SCHOLARS EMBARK ON STUDY OF LITERATURE

ABOUT THE ENVIRONMENT

By Karen J. Winkler

The Chronicle of Higher Education, 9 August 1996: page A8+

![]()

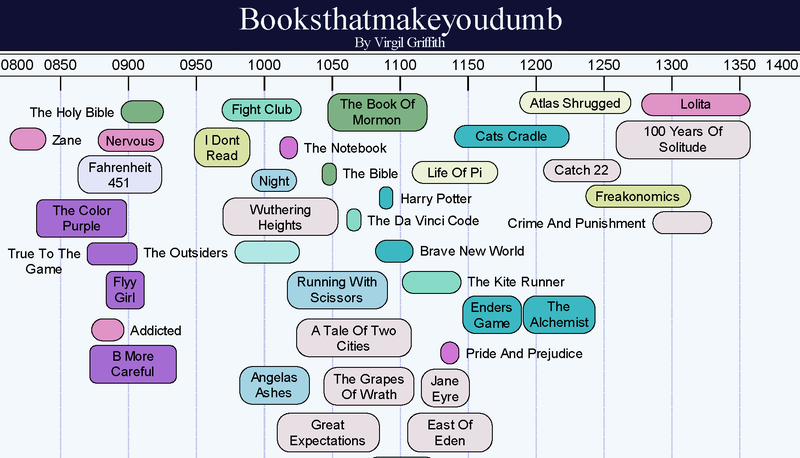

Average SAT (with standard error) for the 100 most popular books on facebook. The vertical axis doesn't mean anything.

The Books has details on the data plotted here. Curious how a particular book acquired its rating? See http://booksthatmakeyoudumb.virgil.gr

Scholars Embark on Study of LITERATURE About the ENVIRONMENT."

Using this article in your writing.

In the late 1980s, Cheryll Burgess was

finishing her dissertation on American women authors when she realized that she

was more interested in another topic – environmental literature.

She was intrigued by

authors from Henry David Thoreau to Edward Abbey who wrote about nature, but she could find no

field of literary criticism devoted to analyzing their writing. True, she came

across scattered books and essays on what she thought of as an ecological

approach to literature, but the authors didn't even seem aware of each other's work.

So she set

about compiling a bibliography of nature writers and the scholars who discussed

them, sending the material to all the names on her list for whom she could find

addresses. She asked them to consider organizing a field, publishing an

anthology, starting a journal. And by the way, she added at the end, she'd like

to become the first professor in the United States with a specific position in

literature and the environment. Anyone interested?

Today, Cheryll Burgess Glotfelty says that "my beginning assumption was that something

we could call ecocriticism was possible, but we would

have to invent the field."

A few years

later, that effort is well under way. This spring the University of Georgia

Press published a survey of the field, The Ecocriticism

Reader, edited by Ms. Glotfelty and Harold Fromm,

an independent scholar. It is just one of many such books that publishers are

adding to their lists. From anthologies of nature writing such as The Norton

Book of Nature Writing (Norton, 1990) to books of literary criticism and

Garland Publishing's upcoming Environmental Literature: An International

Handbook, environmental literature is hot.

Taking

Notice

In 1992 scholars

founded the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (known as ASLE), and it now boasts some 900 members. There's a

journal--ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment--as

well as The American Nature Writing Newsletter (just renamed ASLE News), and an active e-mail discussion list (asle@unr.edu). And yes, Ms. Glotfelty

is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Nevada at

Reno, an institution fast becoming a center for ecocriticism.

At the same

time, the rest of literary criticism is taking notice. Journals such as The

North Dakota Quarterly, The Indiana Review, The Georgia Review, and others have

published special issues on literature and the environment. This year, groups

that meet annually to discuss the literature of Faulkner and Hemingway have

adopted the natural world as their theme.

Still,

nobody is willing to pin down just what ecocriticism

is. Very broadly, scholars say that it adds place to the categories of race,

class, and gender used to analyze literature. For some, that means looking at

how texts represent the physical world; for others, at how literature raises

moral questions about human interactions with nature. Some critics are

resurrecting forgotten texts of nature writing, bringing them into the

classroom and scholarly discussion; others are using post-modern literary theory

to analyze them. Ecofeminists are looking at the way

representations of nature are influenced by gender; environmental activists are

pointing to the ways in which literature addresses ecological problems.

"Green

Cultural Studies"

Scholars

call the emerging field "green cultural studies," "environmental

literary criticism," "the natural history of reading." "The

fact that we can't agree on a name is a sign of the incredible diversity in ecocriticism," says John Elder, a professor of English

and environmental studies at Middlebury College. "It's a free-for-all, and

that's exciting."

The

diversity stems at least in part from the different routes that literary

critics have traveled to ecocriticism. Some literary

critics see their role as raising public awareness of environmental issues.

Many of these scholars were environmental activists before they become ecocritics.

Avid backpackers

have transferred their love of the outdoors to appreciation of its depiction in

literature. Others have responded to the growing interest among literary

scholars in studying non-fiction. Perhaps most important, scholars have been

galvanized by the contemporary renaissance in nature writing among such authors

as Annie Dillard, Barry Lopez, Terry Tempest Williams, and many more.

A number of

literary critics also say that ecocriticism

represents a reaction to the heady theorizing of the 1980s and 90s. They

jokingly call themselves "compoststructuralists,"

to differentiate themselves from poststructuralists and to emphasize the, um,

earthiness of their approach.

"For a

long time, the focus of literary studies was on the world of words," says

Lawrence Buell, a professor of English at Harvard University. From new critics

in the 1950s, who thought that texts could be analyzed on their own terms,

without reference to the context in which they were produced, to recent

theorists who have argued that language never accurately reflects reality,

"there's been a gap between texts and facts," Mr. Buell says.

"But

now there's a recoil: Ecocriticism assumes that there

is an extratextual reality that impacts human beings

and their artifacts--and vice versa."

Not surprisingly,

diversity breeds controversy. When Jay Parini wrote

an article on the new field for The New York Times Magazine last year, he says

that he got over 100 letters--most of them angry.

"People

said that I'd neglected the feminists or ignored the theorists," says Mr. Parini, a professor of English at Middlebury.

"Everybody seems to think that they started ecocriticism."

The Use

of Theory

One of

today's biggest debates is over the use of theory. Scholars such as Glen A.

Love, who has just retired as a professor of English at the University of

Oregon, argue that ecocriticism needs to leave

postmodernism behind. Environmental studies began in the life sciences and then

broadened out to the humanities, Mr. Love says, but the two parts of the field

still interact very little.

"As a

literary scholar, it embarrasses me to listen to colleagues who see science as

just a bunch of cultural stories or who talk about nature writing without

knowing very much about nature," he says. "It's time to heal the

breach between the hard sciences and the humanities--and literary theory isn't

going to do it."

Nevertheless,

a number of scholars combine theory and ecocriticism.

In The Ecocriticism Reader, one essay draws on the

theories of Michel Foucault and Edward Said to demonstrate that the environment

is a cultural construct that, for example, ascribes feminine characteristics or

prevailing definitions of innocence to nature.

"It's a

big debate, but I suspect that a lot of people--like myself--are

eclectics," says Mr. Buell. "I sympathize with the view that a stone

is a stone, and no amount of literary theory can change that. But I've also

learned from contemporary theory that we have to watch it when we move from

stone to text. No text can exactly mirror the non-human world."

A related

debate focuses on whether ecocriticism is compatible

with feminist theorizing and analysis. Clearly, ecofeminism is an up-and-comer,

with its own special issue of ISLE in the works and numerous anthologies of

women nature writers already published.

Reflections

of Gender

Yet Louise

H. Westling, a professor of English at the University

of Oregon, worries that by emphasizing the way gender is reflected in

depictions of the landscape, ecofeminism reinforces a long-standing tradition of

assuming that the land is female and the people who affect it male.

"That's absurd. The land is not a woman. But from ancient times, writers have used feminine images to justify conquering it," says Ms. Westling. Academic analysis sometimes jars on environmental activism.

What is

Nature?

"A lot of ecocritics thought that kind of

analysis academicized the discussion in ways that

debunked the efforts of conservationists and could be manipulated by

developers," says Scott Slovic, editor of ISLE

and director of the Center for Environmental Arts and Humanities at the

University of Nevada at Reno.

Other

questions abound:

What is

nature--and where does one find it? The Association for the Study of Literature

and Environment started at a meeting of the Western Literature Association, and

some of the most prominent departments in ecocriticism

are in the West--at Reno, the University of Oregon, the

University of California at Davis. Perhaps as a result, a lot of ecocriticism has focused on Western literature. But Mr.

Tallmadge, a professor of literature at Cincinnati's Union Institute, asks:

"Do you have to just read John Muir and his encounters with the Sierras?

Can't you read John Updike on the city and talk about place and location in

terms of urban environments?"

What is

nature writing? Traditionally, scholars have thought of it as the non-fiction

essay popularized by Thoreau, a blend of scientific observation and

self-analysis. But the writer Annie Dillard recently set off a furor on ASLE's e-mail network when she confessed to a writing

seminar that she had made up a number of descriptions and incidents in her

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, which describes her life in a valley of Virginia's

Blue Ridge Mountains. If you can't trust a nature writer, some scholars asked, who can you trust? Nevertheless, a number of scholars are

calling for a broadened definition of nature writing, one that includes poetry and fiction.

Are nature

writing and ecocriticism a middle-class preserve? Most critics would say Yes. So far, nature writing and

the scholarly discussion of it have centered primarily in Europe and North

America, attracting people who have the leisure and money to go out and enjoy

nature. But some literary critics say they should study how other

traditions--for example, the oral stories of American Indians--represent

nature. Moreover, scholars such as Mr. Slovic are

trying to spread ecocriticism abroad: While on a

Fulbright fellowship to Japan a few years ago, he helped establish ASLE-Japan, which now boasts more than 100 members. This

month the group is sponsoring an international symposium in Hawaii on Japanese

and American nature writing.

Do nature

writers and the ecocritics who study them take themselves

a bit too seriously? A number of literary critics are experimenting with nature

narratives, blending their personal experiences, for example in the woods of

Maine, together with their readings of poets such as Robert Frost, who

described those locations.

The Western

writer C.L. Rawlins recently poked fun at this kind

of introspection in an article in The Bloomsbury Review, dubbing it "the

gentle thunder of a well-beaten breast." "Sitting at the desk with

PowerBook, herb tea, and a stack of index cards, one suddenly realizes that

upon reaching that farthest, highest peak, instead of eating a sandwich one in

fact saw God," he wrote.

"Do we

always have to come back to ourselves?" asks Oregon's Ms. Westling. "Surely nature writers and ecocritics ought to be looking for a less androcentric

approach."

A Scathing Satire

Outside

of ecocriticism, the reaction to the field is mixed.

Mr. Parini's New York Times article provoked a

scathing satire in The Washington Post. Jonathan Yardley, a Post columnist,

echoed the thoughts of some English professors when he dubbed ecocritics "just another passel of academics who've figured out how to turn the classroom into a

political forum."

Some among

the ranks of literature's theorists also voice qualms. Donald E. Pease, a professor

of English at Dartmouth College, worries that "the turn to nature can

spawn an attitude of rugged individualism that is escapist and narrow. It still

needs to be affiliated with other kinds of emancipatory literary

practice."

Indeed, in

some ways ecocriticism still hasn't quite broken into

the mainstream. Phyllis Franklin, executive director of the Modern Language

Association, says that preliminary plans for the association's next annual

meeting show few sessions in the field. She adds, however,

that "I do know people working on books that will appear in the

academic marketplace in the future. That's when this approach will have more of

an impact."

Scholars

such as Harvard's Mr. Buell say that "the worst

thing that could happen would be for ecocriticism to

become just another branch of literary criticism. I would hope that we

could continue to have meetings where smart dropouts and backpackers talk to

tenured professors."

What is ecocriticism ?

1. it adds place to the categories of race, class, and gender used to analyze literature.

2. that means looking at how texts represent the physical world;

3. at how literature raises moral questions about human interactions with nature.

4. resurrecting forgotten texts of nature writing,

4.1 bringing them into the classroom and

4.2 scholarly discussion;

5. using post-modern literary theory to analyze texts.

6. Ecofeminists are looking at the way representations of nature are influenced by gender;

7. environmental activists are pointing to the ways in which literature addresses ecological problems.

ecological literacy, defining the term

ecological terms and their meaning

Using this article in your writing.

![]()

Key Works, Recent Books, and Anthologies in Ecocriticism

Sisters of the

Earth: Women's Prose and Poetry About Nature, edited by Lorraine Anderson

(Vintage, 1991)

Romantic Ecology: Wordsworth and the Environmental Tradition, by Jonathan Bate (Routledge, 1991)

The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the

Formation of American Culture, by Lawrence Buell (Harvard University Press,

1995)

Imagining the Earth: Poetry and the Vision of Nature, by John Elder (University

of Illinois Press, 1985)

The Norton Book of Nature Writing, edited by Robert Finch and John Elder (W.W. Norton

& Company, 1990)

The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary

Ecology,

edited by Cheryll Glotfelty

and Harold Fromm (University of Georgia Press, 1996)

Ecological Literary Criticism: Romantic Imagining and the Biology of

Mind, by

Karl Kroeber (Columbia University Press, 1994)

This Incomperable Lande:

A Book of American Nature Writing, edited by Thomas J. Lyon (Houghton Mifflin

Company, 1989)

The Comedy of Survival: Studies in Literary Ecology, by Joseph W. Meeker

(Scribner's, 1972)

Wilderness and the American Mind, by Roderick Frazier Nash (third edition, Yale

University Press, 1982)

Made From This Earth: American Women and Nature, by Vera Norwood

(University of North Carolina Press, 1993)

The Idea of Wilderness: From Prehistory to the Age of Ecology, by Max Oelschlaeger (Yale University Press, 1991)

Pilgrims to the Wild: Everett Ruess, Henry

David Thoreau, John Muir, Clarence King, Mary Austin, by John P. O'Grady (University of Utah Press,

1993)

Seeking Awareness in American Nature Writing: Henry Thoreau, Annie

Dillard, Edward Abbey, Wendell Berry, Barry Lopez, by Scott Slovic (University of Utah Press, 1992)

The Practice of the Wild, by Gary Snyder (North Point Press, 1990)

The

Green Breast of the New World: Landscape, Gender, and American Fiction, by Louise H. Westling (University of Georgia Press, 1996)

This article was at: http://www.asle.org/site/resources/ecocritical-library/intro/embark/