia.

The British government of 1711 had spent itself into debt totaling over ten million pounds. In a startling and still confusing move, a large group of merchants joined together and bought some £9,000,000 of the debt, assured by the government of a six percent interest rate.

Hogarth's, "Exchange Alley," 1721

Perhaps you've heard of these merchants before: the famous South Sea Trading Company.

If you think about it, that's not a bad deal: £540,000 income guaranteed annually.

The South Sea Company quickly agreed, because of the proximity to wealthy South American colonies. The company planned on developing a monopoly in the slave trade. Additionally it was thought that the Mexicans and South Americans would eagerly trade their gold and jewels for the wool and fleece clothing of the British.

The South Sea Company issued stock to finance operations and gain investors. Investors quickly saw what they perceived as value in the monopoly of the South Seas. Shares were quickly snatched up from the start. The South Sea Company, seeing the success of the first issue of shares, quickly issued even more. This stock was rapidly consumed by the voracious appetite of the investors. Investors had no quibble, despite having a highly inexperienced management team. All they saw was that the stock was going to the stratosphere.

South Seas (Atlantic and Pacific Oceans) and China Seas

While the directors of the Company insisted profits were just around the corner, and even outbid the Bank of England for an additional £31,000,000 of government debt in 1719, one dreary day in September 1720 no one wanted to buy stocks.

With no buyers, the poor bastards who had bought stock for thousands of pounds could hope to unload it for only a fraction of the price they had  paid. The few that figured this out before it happened made out like bandits (One Alexander Pope comes to mind). An entire generation lay in pieces. A pamphlet published in Boston in 1721 notes:

paid. The few that figured this out before it happened made out like bandits (One Alexander Pope comes to mind). An entire generation lay in pieces. A pamphlet published in Boston in 1721 notes:

...many poor Families have been ruined,

brought to Poverty,

and turned beggars.

The Trade of the City of London, one of the finest in the World,

hath been very much shortned,

few Ships have been built,

or fitted to Sea,

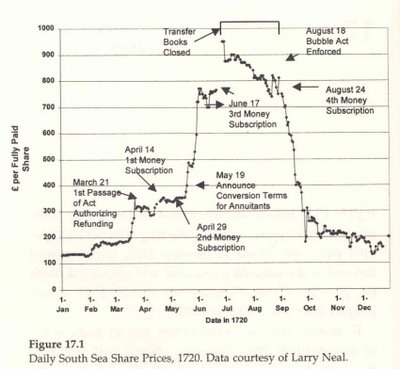

during the Reign of the South-Sea Company.Wikipedia has an excellent entry on it, from which the above chart of the South Seas Company stock price is taken.

The rest of the country languished in misery and poverty. The investors were equally split between two strategies: (1) buying stock with no real value (i.e., walnuts from Virginia) hoping to sell it at a higher price to stupid persons, and, of course, (2) plain stupidity.

The directors of the South-Sea Company, the suddenly-wealthy authors of this bubble, got together with disgruntled investors and told them what great deeds the Company had done for England. MacKay tells us they claimed, "none had ever performed such wonderful things in so short a time as the South-Sea Company... monied men had vastly increased their fortunes; country gentlemen had seen the value of their lands doubled ...in short, [they] had enriched the whole nation." And then they ran, much to the consternation of everybody else who had suddenly found themselves in the poorhouse.

One such sucker, Lord Molesworth [remember, this whole event took place with the endorsement of the British Parliament, of which he was a member], decided that while no law existed to punish this company, they ought to make one in a hurry: "In his opinion," MacKay recounts, "they ought upon this occasion follow the example of the ancient Romans, who, having no law against parricide, because their legislators supposed no son could be so unnaturally wicked as to embrue his hands in his father's blood, made a law to punish this heinous crime as soon as it was committed. They adjudged the guilty wretch to be sewn into a sack and thrown alive into the Tiber... he should be satisfied to see [the South-Sea Company directors] tied in like manner in sacks, and thrown into the Thames." A few directors and Parliament members were subjects of fairly uneventful inquiries, save for Earl Stanhope. He managed to whip himself into a frenzy after brunting some accusations, and passed out in the House of Commons. He "let blood the on the following morning, but with slight relief." It was eighteenth-century England, and everyone knew that a good healthy bleeding would make you fresh as a daisy. However, MacKay follows that sentence with, "The fatal result was not anticipated."

Source. [ History House: "We here at HH would like to note that while its success rate is low, stupidity is probably the most-often used strategy in humanity's playbook."]

The South Seas Bubble (1720) is one of history's most notorious market bubbles. Very smart people lost fortunes in the scheme such as Sir Isaac Newton who lost the equivalent of today's $4 million. The Company actually made little profit from trading goods and slaves with the Spanish colonies in South America - as was the charter of the Company. The bubble was formed, instead, when the company arranged to take over a large portion of England's public debt.

In 1720, when South Sea's stock soared in the wake of speculation and greed surrounding the monopoly the South Sea Company was perceived to have in the shipping and trade industries, particularly in Mexico and parts of South America.

With nothing to prevent it from doing otherwise, South Sea Company's management continued to issue shares in response to seemingly insatiable demand. As a result, the stock's price soared, defying all fundamental sense. Eventually, the truth was exposed: the company was making virtually no profit, and the share price plummeted when investors fled.

So "largely through the pressure of the South Sea directors, the so-called "Bubble Act" was passed on June 11, 1720 requiring all joint-stock companies to have a royal charter. For a moment the confidence of the people was given an extra boost, and they responded accordingly. South Sea stock had been at 175 pounds at the end of February, 380 at the end of March, and around 520 by May 29. It peaks at the end of June at over 1000 pounds.

With credulity now stretched to the limit and rumors of more and more people (including the directors themselves) selling off, the bubble then bursts. To be accurate, it suffers a puncture and begins a slow, very slow at first, but steady deflation. By mid August the bankruptcy listings in the London Gazette reach an all-time high, an indication of how people bought on credit or margin. Thousands of fortunes are lost, both large and small. The directors attempt to pump-up more speculation. They fail. The full collapse comes by the end of September when the stock stands at 135 pounds.

The last part of the story may be told in that investors scream foul against the South Sea directors. Parliament is recalled and George I hastens back to London. Mobs crowd into Westminster. A committee is form to investigate the South Sea Company; by early 1721 it uncovers widespread corruption and fraud among the directors, company officials and their friends at Westminister. Unfortunately, some of the key players have already fled the country with the incriminating records in their possession. Those who remain are examined and some estates are confiscated. Robert Walpole then rises to power with some reasonable proposals to restore public confidence. They take effect but the "Bubble" affected the fortunes of several families and remained in the consciousness of the Western world for the rest of the eighteenth century."

The South Sea Bubble: A Short Sketch of Events

An interdisciplinary scholarly effort: The Bubble Project.