What is a treasure?

Bronze the alloy of copper and tin

|

Aslihan Yener, Assistant Professor in the Oriental Institute, believes a mine and an ancient mining village she found in the Central Taurus Mountains in Turkey demonstrate that tin mining was a well-developed industry in that area as long ago as 2870 B.C., at the dawn of the Bronze Age. |

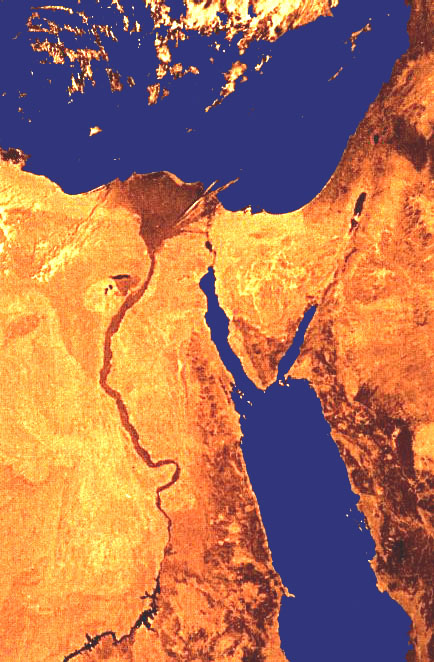

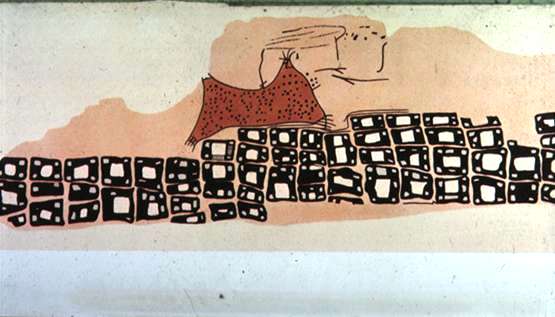

| A map from Anatolia, the earliest ever found. |

|

|

The site of the mine, Kestel, is about 60 miles north of Tarsus. Yener's work at the mine and at nearby Goltepe, an ancient miners' village, provides new insights into the development of the tin industry. Perhaps most important is her discovery that tin can be smelted in crucibles at relatively low temperatures, a finding that may change established theories about economic and metallurgical developments in the Bronze Age Mediterranean world. The Bronze Age, which began about 3000 B.C., was a time of great economic expansion throughout the Middle East. During this time, great city-states such as Troy rose in Anatolia (modern Turkey) and empires developed in Mesopotamia. "Tin's economic role in the metal technology of the time is perhaps akin to that of oil in industry today. It was the most important additive to the then high-tech metal of its age -- bronze," Yener said. Bronze is an alloy made by combining copper with as much as 5 to 10 percent tin. Because it is more easily cast in molds and harder than copper, bronze replaced copper in the production of tools, weapons and ornamental objects. The Bronze Age lasted until 1100 B.C., when iron became the most important metal in manufacturing. Despite the importance of bronze and the role tin played in its production, scholars have long believed that tin was not readily available in the Middle East. Later cuneiform texts on clay tablets speak of sources to the distant east, and researchers have believed that perhaps Afghanistan was the only likely location of tin mines. Yener's discovery shows that tin came from local as well as imported sources. University of Chicago: Chronicle. Jan. 6, 1994, Vol. 13, No. 9. |

|

A number of significant innovations took place in fire, stone working, domestication of plants, animals and metal alloying techniques; after the ice age in Asia Minor, in what is today Georgia Armenia, Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, such that the subsequent civilizations gave birth to the cultures of the fertile crescent. Often the copper smelting rooms were adjacent to temple complexes.

Siry, 2007.

Eberhart Chapters

- Atoms, Marbles, and Fracture

- Ancient Art, Ancient Craft

- Ancient Science

- Embrittlement and other coincidences

- Shocking Simply Shocking

- Things that Don't Break

- When the Going Gets Tough

- Only the Tough Get to Go

- Why ask Why?

- Right Answers, Wrong Answers, and Useless Answers

- Inside Materials by Design

- Materials by Design Resureection

- It's Broke We/ve Got to Fix It

Tools of Toil: what to read. Tools are historical building blocks of technology.

Authors:

Pursell | Pacey–World | Postman | Head | Tenner |Pacey–meaning| Eberhart | Snow | Kaku | Boulding | Delillo | Kranzberg

| Postman–Tech | Postman–Television |

This page was created, by J. Siry

.gif)