Humanities, East Campus

|

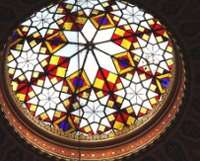

My Reactions to the Humanities in Eastern Europe Institute The most dominant perception that I attained through our classes, reading, and travel in Eastern Europe was an awareness that the people of Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland, see the recent history in terms of what life was like under Soviet domination and what it is becoming now that they are free of that domination. This awareness was derived from lectures and materials given by our guest scholar, from conversations with our Hungarian guide, Réka, from my observations in those countries, and from information provided by our local guides. Every event of the last half century seemed to be cast in terms of what conditions were under the Soviets and what these cities and societies are making themselves into now, approximately ten years after casting off the foreign domination. The buildings themselves seemed to speak of neglect or restoration: renovated or not yet restored. The shopkeepers seemed to brim with an enthusiasm for entrepreneurship. At the same time, it was clear that these people have happily chosen to keep some of the socialist benefits: medical care, inexpensive public transportation, and plentiful staffing for the museums. Another perception that I gained via the Institute was a greater understanding of how “fluid” the borders of Eastern European countries have been throughout the centuries. Resentment towards the domination of the Germanic/Austrian culture became apparent as I learned about the experience of the Czech and Hungarian people. For the Hungarians, that resentment of outside control was also extended toward the Turks, although they had, at the same time, adopted elements of Turkish art into their art and architecture. I have long been aware of the Poles’ resentments regarding foreign domination, but traveling in Poland made me more aware of how the Poles were victimized various times and yet, at the same time, managed to preserve a strong sense of national identity, as well as preserving their national treasures in Krakow. Another gratifying aspect of the travel was my enhanced awareness of the artistic achievements of Eastern Europeans, which are certainly comparable to those of the artists of Western Europe, with whom I had been more familiar. I was definitely aware of the musical achievements of composers such as Chopin, Liszt, Mozart and Smetana, as well as the literature of Russian authors, but the achievements of Eastern Europeans in painting, sculpture, and architecture were largely unknown to me. I am grateful for an expanded consciousness.

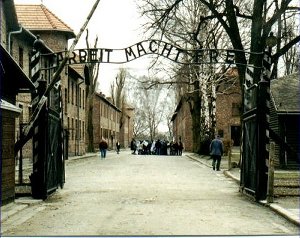

Visiting Auschwitz was sobering; it made the Holocaust seem both more “real” and unreal since the place itself was bathed in a luxuriant summery green when I was there. At the same time, it was enlightening to see many of the sites connected with the flourishing Jewish culture that existed in Europe prior to the Holocaust. I was again reminded of how Europeans seem both to fear the gypsy culture and yet are fascinated by it. Once again, I was reminded that Europeans and their governments value the arts more than we do here in the U.S., much to my regret. Visiting these three countries has whetted my appetite for seeing more of Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe; I very much want to visit Rumania and Transylvania, the former East Germany, Austria, and Russia! The Institute will certainly enhance my teaching and enlarge the scope of my reading. |

I

realize now how hard Eastern

Europeans are working to catch up with the economies of their

neighbors in Western Europe(I couldn’t help but be impressed with the number of people

heading to work at 6 AM and considering working a twelve-hour day

something normal rather than extraordinary).

I

realize now how hard Eastern

Europeans are working to catch up with the economies of their

neighbors in Western Europe(I couldn’t help but be impressed with the number of people

heading to work at 6 AM and considering working a twelve-hour day

something normal rather than extraordinary).