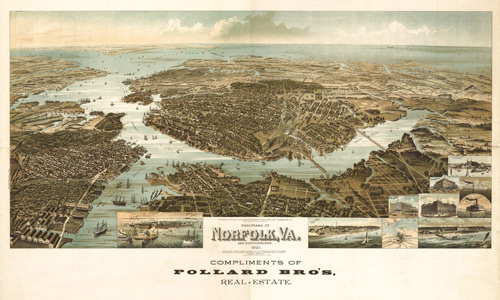

![]() The situation of Norfolk & life along the James River, 1853

The situation of Norfolk & life along the James River, 1853

A

JOURNEY

IN THE

SEABOARD SLAVE STATES;

WITH REMARKS ON THEIR ECONOMY.

Page 135

THE JAMES RIVER.

The shores of the James river are low and level--the scenery uninteresting; but frequent planters' mansions, often of great size and of some elegance, stand upon the bank, and sometimes these have very pretty and well-kept grounds about them--finer than any other I have seen at the South--and the plantations surrounding them are cultivated with neatness and skill. Many men distinguished in law and politics here have their homes.

I was pleased to see the appearance of enthusiasm with which some passengers, who were landed from our boat at one of these places, were received by two or three well-dressed negro servants, who had come from the house to the wharf to meet them. Black and white met with kisses, and the effort of a long-haired sophomore to maintain his supercilious dignity, was quite ineffectual to kill the kindness of a fat mulatto woman, who joyfully and pathetically shouted, as she caught him off the gang-plank, "Oh Massa George, is you come back!" Field negroes, standing by, looked on with their usual besotted expression, and neither offered nor received greetings.

NORFOLK.

I arrived in Norfolk on the eve of a terrific gale, during which vessels at anchor in the Roads went down, and the city and country were much excited by various disasters, both on shore and at sea.

Norfolk (slightly later 1890s).

JAN. 10th. Norfolk is a dirty, low, ill-arranged town, nearly divided by a morass. It has a single creditable public building, a number of fine private residences, and the polite society is reputed to be agreeable, refined, and cultivated, receiving a character from the families of the resident naval officers. It has

Page 136

all the immoral and disagreeable characteristics of a large seaport, with very few of the advantages that we should expect to find as relief to them. No lyceum or public libraries, no public gardens, no galleries of art, and though there are two "BETHELS," no "home" for its seamen; no public resorts of healthful and refining amusement, no place better than a filthy, tobacco-impregnated bar-room or a licentious dance-cellar, so far as I have been able to learn, for the stranger of high or low degree to pass the hours unoccupied by business.

Lieut. Maury has lately very well shown what advantages were originally possessed for profitable commerce at this point, in a report, the intention of which is to advocate the establishment of a line of steamers hence to Para, the port of the mouth of the Amazon. I have the best wishes for the success of the project in its important features, and the highest respect for the judgment of Lieut. Maury, but it seems to me pertinent to inquire why are the British Government steamers not sent exclusively to Halifax, the nearest port to England, instead of to the more distant and foreign port of New York? If a Government line of steamers should be established between Para and Norfolk, and should be found in the least degree commercially profitable, how long would it be before another line would be established between New York and Para, by private enterprise, and then how much business would be left for the Government steamers while they continued to end their voyage at Norfolk? So, too, with regard to a line from Antwerp to Norfolk, (a proposition to grant State aid for establishing which, was the chief topic of public discussion in Virginia, at the time of my visit). Lieut. Maury says, however:

"Norfolk is in a position to have commanded the business of the

Page 137

Atlantic sea-board: it is midway the coast. It has a back country of great facility and resources; and, as to approaches to the ocean, there is no harbor from the St. Johns to the Rio Grande that has the same facilities of ingress and egress at all times and in all weathers. * * The back country of Norfolk is all that which is drained by the Chesapeake Bay--embracing a line drawn along the ridge between the Delaware and the Chesapeake, thence northerly, including all of Pennsylvania that is in the valley of the Susquehanna, all of Maryland this side of the mountains, the valleys of the Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James rivers, with the Valley of the Roanoke, and a great part of the State of North Carolina, whose only outlet to the sea is by the way of Norfolk."

THE NEGLECTED OPPORTUNITIES OF NORFOLK.

This is a favorite theme with Lieut. Maury, who is a Virginian. In a letter to the National Intelligencer, Oct. 31, 1854, after describing similar advantages which the town possesses to those enumerated above, he continues:

"Its climate is delightful. It is of exactly that happy temperature where the frosts of the North bite not, and the pestilence of the South walks not. Its harbor is commodious and safe as safe can be. It is never blocked up by ice. It has the double advantage of an inner and an outer harbor. The inner harbor is as smooth as any mill-pond. In it vessels lie with perfect security, where every imaginable facility is offered for loading and unloading."

* * * *

"The back country, which without portage is naturallytributary to Norfolk, not only surpasses that which is tributary to New York in mildness of climate, in fertility of soil, and variety of production, but in geographical extent by many square miles. The proportion being as three to one in favor of the Virginia port." * * * "The natural advantages, then, in relation to the sea or the back country, are superior, beyond comparison, to those of New York."

There is little, if any exaggeration in this estimate; yet, if a deadly, enervating pestilence had always raged here, this Norfolk could not be a more miserable, sorry little seaport town

Page 138

than it is.*

* This was written and printed long before the late sad visit of yellow fever to Norfolk. I should hardly let it stand now, if I had not previously thought and said, when in the town, that its undrained and filthy condition was such that it seemed to me incredible that its people could live in health. If the condition of the town, at the time of my visit, was not very extraordinary, this dreadful visitor certainly did not come uninvited.

Since writing this note, my attention has been called to an article in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, written by a person who had resided for two years in Norfolk, and who says the town is "destitute of sewerage, and its streets are extremely filthy, being often strewed with refuse vegetables and other garbage, which result from the immense quantity of provisions brought into the city for export. These matters become rotten, and emit a most noisome stench. The turkey-buzzard, the natural scavenger of the South, is not found in Norfolk, but his place is supplied by cows, who wander at will through the town, and gather an unhealthy subsistence from the cabbage-stalks and other substances which lie in heaps on the ground. The condition of Portsmouth is much worse than that of Norfolk. It is connected with Gosport by a causeway, nearly a mile in length, if we are not mistaken, across a swamp or flat, from which arises a powerful stench.

It was not possible to prevent the existence of some agency here for the transhipment of goods, and for supplying the needs of vessels, compelled by exterior circumstances to take refuge in the harbor. Beyond this bare supply of a necessitous demand, and what results from the adjoining naval rendezvous of the nation, there is nothing.

Singularly simple, child-like ideas about commercial success, you find among the Virginians--even among the merchants themselves. The agency by which commodities are transferred from the producer to the consumer, they seem to look upon as a kind of swindling operation; they do not see that the merchant acts a useful part in the community, or, that his labor can be other than selfish and malevolent. They speak angrily of New York, as if it fattened on the country without doing the country any good in return. They have no idea that it is their business that the New Yorkers are doing, and that whatever tends to facilitate it, and make it simple and secure, is an

Page 139

increase of their wealth by diminishing the costs and lessening the losses upon it.

They gravely demand why the government mail steamers should be sent to New York, when New York has so much business already, and why the nation should build costly custom-houses and post-offices, and mints, and sea defenses, and collect stores and equipments there, and not at Norfolk, and Petersburg, and Richmond, and Danville, and Lynchburg, and Smithtown, and Jones's Cross-Roads? It seems never to have occurred to them that it is because the country needs them there, because the skill, enterprise and energy of New York merchants, the confidence of capitalists in New York merchants, the various facilities for trade offered by New York merchants, enable them to do the business of the country cheaper and better than it can be done anywhere else, and that thus they can command commerce, and need not petition their Legislature, or appeal to mean sectional prejudices to obtain it, but all imagine it is by some shrewd Yankee trickery it is done. By the bones of their noble fathers they will set their faces against it--and their faces are not of dough--so they bully their local merchants into buying in dearer markets, and make the country tote its gold on to Philadelphia to be coined; and their conventions resolve that the world shall come to Norfolk, or Richmond, or Smithtown, and that no more cotton shall be sent to England until England will pay a price for it that shall let negroes be worth a thousand dollars a head, &c., &c., &c.

Then, if it be asked why Norfolk, with its immense natural advantages for commerce, has not been able to do their business for them as well as New York; or why Richmond, with its great natural superiority for manufacturing, has not prospered like

Page 140

Glasgow, or Petersburg like Lowell--why Virginia is not like Pennsylvania, or Kentucky like Ohio?--they will perhaps answer that it is owing to the peculiar tastes they have inherited; "settled mainly (as was Virginia) by the sons of country gentlemen, who brought the love of country life with them across the Atlantic, and infused it into the mass of the population, they have ever preferred that life, and the title of country gentleman, implying the possession of landed estates, has always been esteemed more honorable than any other."*

Compare with 17th century description.

* Dr. Little's History of Richmond.

It is simply a matter of taste"

Source:

Frederick Law Olmsted Sr., A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, 1853-1854.