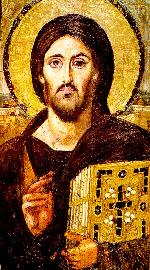

Two of the four icons presented here are among the oldest extant Byzantine icons, painted in encaustic, an early technique involving beeswax. They were discovered at the Monastery of St. Catherine at Mt. Sinai and date back to the 6th century. They are important not only as a proof that icon painting before the period of iconoclasm achieved a high level of excellence, but as a basis of hypotheses about the developments in iconography.

The Savior (6th c.)

The bust of the Savior is life sized, a common feature

of early icons, and shows a traditional monumental image of Christ holding

a Gospel book in his left hand while blessing with his right. The icon

has been amazingly well preserved in the dry air of the Sinai Peninsula.

The Savior presented on the Sinai icon has a magnetically attractive face.

It is slightly asymmetrical, perhaps indicating the dual nature of Christ

or his protective and judgmental sides. One can sense an affinity between the eyes of this Byzantine image

and those that would be produced in Russia in the coming centuries, especially

Andrei Rublev's. Christ is dressed in

the traditional purple tunic. The halo surrounding his head appears to

have had, at one time, a cross and a row of decorative beads around its

circumference. An interesting aspect of this painting is the difference

in the color of the face of Christ and the color of his hands. According

to Kurt Weitzmann, "[the] high quality

of this icon rests both on the subtle, refined, and lively rendering of

the flesh areas, which still display a full command of the classical tradition,

and on the artist's ability to transcend Christ's human nature by conveying

the impression of aloofness and timelessness associated with the Divine.

Yet rigidity is avoided by a striking asymmetry, evident in the pupils

of the wide open eyes, the arching of the brows, the treatment of the mustache,

and the combing of the beard, as well as the flow of the hair" (1978, 40).

The bust of the Savior is life sized, a common feature

of early icons, and shows a traditional monumental image of Christ holding

a Gospel book in his left hand while blessing with his right. The icon

has been amazingly well preserved in the dry air of the Sinai Peninsula.

The Savior presented on the Sinai icon has a magnetically attractive face.

It is slightly asymmetrical, perhaps indicating the dual nature of Christ

or his protective and judgmental sides. One can sense an affinity between the eyes of this Byzantine image

and those that would be produced in Russia in the coming centuries, especially

Andrei Rublev's. Christ is dressed in

the traditional purple tunic. The halo surrounding his head appears to

have had, at one time, a cross and a row of decorative beads around its

circumference. An interesting aspect of this painting is the difference

in the color of the face of Christ and the color of his hands. According

to Kurt Weitzmann, "[the] high quality

of this icon rests both on the subtle, refined, and lively rendering of

the flesh areas, which still display a full command of the classical tradition,

and on the artist's ability to transcend Christ's human nature by conveying

the impression of aloofness and timelessness associated with the Divine.

Yet rigidity is avoided by a striking asymmetry, evident in the pupils

of the wide open eyes, the arching of the brows, the treatment of the mustache,

and the combing of the beard, as well as the flow of the hair" (1978, 40).

John the Baptist (6th c.)

The second early icon, of John the Baptist, is not

as well preserved. At the top of the panel we may still see the two small

medallions, of Christ on the left, and of the Virgin on the right, forming,

together with the head of St. John, a simple, albeit reshuffled, Deesis,

expressing the idea of the intercession. St. John is dressed in a brown

tunic and mantle, and in a sheepskin (melote), often emphasized in later

icons. Weitzmann believes that "the

highlights in the face underlining John's visionary power and the fleeting

brush strokes on his garments still reflect strongly the classical tradition.

We see here one of the oldest icons in existence: whether it could belong

to the fifth century is an open question, and more safely we may ascribe

it to the sixth. We do not know where the icon might have been painted.

Since it is so different in style from the three great masterpieces. .

. that we attribute to Constantinopolitan workshops, we hesitate to propose

an origin in the Capital for this icon and consider Palestine a possible

place of origin" (1978, 52).

The second early icon, of John the Baptist, is not

as well preserved. At the top of the panel we may still see the two small

medallions, of Christ on the left, and of the Virgin on the right, forming,

together with the head of St. John, a simple, albeit reshuffled, Deesis,

expressing the idea of the intercession. St. John is dressed in a brown

tunic and mantle, and in a sheepskin (melote), often emphasized in later

icons. Weitzmann believes that "the

highlights in the face underlining John's visionary power and the fleeting

brush strokes on his garments still reflect strongly the classical tradition.

We see here one of the oldest icons in existence: whether it could belong

to the fifth century is an open question, and more safely we may ascribe

it to the sixth. We do not know where the icon might have been painted.

Since it is so different in style from the three great masterpieces. .

. that we attribute to Constantinopolitan workshops, we hesitate to propose

an origin in the Capital for this icon and consider Palestine a possible

place of origin" (1978, 52).

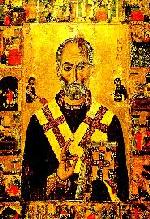

St. Nicholas the Miracleworker

(12th-13th c.)

The third icon among our examples, St. Nicholas

the Miracleworker, with Scenes from His Life, also comes from Sinai,

but it is a later work, from the end of the twelfth or the first half of

the thirteenth century. The saint is an amalgamation of two St. Nicholases,

a bishop of the fourth century and a pious monk of the sixth. By the twelfth

century St. Nicholas has become one of the most beloved and popular saints,

not only in the Byzantine Empire but in Russia and the West. He was considered

the patron of sailors, seamen, and fishermen, scholars, students and teachers,

merchants, traders, marriageable maidens, bankers, and even robbers and

thieves. Hagiographical icons of the saint presented in the middle his

bust (in Russia, also his standing figure) and a selection of episodes

from his life and from his posthumous miracles framing the central image.

The icon shown here includes 16 episodes, from the saint's birth to his death.

The monumental character of the central panel is softened by an addition

of interesting decorative details. The hair and the beard of the saint

are fancifully outlined by flowing white curls and the crosses on the saint's

omophorion show intricate design. Next to Nicholas' head are two small

figures: on the left Christ with a Gospel book, and on the right the Virgin

with an omophorion. These two figures allude to the story of the saint's

presence at the First Ecumenical Synod in Nicaea in 325. According to the

story, Nicholas, angered by the blasphemous words of the heretic Arius

against the Holy Trinity, slapped him on the face. For this, he was put

in prison and his bishop's attributes, the Gospel Book and the omophorion,

were taken from him. However, at night, Christ and the Virgin appeared

in his prison cell and returned the Gospel book and the omophorion to him,

forcing Emperor Constantine to free the saint and reinstate him as a bishop.

In Russia, St. Nicholas became the most popular saint of all, depicted

in literally thousands of icons, ranging from simple busts to very elaborate

hagiographical icons with more than forty border scenes.

The third icon among our examples, St. Nicholas

the Miracleworker, with Scenes from His Life, also comes from Sinai,

but it is a later work, from the end of the twelfth or the first half of

the thirteenth century. The saint is an amalgamation of two St. Nicholases,

a bishop of the fourth century and a pious monk of the sixth. By the twelfth

century St. Nicholas has become one of the most beloved and popular saints,

not only in the Byzantine Empire but in Russia and the West. He was considered

the patron of sailors, seamen, and fishermen, scholars, students and teachers,

merchants, traders, marriageable maidens, bankers, and even robbers and

thieves. Hagiographical icons of the saint presented in the middle his

bust (in Russia, also his standing figure) and a selection of episodes

from his life and from his posthumous miracles framing the central image.

The icon shown here includes 16 episodes, from the saint's birth to his death.

The monumental character of the central panel is softened by an addition

of interesting decorative details. The hair and the beard of the saint

are fancifully outlined by flowing white curls and the crosses on the saint's

omophorion show intricate design. Next to Nicholas' head are two small

figures: on the left Christ with a Gospel book, and on the right the Virgin

with an omophorion. These two figures allude to the story of the saint's

presence at the First Ecumenical Synod in Nicaea in 325. According to the

story, Nicholas, angered by the blasphemous words of the heretic Arius

against the Holy Trinity, slapped him on the face. For this, he was put

in prison and his bishop's attributes, the Gospel Book and the omophorion,

were taken from him. However, at night, Christ and the Virgin appeared

in his prison cell and returned the Gospel book and the omophorion to him,

forcing Emperor Constantine to free the saint and reinstate him as a bishop.

In Russia, St. Nicholas became the most popular saint of all, depicted

in literally thousands of icons, ranging from simple busts to very elaborate

hagiographical icons with more than forty border scenes.

The Virgin Eleousa of Vladimir (12th c.)

The fourth icon, the so-called Virgin of Vladimir,

possibly the most famous icon of Russia, is not a Russian icon, but a gift

brought from Constantinople to Russia in 1131. Prince Andrei

Bogoliubskii moved the icon from Kiev to the city of Vladimir in 1155.

In 1395 the icon was permanently transferred to Moscow; amazingly, the

transfer took place on the same day as the withdrawal of Khan Tokhtamysh's

forces besieging Moscow. From the very beginning the icon was considered

a work of such an outstanding quality and power that it was constantly

copied, producing numerous variations on the theme. The composition is

known as the Virgin Eleousa (of Tenderness, Umilenie): "The Virgin holds

the Child in her right arm and points at him with her left hand, while

the Child puts his left arm around the Virgin's neck and presses his cheek

against hers... Although the gestures indicate a close relationship,

the Virgin's face does not so much express maternal affection as it does--if

any term of human emotion can be applied--slight melancholy, as if she

were foreseeing the Passion of her son, prefiguring in this respect a later,

related icon type in which the implements of Christ's Passion were added.

The almond-shaped eyes, the narrow, elegantly drawn nose, the dark olive

green shadows in the face--all these features have a dematerializing effect,

stressing the Divine" (Weitzmann 1978,

80). [S.H. and A.B.]

The fourth icon, the so-called Virgin of Vladimir,

possibly the most famous icon of Russia, is not a Russian icon, but a gift

brought from Constantinople to Russia in 1131. Prince Andrei

Bogoliubskii moved the icon from Kiev to the city of Vladimir in 1155.

In 1395 the icon was permanently transferred to Moscow; amazingly, the

transfer took place on the same day as the withdrawal of Khan Tokhtamysh's

forces besieging Moscow. From the very beginning the icon was considered

a work of such an outstanding quality and power that it was constantly

copied, producing numerous variations on the theme. The composition is

known as the Virgin Eleousa (of Tenderness, Umilenie): "The Virgin holds

the Child in her right arm and points at him with her left hand, while

the Child puts his left arm around the Virgin's neck and presses his cheek

against hers... Although the gestures indicate a close relationship,

the Virgin's face does not so much express maternal affection as it does--if

any term of human emotion can be applied--slight melancholy, as if she

were foreseeing the Passion of her son, prefiguring in this respect a later,

related icon type in which the implements of Christ's Passion were added.

The almond-shaped eyes, the narrow, elegantly drawn nose, the dark olive

green shadows in the face--all these features have a dematerializing effect,

stressing the Divine" (Weitzmann 1978,

80). [S.H. and A.B.]