Essay

Essay Navigating the site:

Environmental Conservation embodies an Ecological Value

by Joseph V. Siry

Conservation is the measure of the distance between our intentions and our abilities to thoughtfully behave in ways that secure more than just our narrow needs to live well. Without conservation of natural resources a nation of over 310 million demanding people is not capable of sustaining the nation's needs for water, electricity, timber, recreational lands, fisheries, and other natural resources. While Americans represent four percent of the world population we consume one-fourth (25%) of the Earth's resources. To sustain the United States' level of consumption and exploitation patterns we would need three more Earth-sized planets.

Conservation meets preservation

In 1903, President Roosevelt met John Muir on a three day camping trip in Yosemite National Park. Of it Roosevelt later wrote: "we lay down in the darkening aisles of the great Sequoia grove. The majestic trunks, beautiful in color and in symmetry, rose round us like the pillars of a mightier cathedral than ever was conceived even by the fervor of the Middle Ages." [An Autobiography, 1913].

President Theodore Roosevelt's 1908 speech, "Conservation as a National Duty," Washington, D.C.

The numerous varieties of approaches we have to protecting natural resources from harm loss or decay have emerged due to historical conflicts. These serious disagreements or schisms over the means to effectively protecting water, fisheries, minerals and wildlife emerged to alter American political and social patterns due largely to the growth of population, urbanization and industrialization in the last half of the nineteenth century.

Every society faces the tasks of adjusting to new conditions brought about by changes in climate, demographics, disease or technological designs. In ancient India, medieval England and modern Europe conservation impulses were translated into ruling policy as leaders recognized the necessity of keeping vital resources from damage, degradation, destruction or decay. When in the late nineteenth century American writers, scientists, artists and politicians recognized that the country's rivers, forests, fisheries and wildlife were vulnerable, significant reform proposals that embodied conservation were proffered. Between 1872 and 1916 federal agencies were created to protect places where scenic quality, fisheries, timber, birds, wildlife and parks were threatened by a lack of enforceable remedies to enhance the natural features inherent in landscape. The Forest Reserve Act in 1893 was proposed in order to protect land for lumber use and watershed protection because poor logging practices caused erosion, a rapid loss of water, and a waste of valuable wood.

Important dates that are indices of the growth in conservation policies:

1864 Lincoln gives Yosemite Valley & Sequoia's to California to protect

1871 U. S. Fish Commission established to restore fisheries

1872 Yellowstone set aside by Congress as a "people's park" for "all time"

1881 The Division of Forestry created

1885 New York State creates the Adirondack Forest Preserve

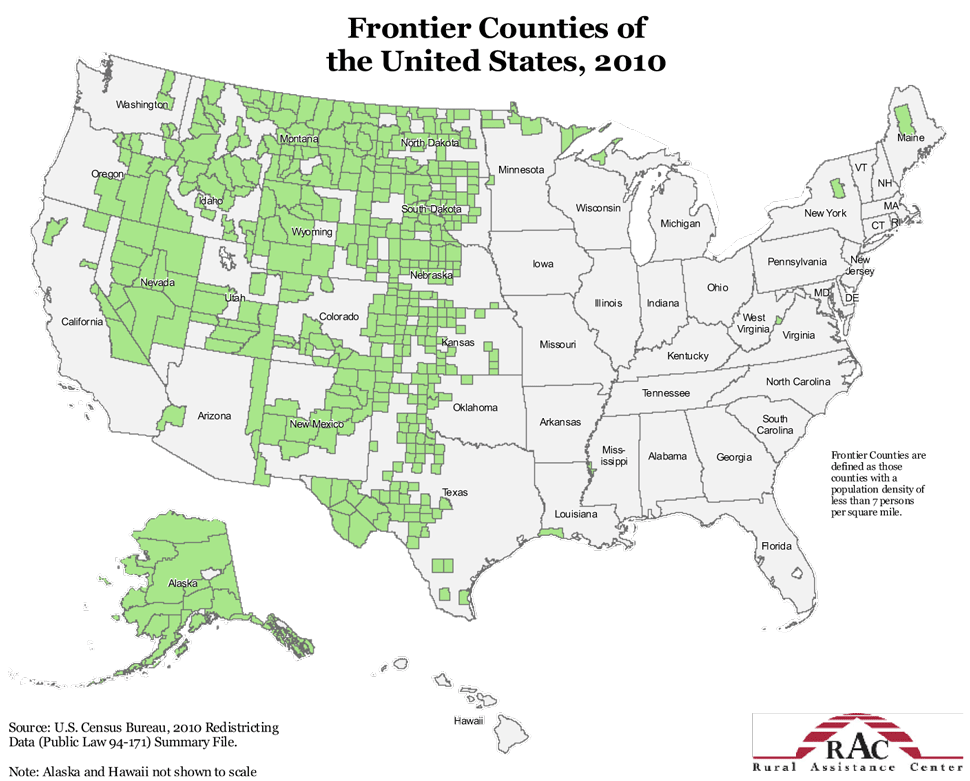

1890, the closing of the frontier – as a contiguous line of settlement west of the Mississippi River.

1893 Forest Reserve Act passed to set aside timberlands in the public domain

1897 Forest Management Act defines the purpose of timber reserves

1900 Lacey Act for the protection of wildlife enacted

1902 Bureau of Reclamation created to irrigate and drain public lands

1906 Antiquities Act, passed to protect archaeological and historical resources

1908 White House Governor's Conference on Conservation sponsored by Theodore Roosevelt.

1913 the Raker Act lead to the creation of Hetch Hetchy reservoir in Yosemite National Park

1916 The creation of the National Park Service (NPS) to protect rare scenic places

***

Census of population

| population | % urban | technological changes | |

| 1790 See the actual census here |

3.90 million |

5% |

cotton gin, steam engine |

| 1860 |

31.43 million |

20% |

Civil War, oil, steel, & coal |

|

1870 |

39.81 million |

25% |

railroads, tall buildings, telephones |

|

1880 |

50.15 million |

28% |

hydroelectric plants, steam turbines |

|

1890 |

62.94 million |

35% |

radio, radioactivity, cars, punch cards |

|

1900 |

75.99 million |

40% |

steel bits, Haber–Bosch fertilizer process, airplanes |

|

1910 |

91.97 million |

45% |

assembly lines, pollution warnings |

|

1920 |

105.71 million |

51% |

national highways, tissue paper |

| 1990 |

277.89 million |

79% |

automation & digital revolution |

| 2000 | 281.41 million | 80.7% | census.gov/prod/cen2010-2000 |

| 2010 | 308.71 million | http://www.census.gov/2010census/ | |

| 2015 estimate | 320.38 million | Cloning, health care, wireless telecoms |

The growth of urban population in this 21st century has outpaced the national average rate of population increase. What do these figures actually mean?

A brief look at the above tables will reveal the emergence of conservation simultaneously with persistently increasing changes in the number of people, the types of technology and the percentage of urban residents. While any sixty year period reveals similar changes in population, technology and affluence as those referred to above, the formative period in the creation of our national forests, monuments parks and wildlife refuges was accompanied by revolutionary changes from industrial production to the construction of vastly larger cities. These industrial and municipal changes required an increase in the consumption of raw materials in the form of water, energy, minerals and landscape that contaminated the land, air, and water beyond the existing capacity of institutions to assure public health and safety. Conservation reforms were seen by many advocates as a partner in the development of the nation's industrial and commercial wealth. As urban needs replaced agrarian patterns of land-use mechanized agriculture demanded irrigation and drainage to meet the growing demands.

The earliest schisms in the movement to protect natural resources from wanton destruction due to mining, logging and reclamation emerged from this clash between agrarian traditionalists and urban reformers. In the case of Los Angeles' need for a municipal water supply, an urban aqueduct replaced the original agricultural reclamation of the Owen's Valley in the Eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains. Just as demand for water and power in San Francisco caused a clash over the use of Yosemite National Park's water, the Owen's Valley struggle divided preservationists from conservationists. While both groups shared a deep concern for the protection of natural landscapes the means by which the two factions viewed nature and thus sought to defend values inherent in rivers, forests and wildlife differed.

"Faces of Rural Poverty," Alabama Farm family in 1938, James Agee.

Our current redefinition of conservation in the light of new technological and demographic impacts on our global environment owes its underlying unity to George Perkins Marsh's ideas of "geographical regeneration;" to "restore the disturbed harmonies" he had imagined were manifest in the pristine natural conditions of places. Pinchot and Muir led factions of Marsh's followers in allegedly different directions to protect nature. But they deepened our understanding of the essential balance between the need for nature in defining our cultural identity and the necessity of using natural resources to meet rising future demands for goods and services.

The rift between those who sought to stop development of resources on reserved terrain or scenic landscapes and those who pursued the sustained use of these same sources of economic wealth centered on the personalities of preservationist John Muir and conservationist Gifford Pinchot. Concerned for the scenic beauty, natural history and cultural importance of landscape Muir and others hoped to protect national parks from exploitation of wildlife, water, or timber within the boundaries of the protected areas. Pinchot, however, as a trained forester had restored the gutted lands in North Carolina the Vanderbilt family had acquired as the Biltmore estate (Photographed in the picture below).

He, unlike Muir, Pinchot was convinced of the compatibility of sustained yield forestry and scenic enjoyment of accessible resources. Although the fight over Hetch Hetchy and the Owen's valley watersheds was bitterly divisive the national movement for the protection of nature gained adherents to the cause of reform over twenty years of arguments.

Pinchot turned this once eroded and "gullied-out" –– meaning seriously eroded –– tobacco plantation into a resilient forest.

It is easy to characterize the differences between Muir and Pinchot with respect to rivers, forests and wildlife. Muir viewed these features as essential sub-units of a functionally healthy landscape based on the quality and quantity of the fish in streams, the size and age of the trees, and the number and variety of the deer, panthers, bears and birds. Pinchot, while recognizing these biotic pieces of the landscape's integrity argued that conservation could not win broad support unless economic considerations were of paramount importance. Where Muir saw fish, Pinchot recognized the cubic feet of stream flow necessary to irrigate cities or farms. Unlike Muir, Pinchot saw forests with respect to the board feet of timber available per acre on a sustained yield basis. Where Muir argued for wildlife protection, Pinchot recognized the necessity of hunters to pay the cost of conserving wildlife refuges. While this split persists in environmental debates today the broader consensus established a national level of funding and research for the long-term management and protection of natural resources. The national protection of our natural heritage by applying science to the renewal of landscape is one product of these early conflicts in the formative period of the conservation movement.

The precise circumstances that brought conservation to the national level of political reform have changed. America for example has only 4% of its land sequestered as wilderness and half of that is in Alaska. Two hundred million more people dwell in and demand thirty times the amount of resources per person as did the 1900 generation of Americans. To maintain our current affluent standards of living each American, for example, uses the equivalent of 10 acres of land each year! Despite these changes such a direct impact has generated problems only hinted at 100 years ago. With 4.5% of the world's population, the United States consumes over 30% of its resources producing more carbon dioxide waste per person than any other country on earth. Pollution, habitat loss, decline in species numbers and variety, and shortages in certain vital industrial materials has transformed these common conflicts over conservation from mere regional skirmishes into international negotiations over the future of forests, climate change, population planning and biological diversity.

This changing conflict over use and reservation of resources is the result of demographic and technological forces that have demonstrated the links between economics and ecology that once troubled wildlife biologist Aldo Leopold. He conceived of ecology as a round river whereby the movement of moisture from land to air and into water is a metaphor standing for how rivers, forests, wildlife and humans all shared the same sources of well-being. The health of the ecosystem he believed was embedded in the beauty and functional integrity of places. These sources of biotic wealth must be restored in order for humankind to advance morally as well as economically. Like any circular relationship, Round River, represents the facts that whatever we do to the surroundings we inhabit, we ultimately do to one another.

When in the following two decades, environmental conservation was redefined by Raymond Dasmann he showed that this new biologically centered approach to protecting natural and cultural resources embodies an inherent ecological value because the functional connections among water, air, soil, fisheries and wildlife must become the foundation of protecting people and the planet simultaneously. When debating whether caribou herds or oil drilling is a more wise use of natural resources in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the image of Round River reminds us of a deeper reality. When protecting salmon on the Columbia rive and the old growth forests of the Cascade mountain watershed that same imagery reminds us that these salmon, forests, and water are locked together tightly in a never ending, revolving fund of life where one ingredient nourishes and is sustained by each and all of the other ingredients in this puzzle of the landscape. That is one meaning of ecological value. The coal, gas, and oil we burn today create warmer climates, more acid rain and increasingly acidified oceans tomorrow.

Unprecedented threats have plagued past generations. By the 18th century some people realized population growth had outstripped the capacity of the land to sustain human food needs, by the 19th century sensitive observers, people like Marsh, Olmsted, and Powell recognized that human land-use had polluted and diverted the essential waters people needed to sustain their agricultural and manufacturing demands. In the 20th century it became obvious to engineers, scientists and writers that human consumption had altered the very atmosphere that life and civilizations had always depended upon to nourish, shelter and maintain people's health. Despite our debates over how best to apportion our dwindling supplies of water, arable land, forests, and natural resources, we all live downstream on the same river of life.

+ 2000 words.

Science Index | Site Analysis | Population Index | Global Warming Index | Nature Index