Sentimentality

"the landscape"

"the landscape" Navigating the site:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

return to top of the page

The role played by artists, art, and photography in depicting the terrain.

"For many people, there are three basic types of American landscape painting: realistic, impressionistic and abstract. Thomas Cole, Frederick Church and Albert Bierstadt typify the glories of the 'realistic' Hudson River and Rocky Mountain schools; John Twachtman, William Merritt Chase and Childe Hassam typify the glories of the 'impressionist' camp; and Richard Diebenkorn, Georgia O'keeffe and Charles Sheeler typify the glories of the 'abstract' practitioners."

Carter B. Horsley, "George Inness and the Visionary Landscape." The City Review. 2003-2004.

"View on the West Mountain Near Hartford," oil on canvas, c. 1791, by the American artist John Trumbull.

Is photography an art or is it something that imitates a painter's prolonged gestation and difficult portrayal of what it is that they envision from what they are seeing as the sketch, draw, or paint?

"“In photography there is a reality so subtle that it becomes more real than reality.”

“My photographs are a picture of the chaos in the world, and of my relationship to that chaos. My prints show the world’s constant upsetting of man’s equilibrium, and his eternal battle to reestablish it.”

The "city scape"

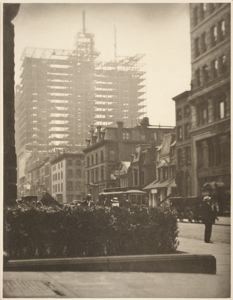

“Picturesque Bits of New York” 1897, 6 x 11. 1894, photogravure from the collection.

“The ability to make a truly artistic photograph is not acquired off-hand, but is the result of an artistic instinct coupled with years of labor.”Alfred Stieglitz, American, 1864-1946

Art critics maintain that "Although Stieglitz showed and published soft-focus pictorial photographs by others, his own work (with a few early exceptions) had always been straight, unmanipulated imagery. When he first began to photograph New York in 1892, he actually worked in the fog or rain to achieve the same atmospheric effects that other pictorialists produced with soft-focus lenses or handwork on the print."

Read more about Alfred Stieglitz Photography 2 by www.leegallery.com.

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

How does defining "landscape" pose a problem for American environmental history?

Native peoples, depicting the geographic variety, and records of transformed terrains are all open to contentious debate over the meaning of land in the nation's history and to what extent landscape values underwent significant changes due to industrial growth. As these changes devolved it can be argued that a clash of perceptions were to have given rise to the tensions inherent in preservation and conservation.

But you must judge the significance of these disagreements in shaping the country's natural and cultural heritage.

Alvan Fisher ( 1792-1863 ) was an early American landscape painter. Born in Boston, Fisher studied under John Ritto Penniman, learning decorative painting techniques. However, Fisher aspired to be an artist and wanted to do more than paint ornamental designs on furniture. Eventually, Fisher taught himself to paint, and had his own studio in 1814.

By 1816 he was creating rural paintings of barnyards and farm life. These paintings were fairly original and unique at the time when the majority of artists were creating portraits and historical scenes. In 1817, Fisher held his first exhibit with the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He also showed his work later on with the National Academy of Design as well as the Boston Athenaeum.

Alvan Fisher, Mishap at the Ford, 1818. Oil on panel, Corcoran Gallery of Art.The painting depicts an accident as the carriage crosses the stream and loses its driver and some baggage. In so doing the painting becomes documentary evidence because the artist's depiction of two major forms of transportation in early America revealing the absence of improved roads or bridges.

Native nations | Geography | Transformation

Native peoples of these varied First Nations where here long before the desires of Europeans and Africans for a new life in an immense geographical arena.

The land was ours before we were the lands.

Robert Frost, The Gift Outright, American Poet.

Introductory: Peoples of the dawn

Arawak woman today & John White's, 1585 water colors of a headman.

Theodore de By, 1598, depicted native customs before European settlements were widespread and to show the destruction of their civilizations by Spanish conquests.

"Many of White's paintings were published, sometimes in altered form, by Theodor de By as etchings in Hariot's illustrated edition of A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1590).

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

Wallace Stegner has referred to the role of wild, unsettled, and less-populated terrain in the historical development of American culture as exhibiting a "geography of hope," in that people generation upon generation invested in the landscape with unquenchable desires. Such unbounded enthusiasm for some countryside to afford them a livelihood, if not security is not unknown in other civilizations, but rises to a fever pitch in American life. As Stegner saw it, "We simply need that wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in. For it can be a means of reassuring ourselves of our sanity as creatures, a part of the geography of hope."

He clearly implied that there needed to be a counterpart to possession if possessing the land was to have any meaning and if by possessing the land as real-estate we did not end up converting the vaster expanses into slag wastes of the industrial habits of extraction and consumption.

So in the art, cartography and photography of the American past, the goal is to discern to what extent geography informs if not determines the sort of culture, the kind of values, and the conditions of terrain that we pass from one generation to the next.

| Representations of the Novus mundi, or "new world" | ||

|

|

|

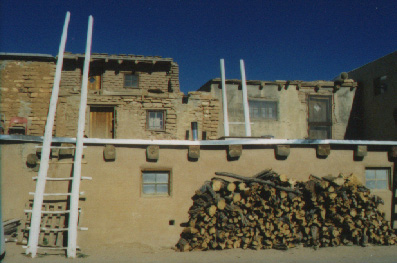

| Anasazi Kiva | Middle Ages spilled into the Renaissance | |

|

|

|

Incipient nationalism: By saying that the Middle Ages spilled into the Renaissance in North America, we mean long-held attitudes persisted and in the sense that European settlement of new land, so vital to populations of the Medieval period was still so important that with Columbus' discovery these attitudes became precursory behavioral standards.

These older experiences informed the European responses to the demands of the New World. Older precedents had shaped the behavior, attitudes, customs, and laws that Europeans imposed on Native Americans changing the landscape from a source of fruition and sustenance to a contested ground of property and commercial gain. With no other experience of settling less populated terrains and countryside, the Europeans repeated patterns of behavior and regulations that had once served them well in previous centuries.

- John White, unknown -1593.

- John Trumbull, 1759-1845.

- Washington Allston, 1779-1843.

- Alvan Fisher, 1792-1863.

- George Catlin, 1796-1872.

- Asher B. Durand, 1796-1886.

- Thomas Cole, 1801-1848.

- Martin Johnson Heade, 1819-1904.

- Frederic Edwin Church, 1826-1900.

- Albert Bierstadt, 1830-1902.

- Winslow Homer, 1836-1910.

- John Henry Twachtman, 1853-1902.

- Alfred Stieglitz, 1864-1946.

- Georgia O'keeffe, 1887–1986.

- Charles Sheeler, 1883-1965.

- Helen Frankenthaler, 1928 -2011.

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

![]()

The European contact: the watercolors of John White.

John White's (ca.1540 - 1593) contribution to our understanding of early America rests on the magnificent watercolor paintings and sketches he made of native Virginians and their culture during the 1580s.

Because the native Americans were largely obliterated from the eastern woodlands by 1790, White's watercolors are our only indication of the population's character and style with respect to ceremonies, clothing, behavior and village life.

The illustrations gave sixteenth-century Europe its first extensive pictorial views of the physical characteristics of the New World. White was a member of the 1585 expedition to Virginia by his half-brother Sir Walter Raleigh. The expedition established on Roanoke Island the earliest Virginia colony, where White painted the native Algonquian Indians, flora, and fauna of the area. In 1587 White returned to Roanoke as governor of the colony and made several voyages back and forth to London to bolster the fledgling enterprise.

Early America scenic wonders and quiet places

While some of the depictions appear to be unrealistic, many artists sought to convey the conditions of the world they saw and heard around them.

John Trumbull and the birth of romantic landscapes of historical note.

Harvard Museum's collection. includes two 1783 sketches.

Other landscape works by the American artist John Trumbull known for his portraits of Federalists & historical events.

Romantic Landscape, oil on canvas painting by John Trumbull, c. 1783, Dayton Art Institute.

"View on the West Mountain Near Hartford," oil on canvas, possibly 1791; Yale University Art Gallery.

"Norwich Falls (or The Falls on the Yantic at Norwich)," oil on canvas, 1808; Yale University Art Gallery.

In 1825 Trumbull bought Thomas Cole's painting of Kaaterskill Falls, tradition says for $25 and helped to introduce the young artist to Asher B. Durand, William Cullen Bryant and other literary and art patrons in New York. One of Cole's later apprentices was Frederick Edwin Church.

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

![]()

Picturesque

One is sometimes ashamed of the early depictions of natives as savages, by Europeans, just as some of the earliest renderings of the national scenery is overly sentimental as opposed to real. The picturesque was one of three classifications according to Lauren Rabb curator of the Arizona Museum of Art,

"Pastoral landscapes celebrate the dominion of mankind over nature. The scenes are peaceful, often depicting ripe harvests, lovely gardens, manicured lawns with broad vistas, and fattened livestock. Man has developed and tamed the landscape – it yields the necessities we need to live, as well as beauty and safety. The Picturesque — a category developed in the late 1700s by clergyman and artist William Gilpin — refers to the charm of discovering the landscape in its natural state. Gilpin encouraged his followers to engage in “picturesque travel” – the goal of which was to discover beauty created solely by Nature. The artist and the viewer delight in unspoiled panoramas: sunsets behind majestic mountains, an egret taking off from a quiet marsh, a deer bathed in a shaft of light in the woods. These scenes are uplifting, but not frightening."

Lauren Rabb, Curator

19th Century Landscape - The Pastoral, the Picturesque and the Sublime. October 9, 2009 – March 2, 2010.

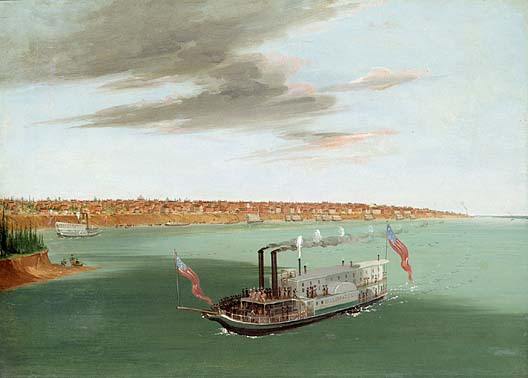

A view of Richmond Virginia in antebellum [before the Civil War] times with the new state capitol on the hill to the right of city.

There is a sentimentality in some vernacular art that American landscape artists attempted to escape, and none more than George Catlin, Frederic Edwin Church, and Martin Johnson Heade.

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

![]()

"to rescue from oblivion their primitive looks and customs." George Catlin.

Earliest among theme, George Catlin in 1827 even painted a bird's eye view of the often painted Niagara Falls. But he is best know for his five trips west just after the Indian Removal Act was passed. Catlin went west in the 1830s also just prior to a seriously devastating cholera epidemic that would alter the very people and their activities that he tried to depict on canvas.

On the great plains in the 1830s: George Catlin.

George Catlin, St. Louis from the River Below, 1832–33. Oil. Smithsonian Institution

Catlin,"Buffalo lancing in the Snow Drift," Oil on canvas on paperboard, 1861-1869.

Catlin, "Commanche horseman." Oil on paperboard, 1861-69.

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

![]()

The Americas' grand sweep: Church.

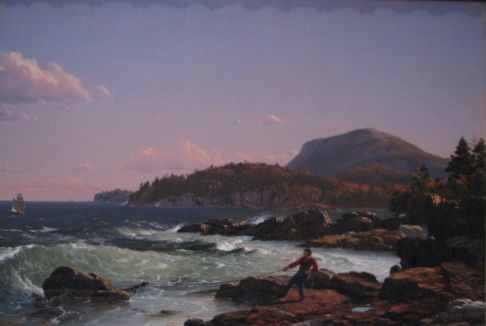

F. E. Church, Newport Mountain, Mount Desert, 1851.

"He was a central figure in the Hudson River School of American landscape painters. While committed to the natural sciences, he was 'always concerned with including a spiritual dimension in his works'."

"By the late 1840s, Church had fallen under the spell of the renowned naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, whose treatises and travelogues based on his five-year (1799–1804) expedition in the New World were widely translated and read. In his culminating work, Cosmos(1845), Humboldt implored artists to travel and paint equatorial South America."

Kevin J. Avery

Department of American Paintings and Sculpture, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

![]()

The smallest & brightest of things for nearly seventy years also caught his attention: Heade.

Heade, Rio de Janeiro Bay, 1864, Oil on Canvas.

A National Gallery of Art exhibit of Heade's work in 2000 suggested that "the painter's key themes of seascapes, salt marshes, still lifes, magnolias, and hummingbirds and flowers of Brazil."

"In later life Heade's wanderings took him to various spots, including British Columbia and California. Never fully accepted by the New York art establishment – he was, for instance, denied membership in the Century Association and was never elected an associate of the National Academy of Design – Heade eventually settled in Saint Augustine, Florida, in 1883."

Heade's biography from the National Gallery

Nonetheless, Heade has been described as "one of America's most original artists."

"Practically unknown in his own day, Heade today is widely recognized as one of the greatest American romantic painters, and is unique in having been equally able as a landscape painter and as a master of the floral still life. . . . aspects of Heade's work, [include] from his tranquil marsh scenes and dramatic seascapes from New England, to his lush images of orchids and hummingbirds in South America and vivid depictions of magnolias from Florida."

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

![]()

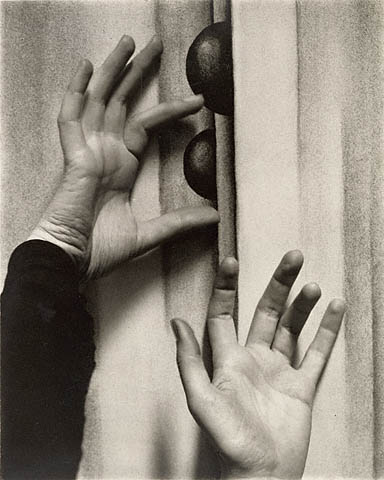

Alfred Stieglitz, was one of the technicians of the camera who desired to make photography into an fine art during the late 19th century. He became the mentor, lover, and spouse of Georgia O'Keeffe who contributed to a redefinition of landscapes in both art and photography in the last century.

Alfred Stieglitz, Two classes of arriving immigrants depicted in photograph entitled,"The Steerage," 1907, Winter on Fifth Avenue, 1893.

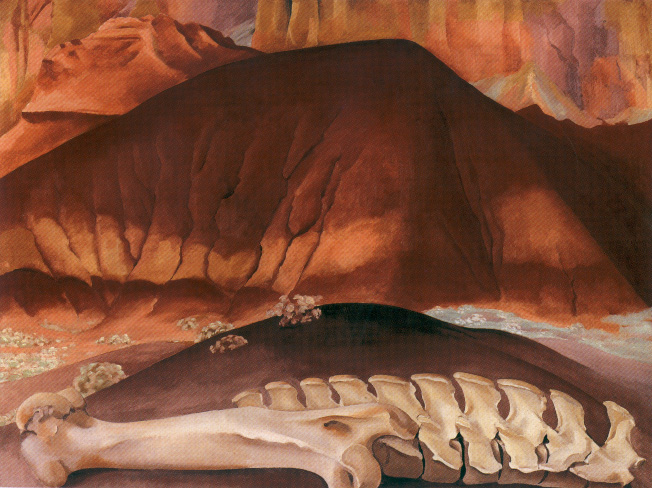

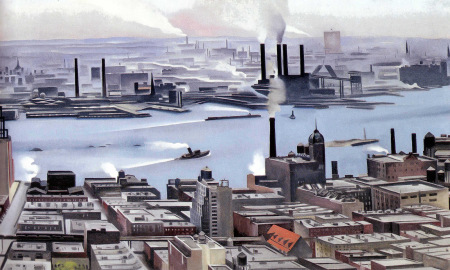

Georgia O'Keeffe, the long time companion of Alfred Stieglitz, was educated in the Texas Panhandle where she developed and unmistakable sense of the natural objects in the landscape and how – by abstracting them – the painter can make a universal statement concerning by what means, where, and why we have come to live as we do.

Having moved from Texas, to New York City and then to New Mexico after her initial early visit there in 1929, O'Keeffe began to paint New Mexico's enormous mountains and rather expansive features when compared to even upstate New York at Lake George. Then in and around the region where she eventually lived out her life at Ghost Ranch, she transformed the land's features, plants, and structures into symbolic expressions of the nearly eternal features that speak to the entwining fabric of the terrain.

Georgia O'Keeffe, Red Hills and Bones, 1941: Oil on Canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art

In her works we see the landscape's features as so much more than mere excrescences of the planet, or symbols of human frailty. Instead in her landscape paintings landscapes become a necessary partner because these facets of the terrain play fundamental roles in the human psychic balancing act between the abyss and despair of experience or emerge as landmarks in a geography of hope. It was this very geography of hope, as Wallace Stegner called the nation's settling of the arid west, that is portrayed so artfully in the works of Georgia O'keeffe.

Georgia O'keeffe, On the River, 1964; Oil on Canvas, New Mexico Museum of Art.

Above in the painting also named: "From the River Light Blue" here we can see a shift in perspective in O'keeffe's paintings. "O'Keeffe's perspective on the world changed after her first time in an airplane in the 1950s, and its repercussions could be felt in her subsequent paintings, both in the subjects she chose and the sizes of her canvases," as Lisa Messinger of the Metropolitan Museum of Art writes.

During O'Keeffe's career she modeled for and later married Alfred Stieglitz, an New York gallery owner and advocate of the German avant-garde in American Art in the early twentieth century.

"The East River From the 30th Story of the Shelton Hotel," 1928

Georgia O'Keeffe's hands photographed by Alfred Stieglitz.

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

![]()

An abstract expressionist, Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) in her work reveals the modern sensibility of painters inspired by a sensitivity to landscape, but not bound by it in the sense that Frederick Church so carefully depicts the nuances of light, color, and texture as it informs the immediate and distant geographical features of the contoured land he painted. As the New York Times reporter Grace Guelck said of Frankenthaler's means,

"Ms. Frankenthaler more or less stumbled on her stain technique, she said, first using it in creating “Mountains and Sea” (1952). Produced on her return to New York from a trip to Nova Scotia, the painting is a light-struck, diaphanous evocation of hills, rocks and water. Its delicate balance of drawing and painting, fresh washes of color (predominantly blues and pinks) and breakthrough technique have made it one of her best-known works."

Helen Frankenthaler (American, 1928-2011). Mountains and Sea, 1952. Oil and charcoal on canvas.

Helen Frankenthaler's "Nature Abhors a Vacuum," 1973. [ Patrons' Permanent Fund and Gift of Audrey and David Mirvish, Toronto, Canada .] National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Contemporary art fails to inform us sufficiently of our biases

This behavior of idealizing the setting can confuse the history we write, unless you recall that perception always –to some greater or lesser degree– involves illusions.

Under the spell of these artists anyone is likely to consider one's nation as a nude model forever posing to the voyeuristic appetites in all of us. But the landscape poses and particularly so for the artist and the fine art photographer, such as here as it posed for Minor White.

White's photograph of these two barns depicts how the dark and light pair intrude upon the nearly flat landscape rising up from the plains as if to accentuate the fact that the agricultural revolution protrudes up into our very lives, through everything we eat, if not everyplace and structure we see upon the land. But here also is the stretched shadow across the land of the utility pole for electric wires. No longer isolated on this mowed prairie, the two barns are now tied to the grid of pulsing electrons that knit contemporary American society together in ways that were never imagined when the telegraph first chased the transcontinental railroad tracks from Chicago to San Francisco in 1869. The country seems poised like some wretched prostitute to give up its pain along with its pleasures for the intrusive eyes, the dangling wires, the felled forests converted into timbers to hold together these barns and support the electrical cables.

Clearly the landscape is more than just an invention of the artist and the photographer? But in a very real sense, in the sense that we invite ourselves to "take its picture," or "paint its profile," the land and its structures both natural and crafted is converted into our supine subject when we photograph a view point, or paint some vista. And in that sense art is the twin of development in that we subject the land and its inhabitants to our desires to portray "as we like it," and not necessarily as it is. By "as it is" one could easily argue that the terrain is not as much an obstacle as it is an active participant -- hot, oozing with not so pretty things and heaving under the sometimes violently expressed pressures seething below the surface. Until we realize that we are spellbound by "naked nature," and at the same time seduced into having our imaginative way with the terrain's water, trees, topography and all or some of its local inhabitants, we will not realize that even a passive intrusion is an imposition of the human will on something that is never willing to submit to our fantasies, let alone passively endure development without unforeseen consequences.

Truly, as Robert Frost suggested "the land was ours, before we were the lands." And in the very real sense that the geology and biology of this place must enter into and impregnate our imaginations, we will always remain mere voyeurs, waiting our turn for some sweaty, heaving, and sloppy chance to make the land ours without ever being willing to give it the freedom it has so continuously and blithely bequeathed to us.

JVS, August 9, 2007, revised 2014.

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

![]()

Truisms

Art is an imitation of nature.

Charles Fraser's 1802 View of Charleston, South Carolina's environs.

Landscape art is representations of natural settings, with and without people in the frame of view.

le long duree

The notion of long-term [le long duree in the terms of Fernand Braudel] is the opposite of short-term.

But these mean very divergent extents of time and durations to different people. Art from centuries past, just like old maps, can be used to inform the varied meanings we attribute to long ago as opposed to recent past.

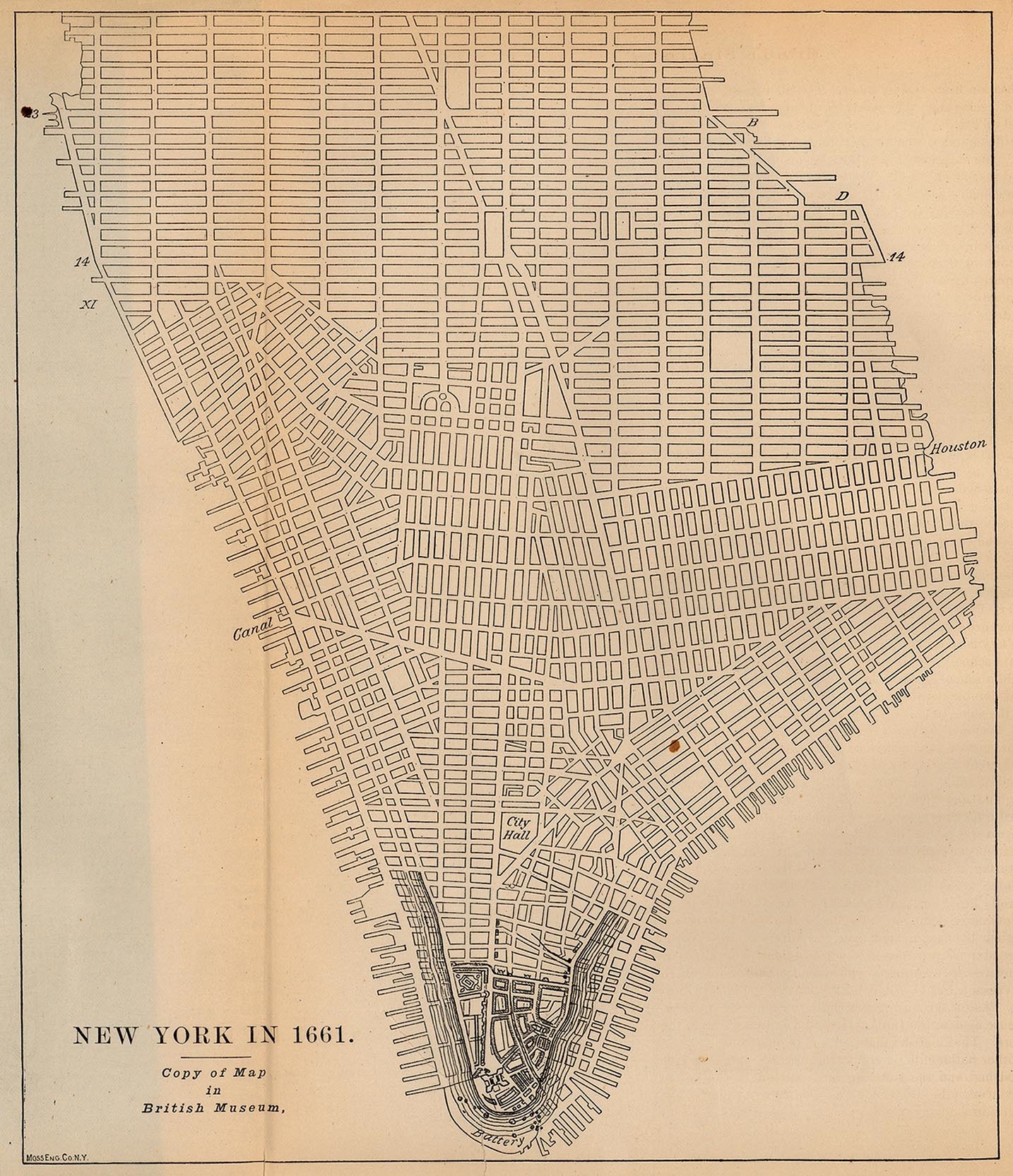

Seventeenth Century Eighteenth Century Manhattan when the British acquired it lower.

New York & Brooklyn in 1776.

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

Irrationality in depicting scenery is inherently expressive of post-war art.

Adequate knowledge is always restricted by access, talent, and viewpoint, or perspective (point of view), yet it is even further circumscribed by physical and biological conditions.

Art makes it possible to see in sharp relief important themes, but can also mask the reality of those "objects" – the objective things seen – as subjects of a painting, sculpture or other creative expression.

Symbolizing noble and ignoble achievements a painting David cutting the head off of the slain Goliath is set beside Rodin's sculpture: "Bronze Age."

New York Times

" Helen Frankenthaler, Abstract Painter Who Shaped a Movement, Dies at 83," " By GRACE GLUECK, Published: December 27, 2011. Nature Abhors a Vacuum

the artists | the problem | the sensibility | diversity | photography | expressionism | some lessons

![]() Terry T. Williams | Gerald Durrell | D. H. Lawrence | Arnold Pacey | Tim Radford | Norris Hundley | Mary Austin | John Wesley Powell | Wallace Stegner | Siry, Marshes

Terry T. Williams | Gerald Durrell | D. H. Lawrence | Arnold Pacey | Tim Radford | Norris Hundley | Mary Austin | John Wesley Powell | Wallace Stegner | Siry, Marshes

.gif)

. A View Near Charleston, South Carolina. The Carolina Art Association, Charleston, South Carolina..jpg)