Navigating the site:

A Sensitivity to Places: Regeneration, Organisms,Technology and Environments. (2014).

Joseph Vincent Siry

"We live in a daily marketplace of electrons, with trades measured in millionths of seconds."

p. 27. Neil Shubin, The Universe Within: The Deep History of the Human Body, 2013.

"The twilight of the beginning of our history was the nightfall of some previous history, which will never be written."

p. 51. D. H. Lawrence, Etruscan Places, London: Martin Secker, 1932.

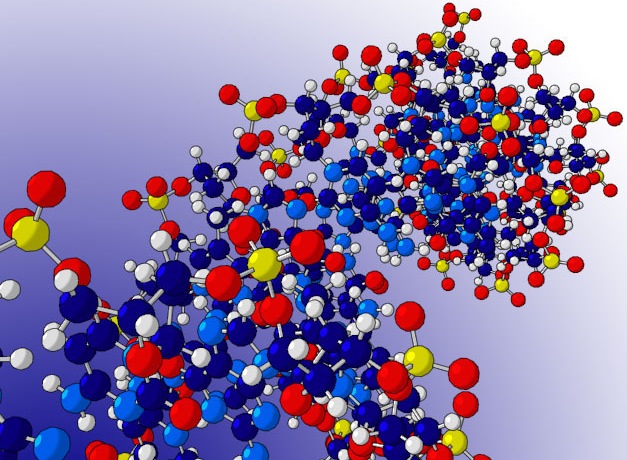

The disclosure of "the complexity of the land organism" Aldo Leopold insisted was "the outstanding scientific discovery of the twentieth century" just before DNA's structure was unraveled in 1953. This deliberate contrast between the functionality of land and the form of the double helix is a conscious effort to overdraw a distinct contrast between environment and inheritance in order to point out and resolve by analogy several obstacles that dull our sensibilities when understanding the character of places. Worse, these impediments can generate pernicious myths about places. Because ambivalent sentiments arise from human experience of geography these perverse dichotomies allow us to distinguish one place from all other places, but generate disagreement about systematically articulating the qualities of value in any place. We distinctly separate terrains as to how well they do or do not exhibit identifiable features of scale and functions that contribute to a sense of place. Such ambivalence about the qualities of place creates lingering problems. To see the values in any land as terrain – as opposed to land as an organism – it is necessary to overcome this confusion and move from identifying static attributes to thinking about processes that function to nourish people in healthy places. We must disengage from several dichotomies in order to comprehend how the renewable functions of land sustain life and civilization. Confusion generated by these prevalent dichotomies can blind observers to the contingency inherent in biogeographical processes. A change to understanding processes is an initial step in knowing how thoroughly technology is entwined in sustaining cultural landscapes. By looking at ten artists who portray the contingent layers of places and twenty authors who define geographical scales contributing to the meaning of remnant structures on terrains one can comprehend how tensions arising from these ambivalent attitudes and subsequent dichotomies have prompted disagreement over how well we interpret and convey the meaning of places.

George Inness, Evening Landscape, oil on canvas, 1863. Depicts a farm worker and fields at twilight. Commentary on Inness.

Confusion commonly arises because we are in a field where biology, geography and history meet upon uneasy boundaries. Evolution dictates a fusion of these disciplines when describing an inherent complexity in topography, terrains and settings. But each discipline from geography to biology and architecture treat the places differently. We are now –as in the past– called upon to create a reliable method of accounting for the way intrusions alter these surroundings in which we the public and specialists may or may not perceive that landscapes are fungible.

Ignoring the gulf between the public that invests in real estate and the specialists who describe environmental conditions of places, it is difficult for many to see that technology is intimately related to how we perceive what has been done and what we are doing to geographical settings that may disturb, damage, or alter our definitions of place. The importance of places has urgent need for our study because as they relate to land use and land use changes contributing to abrupt climate change places are where laws of thermodynamics and human action have consequences. To rephrase the first and second laws you could say first, places are where matter and energy are conserved and to which you discard disorder or pollution with consequences because matter cannot be destroyed. Second every place accumulates entropy or disorder at different rates. These two laws reveal how the means by which technology is applied may either enhance or disrupt places. Acid deposition from smokestacks is a clear example of these consequences affecting water, fisheries, forests and wildlife even when the affected places are far distant from the source.

In recognizing how technology both shapes and is shaped by circumstances we may associate identifiable architectural qualities with a sense of place and get beyond a set of blinders I call perverse dichotomies. Some of the problems these "either – or" dichotomies perpetuate include our fondness for special terrains or landscapes over other places within those same countryside or over other allegedly less attractive settings.

Rosa Bonheur, Plowing in Nivernai, oil on canvas, 1850.

There are at least three dissonant dichotomies that we should identify and try to reconcile because the emotions associated with each inhibits our capacity to keep pace with factual data about topographical changes and the re-creation or restoration of cultural landscapes. Specialists have identified three significant opposing arguments that can perversely hamper what we observe and chose to sacrifice or preserve.

- Static landscapes (or architectural) vs. fluid (or automotive) view sheds that have influenced alterations that Jackson has said is the current challenge.

- The nature vs. nurture argument has two related elaborations,

- Plato's second nature that humans impose on "unfinished" original nature to secure some end or purpose.

- "Spacetime" in the sense that Einstein unified the concepts, so Jackson insists a sense of time is intrinsic to defining a place.

- The final dissonant dichotomy with perverse outcomes is the way we distinguish place as a source of ethnic identity vs. technological imperatives to transform places. The dichotomy has led writers like Paul Tillich and Arnold Pacey to warn about the power of these two –not always contrary – influences.

Before the Second World War the popularity of rooting ethnic identity into the particular soil of the landscapes from which a people were believed to have sprung was widespread. In that sense technology is entwined with creating identifiable cultural landscapes. Paul Tillich wrote:

"The power of space is great, and it is always active for creation and destruction. It is the basis of the desire of any group of human beings to have a place of their own, a place which gives them reality, presence, power of living, which feeds them, body and soul. This is the reason for the adoration of the earth and soil, not soil generally but of this special soil, and not of earth generally but of the divine powers connected with this special section of earth . . . . " 4

D. H. Lawrence and Lawrence George Durrell are just two of the many writers, who before the genetic revolution sought to define the evocative, original, and cultural environments in which past and current civilizations found some sense of belonging and identity or even a sacred trust to ensure their survival.

Perverse use of these dichotomies to obscure facts also allows us to better comprehend how a sensibility for natural places could displace people. Simon Schama has shown both the roots of this romantic allure and preference for particular landscapes as leading to diabolical consequences of the Third Reich in preserving Bialowieza Forest in Poland as a special hunting preserve because the forest biome was considered sacred. This preference for place persisted despite its residents who also possessed sensitivity for place were nonetheless destroyed by Hermann Goring in the process of protecting the trees and the rare animals. Schama writes "Between June and mid-August 1941 thousands of farmers and foresters from the old timbered villages on the edge of the forest were deported out of the area . . . . At least nine hundred villagers were murdered . . ."

Since that war our fondness for removing settlers from certain landscapes has been reduced but this has not necessarily diminished our desire to protect terrains that have peculiar appeal for the larger mass of people. Alan Gussow wrote that "We are homesick for places, we are reminded of places, it is the sounds and smells and sights of places which haunt us and against which we often measure our present."

Places are geologically and climatically evolving vegetative conditions in which particular associations of animals reside in and populate terrains that may be converted into landscapes with identifiable stratigraphic, ecological, and cultural layers. Aldo Leopold, "Round River" in A Sand County Almanac, 1949. Sierra-Ballantine ed. (New York: Ballantine Books, 1970). p. 190. Neil Shubin, The Universe Within: The Deep History of the Human Body, 2013. p. 27.

D. H. Lawrence, Etruscan Places, London: Martin Secker, 1932. p. 51.

James Watson, The Double Helix. (New York: Penguin, 1968). pp. 124-136.Painting #1) George Inness, Evening Landscape, oil on canvas, 1863. Depicts a farm worker and fields at twilight.

Physical properties of a place, from the Greek concept of oikios topos, or Theophrastus, are best recognized by plants, or associated vegetation; hence plant communities indicate ecological situations that define the biophysical situation of places.

Painting #2) Rosa Bonheur, Plowing in Nivernai, oil on canvas, 1850.

John Trumbull, View on the West Mountain Near Hartford. oil on canvas, 1781.

A) A Distinct Contrast

Between "the complexity of the land organism" Aldo Leopold insisted was "the outstanding scientific discovery of the twentieth century" & DNA's structure that was unraveled in 1953.

This deliberate contrast between the functionality of land and the form of the double helix is a conscious effort to overdraw a distinct contrast between environment and inheritance

1) generates disagreement about clearly articulating the qualities of value in any place. We distinctly separate terrains as to how well they do or do not exhibit a sense of place. The ambivalence about the qualities of place creates lingering problems.

2) To see the values in any land as terrain – as opposed to land as an organism – it is necessary to overcome this confusion. We must disengage from these dichotomies in order to comprehend how the renewability of land sustains life and civilization.

3) Confusion generated by these perverse dichotomies can blind observers to the complexity inherent in how thoroughly technology is entwined in sustaining cultural landscapes. By looking at ten artists and fifteen to twenty authors we can comprehend how the tension created by these ambivalent attitudes has caused disagreement of how well we articulate the meaning of place.

B) Landscapes are fungible

We are now –as in the past– called upon to create a reliable method of accounting for the way intrusions alter these surroundings in which we the public and specialists may or may not perceive landscapes as fungible.

C) Technology is integral to making and sustaining cultural landscapes.

Ignoring the gulf between the public that invests in real estate and the specialists who describe environmental conditions of places it is difficult for many to see that technology is intimately related to how we perceive what has been done and what we are doing to geographical settings that may disturb, damage or alter our definitions of place.

D) We don't see the contingent processes that are constantly altering terrains.

E) The dynamic processes that reshape terrains are capable of nourishing fertility and may be tapped as partners in our choice to either disrupt or promote geographical regeneration to restore as opposed to exhaust our lands' capacity for renewal.

Specialists have identified three significant opposing arguments that hamper what we observe.

- Static (architecture) vs. fluid (automotive) landscapes, Jackson

- Nature vs nurture

- Plato's second nature humans impose on "unfinished" original nature.

- Spacetime in the sense that Einstein unified the concepts. Jackson

- Ethnic identity vs. technological imperatives Tillich

.

The poet Richard Wilbur has suggested,

The artists's rendering of the how rural people utilize a marsh: Washerwomen, or The Marsh, Constant Troyon, oil on canvas, 1840. Art Institute of Chicago.

"a place being a fusion of human and natural order, and a peculiar window on the whole."

Places are geologically and climatically evolving vegetative conditions in which particular associations of animals reside in and populate terrains that may be converted into landscapes with identifiable stratigraphic, ecological, and cultural layers.

The importance of defining place has mostly drawn critical

"The problem is not whether man will or will not alter natural systems, but only how he will do it. . . . Practically all aspects of life are artificial in the sense that they depend on profound modifications of the natural order of things. The life of the peasant is as artificial as that of the city dweller. . . . The reason we are now desecrating nature is not because we use it to our ends, but because we commonly manipulate it without respect for the spirit of place."

Rene Dubos, A God Within, 1984.

But in addition to this tension between good uses and bad means of preserving a place that some authority believes possesses a "sense of place," there is another troublesome dichotomy. This unresolved separation arises when we try to define what precisely a sense of place entails. This tension relates to the deeper argument often called "nature versus nurture." But the anxiety is accentuated by the way in which techniques and tools are used to transform space and the pace by which the familiar landscape is altered. By misunderstanding technology – a word with as many different connotations as nature – there s a tendency to associate a sense of place with enduring areas less altered by human occupation, disturbance, or design. Contrast then is as critical in defining place as is the context that we are a territorial species with Pleistocene honed habits of vision superseding other senses of our surroundings.

Technology as tool-use arose in specific places and altered those conditions particularly after pastoralism, agriculture and mechanization each in its particular manner had become widespread. Remember that the industrial antecedents of electronically sophisticated machines arose in rural conditions close to the resources needed that were at hand in places such as Shropshire, or along the Atlantic Fall line, or in Salzburg. Peculiar places give rise to technologies that are capable of eventually transforming even distant landscapes and those isolated places in ways that only trained observers may be able to discern.

"The iron mines, furnaces, and forges are gone. So in fact this sense of permanence, this feeling of enduring history, is a tease: landscapes alter. Humans make their mark and then in a generation or two the marks are erased: the evidence of what has once been may be visible enough to archaeologists, ecologists, and topographers , to trained eyes but to most of us the countryside we see is timeless: because it is there, and because it looks just so . . . we find it easy to believe it has always looked so."

Tim Radford, The Address Book. (2011). pp. 51-52.

The cultural geographer John B. Jackson's showed that there are numerous technological ingredients that complicate a simple recipe for creating or identifying the taste we have for "a sense of place." He suggests that this picture of architectural transformations as the "secret" behind our ideas of place is being replaced, and a sense of place inherent to all life has been lost in the automotively-influenced landscapes we now inhabit. He warns that the inheritance of architecture that so enthralled writers like Lawrence and Durrell is static and has thus been swept away by the fluid patterns that have emerged and are still emergent with the widespread popularity of automobiles, highways, airlines, and aerospace.

Technology has played an ambivalent and often obscurant role in defining those qualities of places that have meaning for inhabitants and thus the level of technical ability is a significant influence on any shared sense of place. Often the nature versus nurture argument also obscures a reality contributing to a sense of place because arguing over inherited influences versus environmental conditions keeps us from comprehending how places either embody or fail to thrive in possessing qualities we can articulate as culturally significant.

Authorities say:

"The countryside tends to be seen as humans wish it to be. Anthropocentrics all, we see the landscape from our point of view, and even the entity we call the beauty of the wilderness is simply a happy arrangement of high ground and valley, glacier and river, forest and sky, that fits the unconscious frame of reference that we have for beauty: nature builds the structures, but we provide the composition."

Tim Radford, The Address Book, p. 52.

Jackson had argued, "It is my own belief that a sense of place is something that we ourselves create in the course of time." He associates this sense of place with a feeling of homey familiarity; "It is the result of habit or custom." By contrast he notes that "others disagree." He explained that "They believe a sense of place comes from our response to features that are already there – either a beautiful natural setting or well-designed architecture."

"Life must be lived amidst that which was made before. Every landscape is an accumulation. The past endures."

Donald Meinig 1979, p.44

Authors

- Lawrence George Durrell, A landmark Gone

- D. H. Lawrence, Etruscan places

- Aldo Leopold, A Taste for Country

- Arnold Pacey

- Clarence Glacken, "three questions concerning the habitable earth and their relationships to it."

- John B. Jackson, A Sense of Place

- Rene Dubos, A God Within, & Man Adapting

- Ian McHarg, Design with Nature

- Tim Radford, The Address Book

- Alan Gussow, A Sense of Place: The Artist and The American Land. (1972).

- Richard Wilbur

- Terry Tempest Williams, "writing imbued with place"

- Richard Lewontin, the third facet of inheritance

- Paul Tillich, space and time

- Spacetime

- Hippocratic Corpus

Plenitude, a condition of fullness; the abundance of creation and that all possible kinds of being can and do exist because the more there is in the world the better that world is.

Sensibilité, sensibility or sensitivity; that is arising from sensory experiences; manifest ability, capacity to respond, the propensity for an organism to respond to stimuli

Students when constructing a sense of place use words, literature, photographs, pictures, maps, painting, sounds, cuisine and describe ethnic varieties of inhabitants.

Minor White, Two Barns and Shadows, 1955. MOMA

"We are homesick for places, we are reminded of places,it is the sounds and smells and sights of places which haunt us and against which we often measure our present."

Gussow, (1972), pp. 27-28.

- John Trumbull –preindustrial land

- John Constable – rural countryside

- Joseph M. Turner – the technological change

- Constant Troyon – human use of landscape features

- George Innes – the spirituality manifest in landscapes

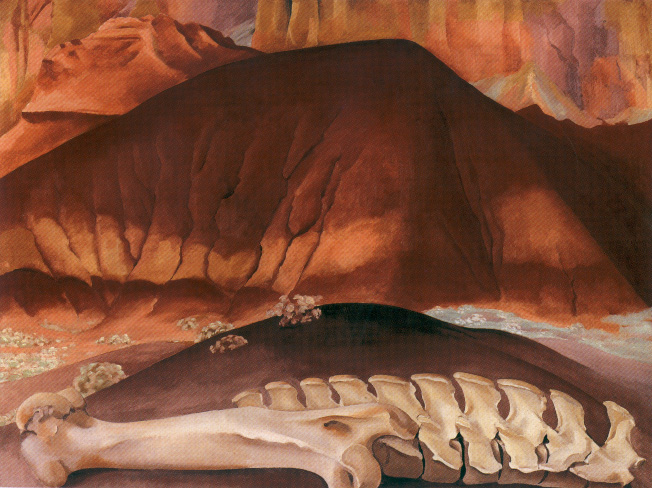

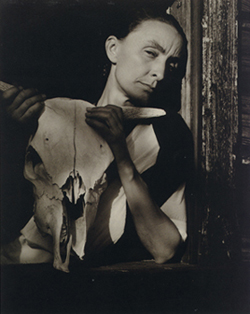

- Georgia O'Keeffe – a sense of place

- Minor White – visually memorable characteristics of places

- Edward Hopper – industrial spaces as formative places

- David Hockney – different vantage points within that same frame in the painting

- Helen Frankenthaler, "Sea Change."

• Glacken's three questions concerning the habitable earth:

- Order and purpose in nature or a designed terrain

- The influence of the conditions of life on humans – plenitude

- Results of the human modification of their surroundings

Clarence Glacken, Traces on the Rhodian Shore. (1967 ). pp. 4-5.

![]()

- Attachment, Arnold Pacey "we can feel strongly drawn to specific places, to to special activities within the landscape, that it is as if nature were indeed 'courting ' us or 'inviting' our participation."

- Peculiarity

- Familiarity

- Necessity

"The price for survival, persistence and evolution was understanding and intelligent intervention."

p. 101, McHarg Design with Nature.

- Invention

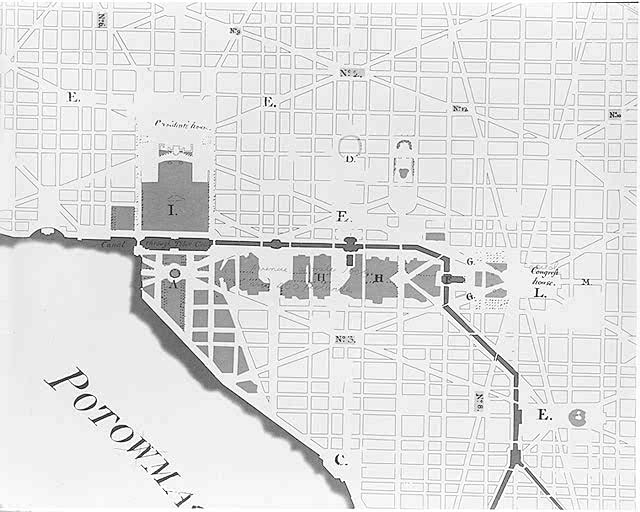

Pierre L'enfant's 18th century design for the new capital with the original waterways.

New York City's lower Manhattan, then and now.

Through this third way called geographical regeneration, George Perkins Marsh suggested in 1864 an idea that could serve as a replacement for the simplicity of dialectical materialism and material culture that lies at the root of our human transformation of the topography of geographical places. In this respect the inherited material, that influences the environments that shape our sentiments in spite of our senses to the contrary must be understood as a spectrum where all elements fuse. The physical, biological and social-psychological attributes of any geography are but pieces of the Gordian knot that is human sensitivity to terrains and the ensuing puzzle of particular places we discern within altered, alterable, and altering topographies. In order to regenerate a landscape that sustains people in society and their civilizations' necessities, we must employ a synthetic understanding of how technology is shaped by physical constraints to alter biological conditions and reshape the sensory acuity of tool users themselves. Cultural landscapes are by definition technically altered geographies in which the expressive arts and techniques of a society are for a time manifest. Such places can reinforce, negate or otherwise affect the behavioral ways in which people respond to changes in their surroundings. In this sense this suggested synthetic approach respects the surroundings as partners enabling the society to recover with the landscape and not in spite of it.

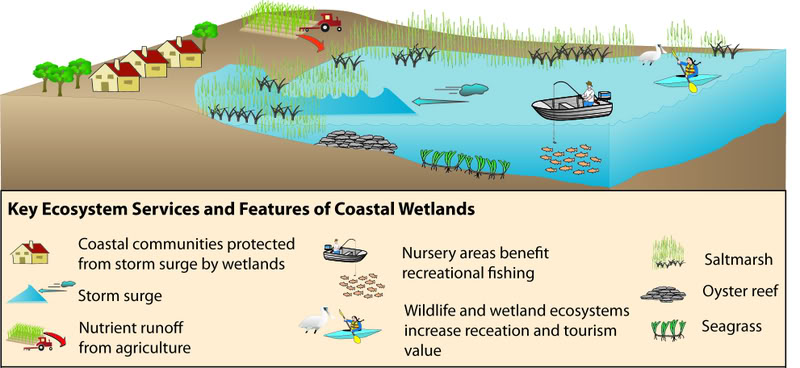

Easier said than done, but natural conditions can often better buffer cultural uses of landscapes than imposing architectural solutions. Wetland, oyster bed, and fishery restoration of Jamaica Bay for example has an advantage of flood protection and a pliable defense against the inevitable rise in seas.

Conclusion

"While we cannot dispense with metaphors in thinking about nature, there is a great risk of confusing the metaphor with the thing of real interest."

"The role of the external environment in this theory is twofold. First, some environmental trigger may be necessary to start the process. Desert plants produce seed that lies dormant in the dry soil until occasional rainfall breaks the dormancy and development of the embryo begins. Second, once the declenchement has occurred, setting the process in motion, some minimal environmental conditions must exist to allow the unfolding of the internally programmed stages, . . . . "

"While we cannot dispense with metaphors in thinking about nature, there is a great risk of confusing the metaphor with the thing of real interest."

"Second, the organism is not specified by its genes, but is a unique outcome of an ontogenetic process that is contingent on the sequence of environments in which it occurs."

"It is useless to call . . . for some more synthetic approach or to say that . . . we need a new insight."

The Triple Helix, p. 109.

By reducing all of the complexity of life into proteins, amino acids, and nucleic acids with different base-pair sequences many hoped that genes possessed the secret of form and function in all living things by the way that proteins alert, silence or in some uncertain way permit inherited information to express or repress traits.

In Achillea plants:

"Such graphs, giving the phenotype (physical properties) of organisms of a particular genotype as a function of the environment, are called norms of reaction. A norm of reaction is the mapping of environment into phenotype that is characteristic of a particular genetic constitution. So a genotype does not specify a unique outcome of development; rather it specifies a norm of reaction, a pattern of different developmental outcomes in different environments."

Progress in biology depends not on revolutionary new conceptualizations, but on the creation of new methodologies that make questions answerable in practice in a world of finite resources.

The Triple Helix, p. 129.

"The organism is determined neither by its genes nor by its environment nor even by the interaction between them, but bears a significant mark of random processes. The organism does not compute itself from the information in its genes nor even from the information in the genes and the sequence of environments. The metaphor of computation is just a trendy form of Descartes's metaphor of the machine. Like any metaphor, it catches some aspect of the truth but leads us astray if we take it too seriously."

Authorities

D. H. Lawrence, Etruscan Places

Aldo Leopold, A Taste for Country

Arnold Pacey, Meaning in Technology

Clarence Glacken, Traces on the Rhodian Shore. Berkeley: US Press, 1967.

"three questions concerning the habitable earth and their relationships to it."

Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory. (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1995).John B. Jackson, A Sense of Place, A Sense of Time -- Spacetime

Rene Dubos, A God Within, Man Adapting, The White Plague

Ian McHarg, Design with Nature

Tim Radford, The Address Book

Alan Gussow, A Sense of Place: The Artist and The American Land. 1972.

Richard Wilbur, "Introduction" A Sense of Place: The Artist and The American Land. 1972.

Richard Lewontin, The Triple Helix, Harvard, 2000. A third facet of inheritance

Paul Tillich, God of space and time

Hippocratic Corpus, in Rene Dubos. Man Adapting. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965.Paul Shepard, Coming Home to the Pleistocene. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1998.

Terry Tempest Williams, An Unspoken Hunger, & Open Space of Democracy

Lawrence George Durrell, "A Landmark Gone," Letters and Essays on Travel. Edited by Alan G. Thomas. (New Haven, Connecticut: Leete's Island Books, 1969).

Henry Williamson, Tales of Moorland and Estuary

Fritjof Capra, The Web of Life

Norris Hundley, The Great Thirst

Mary Austin, Land of Little Rain

Alfred Crosby, The Columbian Exchange, & Germs, Seeds and Animals.

Joseph V. Siry, Marshes of the Ocean ShoreHenry Beston, The Outermost House

Octavio Paz, The Labyrinth of Solitude

Outline of Jackson's argument:

John Brinkerhoff Jackson shortly before his death wrote a long essay arguing how spacetime ought to be the framework to fully embody those qualities that a sense of place indicates about terrains.

- The essay distinguishes between landscape features that engender repetitive monotony and distinctively picturesque qualities of settings.

- He poses two opposite definitions of "a sense of place," but with a caveat about a loss of meaning. [Richard Wilbur argues that words for landscape features are being lost –as well as identifiable landmarks.]

- Jackson defines "a sense of place;" as both:

- "It is by own belief that a sense of place is something that we ourselves create in the course of time."

He associates this sense of place with a feeling of homey familiarity; "It is the result of habit or custom."

By contrast he notes that "others disagree."

- "They believe a sense of place comes from our response to features that are already there – either a beautiful natural setting or well-designed architecture."

a). "They believe that a sense of place comes from being in an unusual composition of spaces and forms -- natural or man-made."

I.) The term is used by architects "injecting life and design into the decaying central city . . ."

p.151.

"The sense of place is reinforced by what might be called a sense of recurring events."

"this expensive facelifting affected the rest of the city very little."

Not the cluster of magnificent forms and spaces; it is the long and empty view," of traffic lights . . . leading to an interstate

"The highway never seems to end"

p. 152.

"Familiarity makes you feel everywhere at home. A sense of time makes you gradually increase your speed."

p. 152-153.

"this all-pervading sameness is by an large the product of the grid –"

"the impact of the grid on a part of the country . . .The High Plains."

p.153.

"where hundreds of thousands of buffalo grazed on the expanse of short grass

The round fields,. . . suggest the same liking for simple geometrical forms, which can be extremely handsome."

Grid "Space rather than land is what the settlers bought"

p. 154.

II.) "Freedom from tradition and freedom from topographical constraints"

p. 154-155.

Reads "less like an account of pioneer farming than of endless land speculation."

"We are fortunate in having an abundance of pictures and plans as well as first hand descriptions of ... western towns."

p. 155.

Main Street was left to decay

p. 156.

"The tradition of the central green or square is a very old one."

"So the dwelling are thinly scattered. "

p. 156.

"people, perhaps the majority, prefer to live at some distance from their neighbors."

III.) "Americans are of two minds as to how we ought to live."

p. 157.

" 'Sense of place' is a much used expression, chiefly by architects but taken over by urban planners and interior decorators. . . , so that it now means very little."

"It is an awkward and ambiguous translation of the Latin term genius loci."

p. 157.

V.) "Our modern culture rejected the notion of a divine or supernatural presence, and in the eighteenth century the Latin phrase was usually translated as 'the genius of place,' meaning its influence."

p. 157-158.

"describe:

the atmosphere to a place,

the quality of its environment.""... we recognize that certain localities have an attraction which gives us a certain indefinable sense of well-being and which we want to return to again and again."

p. 158.

"... they are cherished because they are embedded in the everyday world around us and easily accessible, but at the same time are distinct from that world."

p. 158.

VI.) "... all of these have those qualities I associate with a sense of place:

a lively awareness of the familiar environment,

a ritual repetition,

a sense of fellowship based on a shared experience"

". . . I'm inclined to believe that the average American still associates a sense of place not so much with architecture or a monument or a designed space as with some event, some daily or weekly or seasonal occurrence which we look forward to or remember. . . ."

p. 159.

VII). "That is why we are more and more aware of time, and of the rhythm of the community. It is our sense of time, our sense of ritual, which in the long run creates our sense of place, and of community."

A.) Hidden Rhythm's by Eviatar Zerubavel (1981) "describes as the sociology of time: 'the sociotemporal order which regulates the lives of social entities such as families, professional groups, religious communities complex organizations, or even entire nations.'

B.) "There is no need to dwell on the ever-increasing importance of mechanical time in modern America with our insistence on schedules, programs, timetables, and the automatic recurrence of events – not only in the workplace but in social life and celebrations."

p. 160.

VIII.) " . . . be reminded that this reverence for the clock and the calendar has robbed much social intercourse of its spontaneity and has in fact relegated place and a sense of place to a subordinate position in our lives."

p. 160-161.

A.) On the High Plains for example, he argues that "two factors contributed to an early shift from sense of place to sense of time in the organization of landscape:

1.) "the advent of the railroad with its periodicity. . .

2.). . . second, the almost total absence of topographical landmarks."p. 161.

B.) he insists that Eviatar Zerubavel (1981) argues convincingly that time is the arbiter of contemporary values and "A temporal order that is shared by a social group and is unique to it" must be documented.

p. 161.

C.) That is because ". . . time seems to function a a segmenting principle; it helps segregate the private and the public spheres of life from one another."

IX.) " . . .what we actually share is a sense of time."

Jackson, then without summary, quotes Paul Tillich (extensive excerpt) to conclude that:

"This is the reason for the adoration of earth and soil, not of soil generally but of this special soil, and not of earth generally but of divine powers connected with this special section of earth. . . . "

p. 162.

Life creates the environment, in part:

A taxonomy of three kingdoms of life all share some common genes.

genes make proteins

Mayr | Thomas | Capra | Wilson | Hardin | Darwin | Margulis | Steingraber | Carr | Keller | Watson

Jackson | Glacken | Pacey | Dubos

" 'Sense of place' is a much used expression, chiefly by architects but taken over by urban planners and interior decorators and the promoters of condominiums, so that it now means very little."

"It is an awkward and ambiguous translation of the Latin term genius loci.

He, Glacken equates the idea of plenitude with the concept of biological diversity and the stability of ecological systems. (1967, p. 6.)

Arnold Pacey, Meaning in Technology, 1999 (Boston: MIT Press, 1999) p. 123.

"In today's world, there is perhaps an increased sensitivity to nature among a minority who campaign to protect the environment, who study and enjoy the living things around them, and who celebrate their sense of place."

For the majority in modern consumer society, though, it is easy to feel that the relationships that involve cherishing nature and place have all but disappeared."

p. 121.

"Many people prefer machines that express domination over nature. . . ."

pp. 121-122.

"The word 'courting' here is especially appropriate in expressing a part of the human experience of landscape and nature, for we can feel so strongly drawn to specific places. . . ."

p. 123.

Rene Dubos, Man Adapting

Of Airs Waters and Places

“The oldest known systematic account of the effects the environment exerts on health and on the temperament of people.”

p. 36.

Intended for “primarily providing the Greek physician …with a help to prognosis.”

“continued to dominate western medicine until late in the nineteenth century”

p. 37.

1937

“The Influences of the seasons on infection”

By a Danish microbiologist and epidemiologist

p. 40.

Seasons winds waters sunlight settings soil life

Hippocrates’ checkpoints are:

- The seasons

- Temperament, direction, universality & peculiarity of the prevailing winds

- “properties of the waters” taste, weight “whether they use marshy, soft,” or such as are hard and come from rocky heights, or brackish, and harsh.”

- position in relation to the sun

- “aspect” N-S-E-W exposure

- “The soil too, whether bare and dry, or wooded and watered, or low-lying and hot, or high and cold.”

- “the mode of life of the inhabitants” habits of drink, lunch, & rest; indolent or industrious

p. 37.

“In certain regions where the water is so soft that its calcium and magnesium levels are practically nil, the incidence of cerebrovascular and coronary heart disease is said to be high, even though the amount of fats in the diet are low, and” serum cholesterol levels were low.

p. 40.

Rene Dubos. Man Adapting, (1965). New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965.

Notes from John B. Jackson

"European individuality and the idea of two opposing views of place: his & others.

"The sense of place is reinforced by what might be called a sense of recurring events."

"this expensive facelifting affected the rest of the city very little."

We have altered what place means in the twentieth century:

The street is "Not the cluster of magnificent forms and spaces; it is the long and empty view, of traffic lights . . . leading to an interstate""The highway never seems to end"

152

"Familiarity makes you feel everywhere at home. A sense of time makes you gradually increase your speed."

152-153

"this all-pervading sameness is by an large the product of the grid –"

"the impact of the grid on a part of the country . . .The High Plains."

153"where hundreds of thousands of buffalo grazed on the expanse of short grass.

The round fields,. . . suggest the same liking for simple geometrical forms, which can be extremely handsome."

Grid "Space rather than land is what the settlers bought"

154

"Freedom from tradition and freedom from topographical constraints"

154-155

Reads "less like an account of pioneer farming than of endless land speculation."

155"A flexible and frequently shifting pattern of streets and spaces, adjusted to new real estate values and an increased traffic flow, becomes general: residential quarters, instead of grouping around the business section, tend to move out to where the immediate future is more predictable."

p. 156.

Jackson equates the freedom to move and to use space and says that these values "determined and still determines" much of the planning and architectural design throughout the West."

Jackson, A Sense of Place, A Sense of Time. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994.

Artists

George Inness (1863)

Evening Landscape Washington State University Museum of Art, Pulman Washington. Painting - oil on canvas

|

John Trumbull –preindustrial land

John Constable – rural countryside

Joseph M. Turner – the technological change

Constant Troyon – human use of landscape features

George Inness – the spirituality manifest in landscapes

Georgia O'Keeffe – a sense of place

Minor White – visually memorable characteristics of places

Edward Hopper – industrial spaces as formative places

David Hockney – different vantage points within that same frame in the painting

Helen Frankenthaler, "Sea Change."

Terry T. Williams | Lawrence George Durrell | D. H. Lawrence | Arnold Pacey | Tim Radford | Norris Hundley | Mary Austin | John Wesley Powell | Wallace Stegner | Siry, Marshes