Commission for Racial Justice, 1987.

“we call attention to the fact that race is a major factor relating to the presence of hazardous wastes in residential communities throughout the United States.”

Carolyn Merchant, p. 504.

“people who live in potentially health-threatening situations.”

“take this issue seriously.”

“take this issue seriously.”

“No residential community, regardless of race, should ever be left defenseless in the midst of this mounting crisis.”

“Since 1982, we have investigated and challenged the alarming presence of toxic substances in residential areas across the country.”

“ the relationship between treatment, storage and disposal of hazardous wastes and the issue of race.”

“Racism is more than just a personal attitude; it is the institutionalized form of that attitude.”

“racial prejudice plus power,”

“enforced and maintained by the legal, cultural, religious, educational, economic, political, and military institutions of societies.”

Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr. , Executive Director

United Church of Christ.

-a 1.7 million member religious body

“Unfortunately, racial and ethnic Americans are far more likely to be unknowing victims of exposure to such substances.”

p. 505.

GAO reported that the EPA had no idea if it had identified 90 percent or 10 percent of the potentially hazardous waste sites.

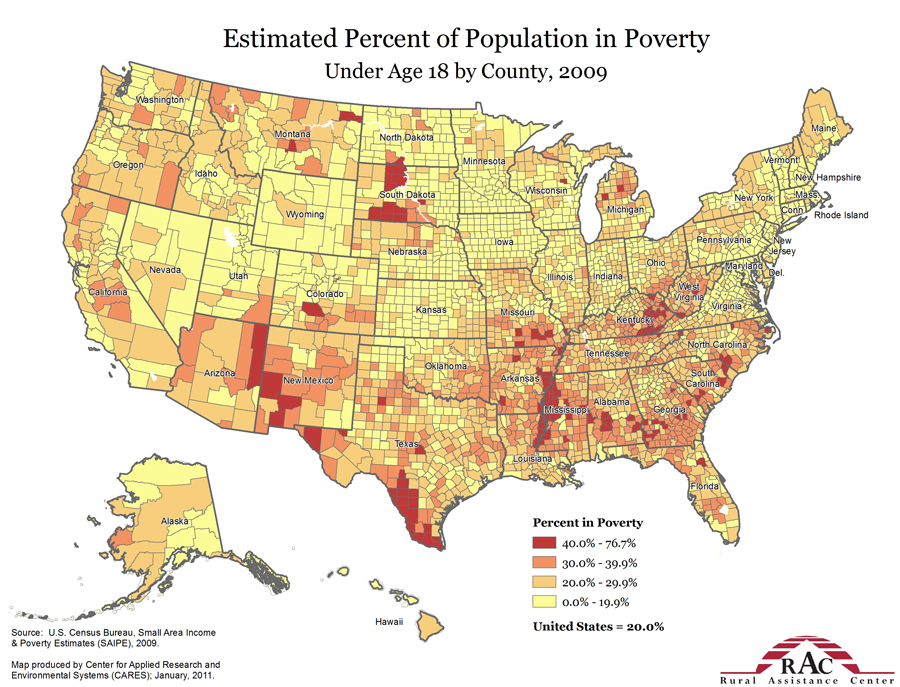

In three out of four southeastern communities the GAO study found that the population was African American minority members.

“A consistent national pattern.”

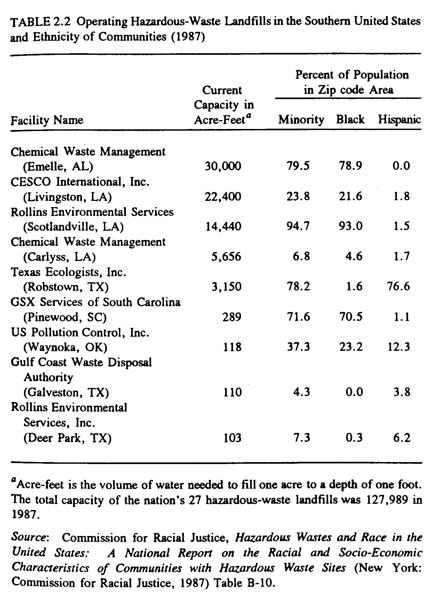

“Communities with two or more facilities or one of the nations five largest landfills, the average minority percentage of the population was more than three times that of communities without facilities (38 percent vs. 12 percent).

p. 506.

Socio economic status was important but was outweighed by race

p. 506.

“Three out of five largest commercial hazardous waste landfills in the United States were located in predominantly Black or Hispanic communities. These three landfills accounted for 40 percent of the total estimated commercial landfill capacity of the nation…”

“make this a priority concern.”

p. 506.

Statistics from:

Bullard, R. D. Dumping in Dixie: Race, class, and environmental quality. Boulder, CO: Westview. 1990.

CHAPTER TWO: Race, Class, and the Politics of Place

The southern United States, with its unique history and its plantation-economy legacy, presents an excellent opportunity for exploring the environment-development dialectic, residence-production conflict, and residual impact of the de facto industrial policy (i.e., "any job is better than no job") on the region's ecology. The South during the 1950s and 1960s was the center of social upheavals and the civil rights movement. The 1970s and early 1980s catapulted the region into the national limelight again, but for different reasons. The South in this latter period was undergoing a number of dramatic demographic. economic, and ecological changes. It had become a major growth center.

Growth in the region during the 1970s was stimulated by a number of factors. They included (12) a climate pleasant enough to attract workers from other regions and the "underemployed" workforce already in the region, (2) weak labor unions and strong right-to-work laws, (3) cheap labor and cheap land, (4) attractive areas for new industries, i.e., electronics, federal defense, and aerospace contracting, (5) aggressive self-promotion and booster campaigns. and (6) lenient environmental regulations [1] Beginning in the mid-1970s, the South was transformed from a "net exporter of people to a powerful human magnet."[2] The region had a number of factors it promoted as important for a "good business climate," including "low business taxes, a good infrastructure of municipal services, vigorous law enforcement, an eager and docile labor force, and a minimum of business regulations."[3]

The rise of the South intensified land-use conflicts revolving around "use value" (neighborhood interests) and "exchange value" (business interests).

http://www.ciesin.org/docs/010-278/tab2-2.gif

4/6/09 10:48 PM