In the West, Neo-primitivism was an aftermath of the exhibition of the folk arts of Africa, Australia, and Oceania in Paris. The world of art was surprised by the boldness of colors, originality of designs, and the expressiveness of these "unschooled," spontaneous creations of the "primitives." In Russia, flourishing between 1907-1912 and officially launched at the 3rd

Golden Fleece Exhibition in 1909, Neo-primitivism was championed by

Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, although many other artists went through a Neo-primitivist stage. The genesis of the style can be found in the folk art of Russia -- such as the lubok (popular print) and peasant applied art (distaffs, spoons, embroideries), but even more in icon painting. Goncharova, Larionov, Malevich, Tatlin, even

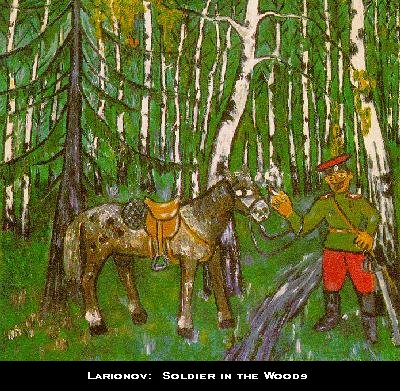

Chagall and Kandinskii incorporated into their works ideas and compositions common in icon painting. Neo-primitivist canvasses share with icons a pronounced one-dimensionality (flatness), lack of depth and perspective, distortions of "reality," as well as a bold, striking colors. Although the forms are intentionally distorted and resemble children's pictures, the paintings' rhythm and harmony come from "the music of color and line" (Gray, 75). Larionov's Soldier in the Woods (1908-9), an early example from the Soldiers series, deliberately violates the laws of perspective by making the surface of the canvas flat and decorative. The proportions of the composition are distorted -- the horse is small and the head and hands of the soldier are unusually large. Moreover, Larionov employs a limited number of primary colors, applied without shading and blending. All these artistic devices find parallels in the art of the Russian folk, particularly in icons, street signs, wooden toys, decorated distaffs, and lubok (usually hand colored in red, green, purple, and yellow). [C.B. and B.B.]

In the West, Neo-primitivism was an aftermath of the exhibition of the folk arts of Africa, Australia, and Oceania in Paris. The world of art was surprised by the boldness of colors, originality of designs, and the expressiveness of these "unschooled," spontaneous creations of the "primitives." In Russia, flourishing between 1907-1912 and officially launched at the 3rd

Golden Fleece Exhibition in 1909, Neo-primitivism was championed by

Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, although many other artists went through a Neo-primitivist stage. The genesis of the style can be found in the folk art of Russia -- such as the lubok (popular print) and peasant applied art (distaffs, spoons, embroideries), but even more in icon painting. Goncharova, Larionov, Malevich, Tatlin, even

Chagall and Kandinskii incorporated into their works ideas and compositions common in icon painting. Neo-primitivist canvasses share with icons a pronounced one-dimensionality (flatness), lack of depth and perspective, distortions of "reality," as well as a bold, striking colors. Although the forms are intentionally distorted and resemble children's pictures, the paintings' rhythm and harmony come from "the music of color and line" (Gray, 75). Larionov's Soldier in the Woods (1908-9), an early example from the Soldiers series, deliberately violates the laws of perspective by making the surface of the canvas flat and decorative. The proportions of the composition are distorted -- the horse is small and the head and hands of the soldier are unusually large. Moreover, Larionov employs a limited number of primary colors, applied without shading and blending. All these artistic devices find parallels in the art of the Russian folk, particularly in icons, street signs, wooden toys, decorated distaffs, and lubok (usually hand colored in red, green, purple, and yellow). [C.B. and B.B.]