The early twentieth century in Russia was characterized by frenzied artistic activity and creativity. Inspired by a close association with and increased exposure to current European artistic styles, the Russian avant-garde artists reinterpreted these styles by combining them with their own unique innovations. No longer did the Russians simply follow Europe's lead; now they initiated new and exciting artistic experiments which would ultimately change the face and the direction of modern art.

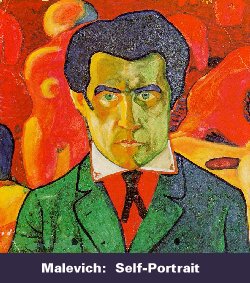

The culmination of this period's developments can be found in the idea of abstract, non-objective (non-representational) art. Finding perhaps the most definitive expression in Kazimir Malevich's Suprematist works, abstract art developed through a series of artistic experiments, which, though usually short-lived, were crucial to its genesis. These experiments (movements) included Neo-primitivism, Rayonism (Rayism, Rayonnism), Cubism, Cubo-futurism, Suprematism, and Constructivism. Some of the most important representatives of these movements were Goncharova, Larionov, Malevich, Popova, Tatlin, Rodchenko, Rozanova, Udal'tsova, Lentulov, Kliun, and Matiushin. Among the other artists, more difficult to classify or to "compartmentalize," were Filonov, Kandinskii, and Chagall; they stood apart from the rest not so much because of the essential direction of their works as because of their methods and particular sources of inspiration. Embodied in the rise and fall of these artistic currents, "the idea of renewal of art as a socially active force" remained strong (Gray, 280) and served as a unifying factor for the artists of the Russian avant-garde.

The culmination of this period's developments can be found in the idea of abstract, non-objective (non-representational) art. Finding perhaps the most definitive expression in Kazimir Malevich's Suprematist works, abstract art developed through a series of artistic experiments, which, though usually short-lived, were crucial to its genesis. These experiments (movements) included Neo-primitivism, Rayonism (Rayism, Rayonnism), Cubism, Cubo-futurism, Suprematism, and Constructivism. Some of the most important representatives of these movements were Goncharova, Larionov, Malevich, Popova, Tatlin, Rodchenko, Rozanova, Udal'tsova, Lentulov, Kliun, and Matiushin. Among the other artists, more difficult to classify or to "compartmentalize," were Filonov, Kandinskii, and Chagall; they stood apart from the rest not so much because of the essential direction of their works as because of their methods and particular sources of inspiration. Embodied in the rise and fall of these artistic currents, "the idea of renewal of art as a socially active force" remained strong (Gray, 280) and served as a unifying factor for the artists of the Russian avant-garde.

After the Revolution of 1917 and the upheavals of the Civil war, war communism, and the New Economic Policy, many artists (for instance Benois) chose to emigrate to the West. Others simply stayed abroad (like Bakst, who left in 1912), sensing the uncertainties and dangers of the future and opting to wait out the storm in the relative safety of their adopted homelands. Those who remained in Russia were initially enticed by the government, particularly by the protection and encouragement extended to them by People's Comissar of Education, Anatolii Lunacharskii, to use their multifaceted talents to create works supportive of the young workers' state. As a result of this encouragement, the first ten years after the Revolution saw amazing developments in literature, painting, and theater. Despite or, perhaps, because of endless debates about the role of arts and artists in the new Soviet society, artists were relatively free to experiment, to establish their own unique styles and to join one of a great number of art groups and organizations. However, by 1928, this initial support for the arts was no longer necessary. The Soviet Union survived and matured, despite the attempts of the counter-revolutionaries and foreign interventionists to bring the tsarist Russia back. Now it was time to start turning the intellectuals into obedient puppets glorifying the leader (Stalin), the Party, and the state. In 1928 all independent art organizations were closed and the work to define the official Soviet artistic method began. Lunacharskii was replaced. The preparations ended in 1934. The first Congress of the Soviet writers established the doctrine of socialist realism (applicable to all the arts), which was to remain the officially approved artistic method until the dramatic changes initiated by the reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev swept it into the dustbin of history. [A.B., B.B. and C.B.]