Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane, 1956.

We may be “unconsciously nourished by the memory of the sacred.”

In illo tempore, the perpetual re-enactment of the origin (dithyramb was the re-enactment of the Dionysian)

Openness to the world (risky and insecure outcome).

"Discover the possible dimensions of human existence."

p. 15.

Heidegger's four universal, precognitive, underlying–virtually inherent–human configurations.

| Sky | ||

| divinities |  |

mortals |

| Earth |

Question:

What have we forgotten that appears to us over and over again?

Goya's conception of the myth Kronos devouring his children.

Contents:

Contents:

- Sacred Space and Making the World Sacred

- Sacred Time and Myths

- The Sacredness of Nature and Cosmic Religion

- Human Existence and Sanctified Life

Space, time, nature, & the cosmos

are

sacral as well as profane

sacral: that sacred quality that is universally manifesting some eternal or nearly eternal quality

The etymology of religio, the radical root of religion, meaning a loosely or an organized expression of faith

Religion

religio re (again) lig (tie) [religare to tie fast Latin]

“anyone seeking to discover the potential dimensions of human existence.”

“The abyss that divides the two modalities of experience –sacred and profane—will be apparent when we come to describe sacred space and the ritual building of the human habitation, or the varieties of religious experience of time, or the relations of religious man to nature and the world of tools, or the consecration of human life itself, the sacrality with which humankind’s vital functions (food, sex, work and so on) can be charged.”

14

“The reader will very soon realize that sacred and profane are two modes of being in the world, two existential situations assumed by humankind in the course of… history."

"But for the primitive, such an act is never simply physiological; it is, or can become, a sacrament, that is, a communion with the sacred.”

Ibid.

Eliade’s Source:

Rudolf Otto’s, Das Helige, The Sacred, 1917

“the content and specific characteristics of religious experience….he concentrated chiefly on its irrational aspect.”

{as opposed to rational religion}.

“Luther’s God…not the God of the philosophers, …Erasmus….It was a terrible power, manifested in the divine wrath.”

8

Numinous, numen = god

“The numinous presents itself as something ‘wholly other’ (ganz andere), something basically and totally different.”

8-9

Numinous refers in Otto's work as a power inherent in divinity to both attract and repel, for the divine to both induce fear and to so fascinate as to compel us to another level of response.

The reactions we have are almost antithetical because of the force displayed, perceived, or in some way expressed.

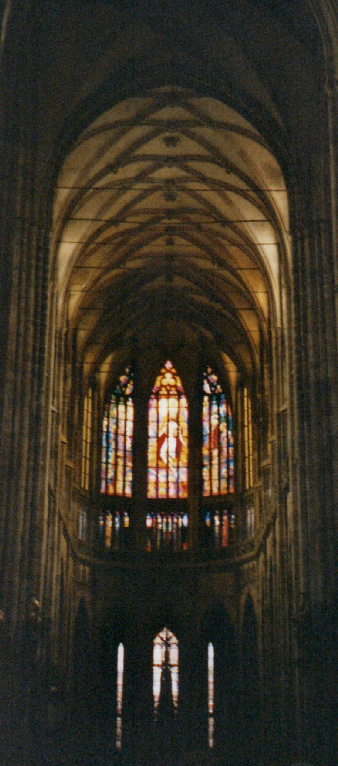

![]() Chapter 1: Sacred Space and Making the World Sacred, pp. 20-65.

Chapter 1: Sacred Space and Making the World Sacred, pp. 20-65.

“ It must be said that the religious experience of the nonhomogeneity of space is a primordial experience, homologizable to a founding of the world.”

Homo as he uses it here means the same, or similar, that is possessing a similarity to something. Here Eliade's terms should not get in the way of your seeing how he combines two opposites; hence there is in the world we experience different spaces -- called by Eliade "nonhomogeneity" but in the the sense that religion or the ritual expression of the apprehension of the divine in existence, we can detect a similarity between the birth or founding of the world.

This is what he means by "an ability to make differences disappear in a certain similarity" –hence the the use of the word homologizable– being capable of becoming similar. A manifestation of sacredness is that we associate particular places we inhabit with the origins of creation.

“For it is the break affected in space that allows the world to be constituted because it reveals the fixed point, the central axis (axis mundi) of future orientation.”

When the sacred manifests itself in any hierophany – [the display of the sanctified, holy, divine]

20-21

“To exemplify the nonhomogeneity of

space as experience by nonreligious man, we may turn to any religion.

“the door that opens to the interior of the church actually signifies a

solution of continuity.”

pp. 24-25.

Two modes of being: the profane and the religious.”

p.25

passing the domestic threshold and the rites associated with it.

“Opening, door. Threshold. Gateway, aperture, hole,

the church – Narthex and apse

24-25

“Properly speaking, there is no longer any world, there are only fragments of a scattered universe, an amorphous mass consisting of an infinite number of more or less neutral places in which humankind moves, governed and driven by the obligations of an existence incorporated into an industrial society.”

24

“Our primary concern is to present the specific dimensions of religious experience, to bring out the differences between it and profane experience of the world.”

17

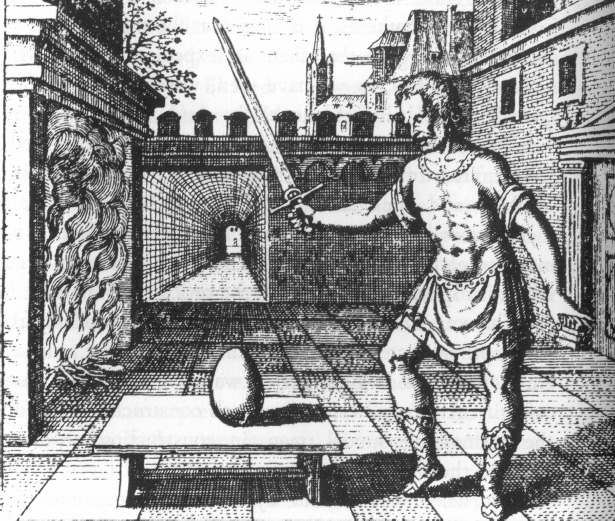

pp. 25-26.

Identity of the sign of divine sanction, springs, the stick, and a tree sprouting overnight from that action, 16th century

27

opposition of chaos and cosmos – order of things

29

The Vedic ritual of taking possession by erecting an altar of fire (Zoroastrian)

30

Repetition of the cosmogonic origin of: order, direction, meaning, purpose

32

Axis mundi, the center of the world -- Kwakiutl chant / shout

36

Temple basilica cathedral is a reproduction of the celestial architecture, the imago mundi – a preconfiguration in the manifestation of space and stone

58

Concluding remarks on chapter 1: Sacred space

“The experience of sacred space makes possible the ‘founding of the world,’ where the sacred manifests itself in space; ‘the real unveils itself,’ the world comes into existence.”

63

“the world becomes apprehensible as world, (wholly

related in meaning) as cosmos, in the measure in which it reveals itself as

a sacred world. [orderly

transcendent and partaking in the divine]

![]() Chapter 2: Sacred Time

and Myths.

Chapter 2: Sacred Time

and Myths.

68

endless recapitulation of the origin, is actually Parmenidean time; after Parmenides' concepts

“Hence sacred time in indefinitely recoverable, indefinitely repeatable.”

69

Yokuts, world = cosmos = year all the same

73

• Periodically becoming contemporary with the gods

“man desires to have his abode in a space opening upward, that is, communicating with the divine world.”

91

"…what matters is to remember the mythical event."

Cannibalism,

"It is at this stage of culture we encounter ritual cannibalism.

"symbolically the same as harvesting..."

"the human responsibility assumed by the cannibal."

102

"The food plant is not given in nature; it is the product of slaying, for it was thus that it was created in the dawn of time."

"...cannibalism is not a 'natural' behavior in primitive man; It is a cultural behavior based on a religious view of life."

pp. 102-103.

“the liturgical time of the calendar flows in a closed circle” a ‘succession of eternities’ periodically recoverable.”

104

the world recreated

105

imitatio dei -- to participate in being with the gods to recover

the divine

"The sacred calendar annually repeats the same festivals....Strictly speaking, the sacred calendar proves to be the 'eternal return'of a limited number of divine gesta– " true for all religions.

106

"that is, when it is desacralized, cyclic time becomes terrifying; it is seen as a circle forever turning on itself, repeating itself infinitely."

p. 107.

![]() Chapter 3: The Sacredness of Nature and Cosmic Religion.

Chapter 3: The Sacredness of Nature and Cosmic Religion.

pp. 116 – 159.

Chapter Three: The Sacredness of Nature and Cosmic Religion.

“nature…is always fraught with religious value.”

(faith, fear, and ideology are wrapped in natural things or processes.)

“it is not chaos, but cosmos,” sacred because it is being “it is there.”

116

The world is here before we are born, hence we say nature precedes us.

The world remains after we pass (as other's pass on), hence we recognize nature outlasts us.

"In this chapter we shall try to understand how the world presents itself to the eyes of a religious person–or more precisely, how sacrality is revealed through the very structures of the world."

p.117.

•The Uranian Gods,

|

celestial objects – | planets, stars, comets & heavely transits |

Named for the Babylonian deities, the planeta–or wandering–bright objects in the night sky took the names of Greek gods.

Only six were apparent to ancient astronomers: Kronos (Saturn), Zeus (Jupiter), Ares (Mars), Aphrodite (Venus), & Hermes (Mercury), the earth was considered Gaia, the mother of the Titans, chthonic beings that preceded the Uranians. |

||

| clouds on Neptune's surface. |

|

|

119

Theophilus of Antioch

“tekméria” the

signs that God has set before them” seasons, days, nights”

136

Tellus mater – earth “mother of us all”

139

• ļ The Desacralization of Nature

151

Read 151-152

accessible to only a few – mostly scientists

– consequence of the 17th century

The Taoist

“This whole complex –water, trees, mountain, grotto – that of the perfect place (mountain) the “completeness with solitude” (Sinai)

153

Cosmos as a tree – eternally fruiting –renewing

148

the tree came to express, everything

157

Jesus as departing from the tree and from human beings (finis)

Chapter 4: Human existence and the sanctified life

Existence open to the world

162

The folklore of European peoples, persistence of the past gods in the clothing of Titans, Olympians, Saints and idols.

163

The sanctification of life

167

Body – house – cosmos

172

pilgrimage to the center of the world.

183

Initiation rites of passage, Marriage socio-sacral recapitulation of heaven and earth telos (the end purpose)

184-84

Initiation ‘s two purposes.

- first completeness

- 2 endurance – feats of strength – re- invoking the ordeal of the culture heroes

187

weltanschauung

211

living the universal

212

division – fall – eclipse – “divided consciousness” a split in the feeling of the self, an estrangement and a bitter exile, un whole, unholy, unfettered from existence

213

Among the Jewish scholars of the middle ages

Maimonides (Hindu, Brahmin to Christian parallelism)

226

Commentary

Before we humans domesticated animals, were we one–instinctually and intuitively–with nature? By that I refer to being one with the herds we followed because we relied on their inherent knowledge of places, we fed on their flesh, acquired their blood, or milk, or hides and relied on the forces of earth, air, wind and rain to sustain the small bands of people.

If so Eliade, in other writings suggests that (& he implies in his book; see page 17, for example.) humans, upon domesticating plants and animals so divided ourselves from the creation that a psychological trauma from which we have never recovered emerged. Here we have then the possibility of one source of religion -- to bind us back to the creation.

Religion may exist to heal the trauma of domestication, when we literally severed and figuratively cut ourselves off from the herds upon which we once depended for order, organization, and survival.

The other reason religion may persist as it does is that it is useful, because, as no mere faith or hope can, all religions instruct people about the value of sacrifice; that is the necessity of doing without something (even life) for the sake of the clan, the others, the world.

![]()

writing | writing about worldviews | practice writing