Every scientific activity is characterized by two parts:

Bachelard's paradox | commentary on method | not observed | Lewontin's revelation | dialectic

One is some form of observation, or perception. It can take place directly, through the senses, somewhat more indirectly via some form of an instrument. In one or another respect sense improving instruments like a microscope, a telescope or stethoscope, or even more indirectly via some detecting instrument like a Geiger counter, an electrocardiograph, or an X-ray apparatus (Harré 1976) humans extend our senses to see beyond the surface of our experiences.

One is some form of observation, or perception. It can take place directly, through the senses, somewhat more indirectly via some form of an instrument. In one or another respect sense improving instruments like a microscope, a telescope or stethoscope, or even more indirectly via some detecting instrument like a Geiger counter, an electrocardiograph, or an X-ray apparatus (Harré 1976) humans extend our senses to see beyond the surface of our experiences.

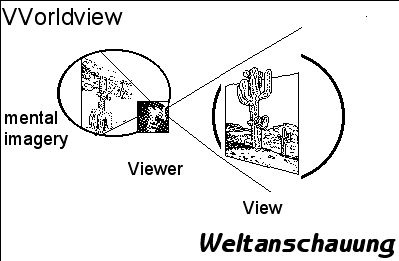

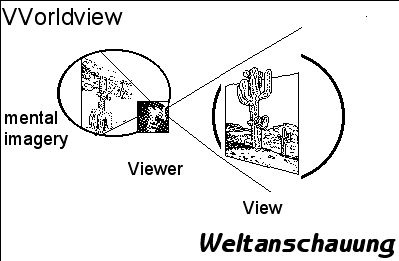

The other part is some form of thought activity. This reflection and evaluation "surrounds" and penetrates the observation/perception, once we define, clarify and analyze the observation into its component parts. A more or less conscious thought activity takes place by the appliocation of reason as an introduction to the observation. It directs the attention in a special direction that is more than just a "point of view."

The other part is some form of thought activity. This reflection and evaluation "surrounds" and penetrates the observation/perception, once we define, clarify and analyze the observation into its component parts. A more or less conscious thought activity takes place by the appliocation of reason as an introduction to the observation. It directs the attention in a special direction that is more than just a "point of view."

To a very signeficant extent, any discovery "chooses" observations on which to focus attention. To examine the choice such an observation intrudes upon us, one must step back during the direct moment of perception or observation. A very real sense of suspending judgment occurs before our preconceptions begin to dominate once more after the direct moment of perception or observation has passed.

The thought activity distinguishes between different parts of that which is observed or perceived. By reasoning our thought process involves language which gives perceptions and observations names. With rational argument further reflection makes a more specific conceptual analysis of what we have discovered. If the discoverd information is of use it will become quantifiable and then related to other discoveries, logically or mathematically.

Scale

Atoms

Genes

Marine Bio blog

defining science

Steve's science web site

Aspects and character of science

Bachelard's paradox | commentary on method | not observed | Lewontin's revelation | dialectic

One is some form of observation, or perception. It can take place directly, through the senses, somewhat more indirectly via some form of an instrument. In one or another respect sense improving instruments like a microscope, a telescope or stethoscope, or even more indirectly via some detecting instrument like a Geiger counter, an electrocardiograph, or an X-ray apparatus (Harré 1976) humans extend our senses to see beyond the surface of our experiences.

One is some form of observation, or perception. It can take place directly, through the senses, somewhat more indirectly via some form of an instrument. In one or another respect sense improving instruments like a microscope, a telescope or stethoscope, or even more indirectly via some detecting instrument like a Geiger counter, an electrocardiograph, or an X-ray apparatus (Harré 1976) humans extend our senses to see beyond the surface of our experiences.  The other part is some form of thought activity. This reflection and evaluation "surrounds" and penetrates the observation/perception, once we define, clarify and analyze the

The other part is some form of thought activity. This reflection and evaluation "surrounds" and penetrates the observation/perception, once we define, clarify and analyze the