Internal clocks

"Seeing our connections to the natural world is like detecting the pattern hidden in an optical illusion."

p. 4. Neil Shubin, The Universe Within. 2013.

"Our good fortune . . . is just a moment in time." 1

The trigger of light, the pineal gland, and luminist artists.

"This reaction – from light to the brain to the pineal gland to melatonin and its triggers across the body – tunes our bodies to the light of the day, and the darkness of night."

page 76.

"We live in an age of disconnect between the ancient rhythms inside us and our modern life."

page 77.

"Humans are a timekeeping species, and much of our history can be traced to the way we parse moments of our lives. These intervals are based as much on astronomical cycles as on our needs, desires, and the ways we interact with one another."

"the DNA in our bodies can serve as a kind of timepiece. Averaged over long periods of time, changes to some parts of the DNA sequence happen at a relatively constant rate."

page 60.

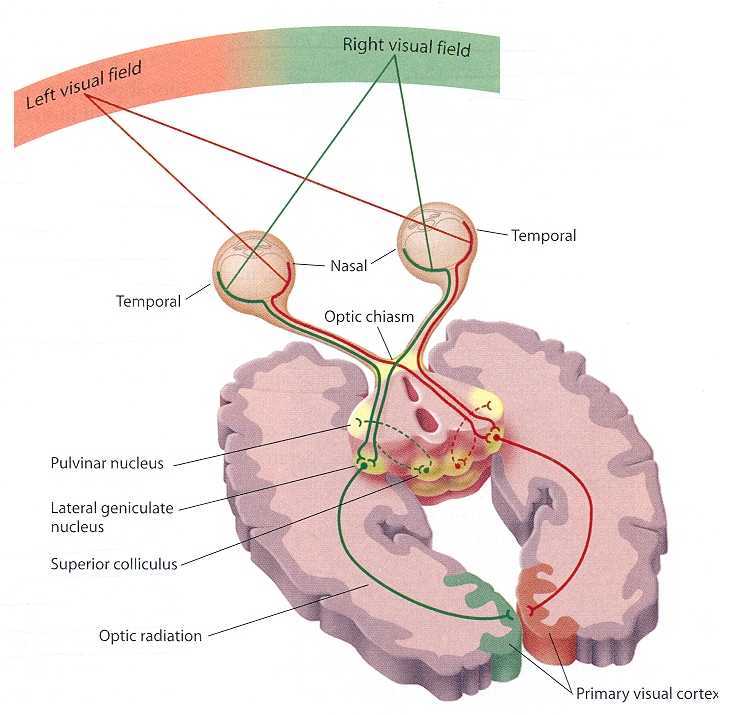

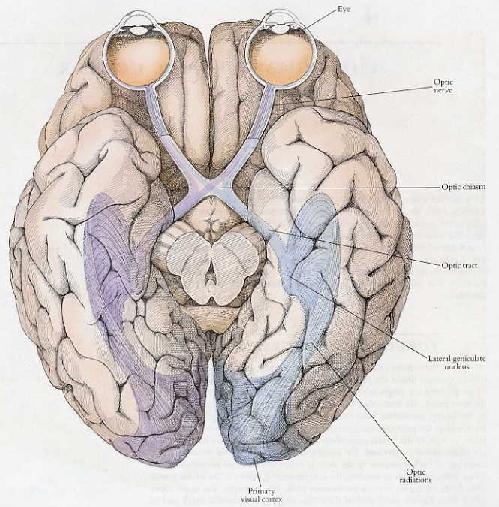

"Our cellular clock is tuned to the outside world by a number of triggers, the most important of which is light."

Page 76.

Solar radiation

![]()

Sun exposure to radiant energy is the source of electromagnetic waves striking the earth that plants convert into mass and that humans, like other animals, respond to in terms of timing. Light is what we commonly call these visible electromagnetic waves.

Plants such as trees, use light to grow; these concentric and sequential rings of this tree reveal the conditions of the landscape in which it thrived. These conditions are understood in terms of solar exposure, water, nutrients and temperature in the place it once grew. The wider apart these rings are, the more moisture and nutrients that were available, and the narrower the distance between two rings the fewer nutrients and drier the conditions that year. By counting the annual rings, one may determine the age of the specimen. The age of this tree –for example– has to be older than seventy-five years before it was cut.

The diurnal pace of the pineal gland

Circadian rhythms in humans –as these changes in somatic responses are called– are actual examples of feedback.

Illustrated on page 77.

Dorsal

The pineal gland is at the back of the brain about the size of a small cashew nut lying behind the optic chiasm and situated at the dorsal end of the roof of the third ventricle set above the brain stem.

| A contingent cascade of coupled responses. | ||

Light |

||

|

||

Secretion of melatonin molecule (a hormone) |

Richter's patch of brain cells (tissues). |

|

Pineal gland |

||

"Most of the light that enters our eyes ends up as a signal to the parts of our brain that interpret visual information. Some of these signals, though, get sent to a different part of the brain–to Richter's patch of cells. The path from Richter's patch travels to a little pea-sized gland (a part of the endocrine system) at the base of your brain called the pineal."

page 76.

Waves in a sea of electrons.

![]()

"Light is among the least understood forms of energy. Yet light or radiant energy is the most prolific experience of our lives. That experience is shared by virtually all but those who are blind from birth. The analogy of light revealing some important facets of our daily experience has seeped into our literary expression as metaphors and the entire conception of what it means to overcome ignorance and emerge as "enlightened."

Shubin insists that:

"Train the eye and these familiar entities give way to deeper realities. When you learn to view the world through this lens, bodies and stars become windows to a past that was vast almost beyond comprehension, occasionally catastrophic, and always shared among living things and the universe that fostered them."

"Knowing how to find past life means learning to see rocks not as static objects but as entities with a dynamic and often violent history. It also means understanding that our bodies, as well as our entire world, represent just moments in time."

p. 4. Neil Shubin, The Universe Within.

"The rocks also tie us to the past; rifts in Earth, like those that led us to find fossil mammals . . . , have left traces in our bodies as much as they have on the crust of the planet."

p. 13. Neil Shubin, 2013.

"Rocks and bodies are kinds of time capsules that carry the signature of great events that shaped them. The molecules that compose our bodies arose form stellar events in the distant origin of our solar system. Changes in the Earth's atmosphere sculpted our cells and entire metabolic machinery. Pulses of mountain building, changes in orbits of the planet, and revolutions within Earth itself have had an impact on our bodies, minds, and the way we perceive the world around us."

p. 14. Neil Shubin, 2013.

Next.

![]() Sources:

Sources:

![]()

The quotation is from page 59.

1) Neil Shubin, The Universe Within: The Deep History of the Human Body. New York, Random House, 2013.

Background

"200-million-year-old link between reptiles and mammals."

p. 4. Neil Shubin, The Universe Within. 2013.

![]()

Shubin's ideas:

"Inside every organ, cell, and piece of DNA in our bodies lie over 3.5 billion years of the history of life. . . "

These are "but gateways to ever deeper connections . . . .

"Written inside us is the birth of the stars, even the origins of the days themselves."

page ix.

Rocks reveal the deep past hidden from our view

The fossils in our bones "The relative proportion of atoms is only part of what defines our bodily structure."

Years before now & their related events

4,600,000,000 "We are relative newcomers to this party. By 'we' I mean our entire solar system."

4,500,000,000 "There was no moon."

2,400,000,000 "a long period of relative quiescence."

200,000,000 "The modern world came about through changes to rock, air, water, & life"

65,000,000 "Land, water, and air were populated by an entirely different world of creatures, all of them successful by every yardstick we can apply . . . ."

40,000,000 "Antarctica was once a warm and wet world teeming with tropical life."

10,000 "Ice ages" precession of the equinoxes and Milankovitch cycles

bodies | rocks | oxygen | conclusions

The unimaginable luck of life.

"We are a very select mix of atoms. . . . we are virtually unique in the known universe."

p. 15

"Bodies are organized like a set of Russian nesting dolls: tiny particles make atoms, groups of atoms make molecules, and molecules assemble and interact in different ways to compose our cells, tissues, and organs."

page 16.

"A critical insight of modern biology is that our family history extends to all other living things."

"Unlocking this relationship means comparing different species with one another in a very precise way. An order to life is revealed in the features creatures have: closely related ones share more features with one another than do more distantly related."

Parts of the human endocrine system arose early in boned fishes.

"The reason is that fish, like people, have backbones, skulls and appendages."

p. 17.

Some rocks are tomes of evidence:

"Every rock in the ground is an artifact that, when you know how to interpret it, becomes a time capsule, a thermostat, even a barometer of the health of the planet. To wrest details from the stones, we have to zoom from a bird's eye view of rock layers all the way down to a microscopic one. The smallest components of rocks – the individual grains of sand or minerals inside – often tell the biggest stories."

pp. 40-41.

"The advent of bodies changed the planet forever."

"Bodies may make a dramatic appearance in the fossil record, but if the genomes of living creatures hold any clues, changes were under way for a long time. The first 2.5 billion years of the history of the planet were entirely devoid of big creatures; then, by about 1 billion years ago, there were not one but several different species with bodies populating the ancient seas: plant bodies, fungal bodies, and animal bodies, among others."

"The biological mechanisms needed to build big creatures existed on the planet for billions of years before those creatures ever hit the scene."

pp. 91-92.

"The interplay between living things and their planet led to increasing levels of oxygen in the atmosphere. Oxygen, in turn, changed the world by allowing for the origin of big creatures with many cells. Life changes Earth, Earth changes life, and those of us walking the planet today carry the consequences within."

p. 97.

A Brave New World

"A new world began with the rift, one with ever-rising levels of oxygen. . . . with oxygen come opportunities. Mammals like us are committed to a very high-energy life style. We manufacture our own heat. The action of our muscles, coupled with the insulation provided by our hair & fat . . . keeps our body temperature stable relative to the outside world."

pp. 118-119.

200 Million years ago:

"Moving continents and changing oxygen levels gave the world a decidedly modern configuration by 200 million years ago. . . ."

p. 121.

"Land, water, and air were populated by an entirely different world of creatures, all of them successful by every yardstick we can apply: there were numerous species that thrived for millions of years across wide stretches of the globe. Then they disappeared."

p. 122.

"A forest over 40 million years old . . . ."

"The stumps of that jut out from this frozen landscape expose redwood trees that would have reached heights of 150 feet or more."

p. 141.

The Ice Ages

"Louis Agassiz was born in 1807,

"Giant boulders and gravel mounds told the same story: something was moving these rocks around. But What?"

p. 161.

"In it he proposed the radical notion that ice at one point in time extended from the North Pole all the way to the Mediterranean and then retreated, only to extend again."

"encouraging them to see a past rich in ice."

p. 162.

Revolutionary Apes

"Hints to a revolution afoot are first seen inside rocks about 7 million years old from what are today Chad and Kenya."

"Something was happening, as new kinds of apes lived, and perhaps even walked, on the planet."

p. 179.

"By 8 million years ago, the shapes of the continents, oceans, and seas would be recognizable to an elementary school class today."

p. 179.

Conclusions

Shubin's view of the world forces us to reconsider: landscape, vision as a perception in the act of seeing, and our inherent suppression of stimuli to the contrary. That means we do not often literally see, let alone figuratively understand because we are wearing blinders shaped by our training, conditioning, social rewards, and biases.

Many people suffer from "trained incapacities," as Lynn Margulis had suggested in that we do not see the world as it is; as organisms living together. The biases we nourish in our training emerge from Bacon's familiar four idols that we mistake for genuine knowledge.

Instead of seeing the links (lumpers lump or aggregate together entities that are related) as trained splitters (a splitter sees all these pieces as discrete separate entities with no relation worth describing).

As perceptive animals do all these steps in a process of perception unconsciously, human consciousness has imposed an order on what we perceive. We did so in order to become more alert to changes in our surroundings. But this imposed reordering of perceptions comes at the cost of becoming unable to comprehending more fully this inherently reciprocal relation among things we split into separate entities. Take for example the relation of seeing to light and dark. Joseph Albers the artist showed in his work that what we see depends on the foreground against a background.

Albers "was also one of the first modern artists to investigate the psychological effects of color and space and to question the nature of perception." In Alber's Bauhaus classes "Students not only learned about the interaction of color but to see nuances as well, how the smallest change affected the whole."

Visual ecology

If landscape is a sensory process by which we situate ourselves in space, then vision is a process by which we situate ourselves in time. To the extent that the feedback process of light affecting the pineal gland's secretion of hormones establishes internal cadences tied to external stimuli, this coupling of vision and hormonal release may be understood a primary sense we have of spacetime even though we call this diurnal rise and fall of hormonal levels our biological rhythms.

.gif)