Stephen Jay Gould

"a statement about history and the awesome improbability of human evolution."

As the late Stephen Gould has written: ". . . I state that the invertebrates of the Burgess Shale, found high in the Canadian Rockies. . . , are the world's most important animal fossils."

Wonderful Life, (1989), p. 23.

He pointed out that "Modern multicellular animals make their first uncontested appearance in the fossil record dome 570 million years ago – . . . This 'Cambrian explosion' marks the advent of virtually all major groups of modern animals – and within the miniscule span, geologically speaking, of a few million years."

"The Burgess shale is our only extensive, well-documented window on that most crucial event in the history of animal life, the first flowering of the Cambrian explosion."

The period is named after the rocks first unearthed and dated in Cambria the Latin name for Wales, during the canal & railway building eras in the United Kingdom, during the 18th and 19th centuries.

"the riddles of existence"

"The history of life is a story of massive removal followed by differentiation within a few surviving stocks, not the conventional take of steadily increasing excellence, complexity, and diversity."

p. 25.

"Harry Whittington and his colleagues have shown that most Burgess organisms do not belong to familiar groups, and that the creatures from this single quarry in British Columbia probably exceed, in anatomical range, the entire spectrum of invertebrate life in today's oceans."

pp. 24-25.

"The Burgess Shale includes a range of disparity in anatomical design never again equaled, and not matched today by all the creatures the in all the world's oceans. The history of multicellular life has been dominated by decimation of a large initial stock, quickly generated in the Cambrian explosion. . . . restriction followed by by proliferation within a few stereotyped designs, not general expansion of range and increase in complexity as our favored iconography, the cone of increasing diversity, implies."

p. 208.

Anomalocaris, predator of the Cambrian seas.

". . . the entire animal must have dwarfed nearly everything else in the Burgess Shale. Whittington and Briggs estimated the biggest specimen as nearly two-feet in length, by far the largest of all Cambrian animals."

". . . the entire animal must have dwarfed nearly everything else in the Burgess Shale. Whittington and Briggs estimated the biggest specimen as nearly two-feet in length, by far the largest of all Cambrian animals."

p. 202.

"Since Anomalocaris has no body appendages , it presumably did not walk or crawl along the substrate. . . . a capable swimmer, though no speed demon, propelled by wavelike motions of the body lobes in coordinated sequences."

p. 205.

The Nearshore nurseries of ocean fisheries.

The Nearshore nurseries of ocean fisheries.

Extinction is the future of all species. But the cost of any loss in often underestimated, because species depend on one another. Take for example the loss of the limpet Lottia alveus. The species extinction seems not to matter much in the big scheme of things, unless you look more carefully. He refers to the eelgrass (Zostera) limpet of the Eastern Atlantic, "this limpet lacked the flexibility of all other species associated with Zostera." Gould noted the last living specimens of the Atlantic variety were reported in 1933. This was because once the Zostera virtually disappeared from marine waters where the limpet thrived; the estuarine refuge for the eelgrass did not prove to be a sufficient refuge for limpet populations.

The marine grass and the snail are but a parable of the problem of looking at data in isolation. The larger context for creating a list or carefully identifying the signals that nature is sending us about the health of an animal’s range or the morbidity and age grouping of a population is that species are being lost.

Beautiful or ugly, species are being extinguished in their ranges, or becoming extinct in the world at pace that exceeds all past natural extinctions except the most catastrophic in the Permian and the Cretaceous periods. Our criteria for preserving these creatures can’t rest on their size, or their attractiveness, but must always consider their functional role in shaping and be shaped by the very places where they have dwelt for thousands of years. They are the traffic signal on nature’s “information highway, alerting us about ambient conditions, on which our journey’s safety depends.

Gould concluded about the limpet, that in the oceans that were once believed to be an invulnerable place of refuge, this tiny snail perished when conditions, competition and its prey's range was adversely affected by events. Gould's message is worth recalling, "How appropriate," he wrote, "then, as a warning against complacency, that a real version of this symbol (the Lottia living amidst the eel grasses of an enormously wide oceans) should be the first species to die in a realm of supposed invulnerability." The removal of a small bird from the endangered list -- a woodpecker that is nourished in old trees, whose life cycles depend on fire for their rejuvenation and seed setting, may not seem like a huge matter. But having lost the Dusky Seaside Sparrow, we are as vulnerable to our mistakes in science and policy as we are to the decisions of wildlife Commissioners who fail to see the context we are now experiencing. Gould said the Lottia’s extinction is a warning against complacency that we should all take away from this loss.

The 2006 decision of Florida to change the status of the Red-Cockaded woodpecker bird on paper, when Ornithologists insist and the rest of us have a good hunch that the natural conditions remain as perilous as ever, is an even more urgent wake-up call. The warning is all the more important because recovery does not mean simply that more creatures are here today than there were yesterday. Recovery means the species must face and adapt to new threats.

So when E. O. Wilson says that the stability and productivity of a natural area is enhanced by biological diversity, we must be willing to consider the impact of the parts, together, on the integrity of the whole living system. Wilson has argued for functional reasons of an environment we need to protect species. Economically the value to the world of endangered habitats and species is in the billions of dollars due to their scientific or medicinal importance. But in a wider sense the value of a species that we preserve is in what it says about our capacity to learn from our mistakes.

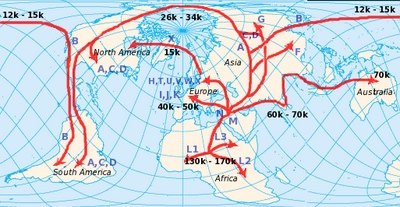

Human migratory patterns from DNA evidence.

Stephen Jay Gould. Wonderful Life, The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. (New York: W.W. Norton, 1989), pp. 23-205.

Stephen Jay Gould. Wonderful Life, The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. (New York: W.W. Norton, 1989), pp. 23-205.

Karen Carr's artistic recreation of the Burgess shale ecosystem.

Gavan P. L. Watson notes that "Researches at the University of Alberta have found that significantly more frogs & toads ( 5.7 more new wood  frogs [Rana sylvatica], 29 times more western toads [Bufo boreas] and 24 times more boreal chorus frogs [Pseudacris maculata] ) could be found in the ponds created behind beaver (Castor canadensis) dams when compared to nearby free-flowing bodies of water. Reasons for the amphibian’s success are suggested as the warmer, well-oxygenated water that is created in the new beaver pond habitat.

frogs [Rana sylvatica], 29 times more western toads [Bufo boreas] and 24 times more boreal chorus frogs [Pseudacris maculata] ) could be found in the ponds created behind beaver (Castor canadensis) dams when compared to nearby free-flowing bodies of water. Reasons for the amphibian’s success are suggested as the warmer, well-oxygenated water that is created in the new beaver pond habitat.

Dr. Cindy Paszkowski, one of the researchers suggests that:

“The concept of surrogate species in conservation planning offers simple, ecologically-based solutions to help conserve and manage ecosystems”

Posted on January 11, 2007, by Gavan P.L. Watson: A website proudly muddying the line between my private and public persona.

Leave a Comment