New Places

Paz, Octavio

Spirit of a Place

Artistry | Corfu | deserts | Lawrence Durrell

Volterra, Tuscany: D. H. Lawrence wrote of the antiquities of this inhabited place.

![]()

born: 27 February 1912, Jalunda, India.

Author

of the Alexandria Quartet, and a member of the Bloomsbury group of artists.

Author

of the Alexandria Quartet, and a member of the Bloomsbury group of artists.

Letters and Essays on Travel

Edited by Alan G. Thomas

(New Haven, Connecticut: Leete's Island Books, 1969).

Letter From Lawrence George Durrell; To Lawrence Powell, March 1948, from Argentina

"Across the blasted pampas..."

"I wonder if you have ever read Evelyn Waugh's THE LOVED ONE, a devastating satire on the burial customs of Hollywood. It would amuse you, I think. Its the most macabre thing I've ever read –I can't believe its a true picture of what actually goes on, yet it seems to be: life of the mortician in Hollywood– Its certainly the best thing of its kind since Brave New World, and unlike most of his work it doesn't play down to anyone, the English gentry or the Catholics or anyone. In its curious way I think its a masterpiece –the first since Vile Bodies."

Art as one means of determining how places looked in the distant past.

Artistry: Thomas Girtin's seascape The White House at Chelsea, [Water color on paper] 1800.

The site where the estuary of the Thames River is today embanked.

Tate Gallery, London. Inspired many other artists of this period despite his death less than three years after this.

"Somewhere between Calabria and Corfu the blue really begins. You feel the horizon really beginning to stain at the rim, the sky needs to come a little nearer and into deeper focus, the sea darkens as it uncurls in troughs around the boat. You are aware not so much of a landscape coming to meet you invisibly over those blue miles of water, as of a climate.

Entering Greece is like entering a dark crystal; the form of things becomes irregular, refracted. Mirages suddenly swallow islands and if you watch you can see the trembling curtain of the atmosphere.

"Corfu is all Venetian green and spoiled by the sun.

Everywhere you go you can lie down on grass. Even the rocky northern end is rich in mineral springs: even the bare rock here is fruitful of water."

p. 187.

Corcyra... recalled on a passage to Crete....

"I remembered it all with a regret so deep that it did not stir the emotions; seen through the transforming lens of memory the past seemed so enchanted that any regret would have been unworthy of it."

p. 189.

"Time has done its stuff, the house is in ruins,... smashed. I think only the shrine with the three cypresses and the tiny rock pool where we had bathed is still left. How can these few hastily written words ever recreate more than a fraction of it."

p. 190.

(1949)

Olive orchards shaped the landscape & culture of southern Spain.

![]()

Desert drift

That which distinguishes any place from all others, is more obvious in a desert than perhaps anywhere else except volcanic islands such as the Galapagos or Hawaii where the land conspires --as it were-- to inhibit all but the most hardy plants and animals to thrive. On deserts as on newly extruded volcanic magma one can see landscape emerging at first as an inorganic stage where organic sorcery may begin to alter --actively sculpt-- or modify the underlying rock and water that cover other less harsh or extreme places.

magma one can see landscape emerging at first as an inorganic stage where organic sorcery may begin to alter --actively sculpt-- or modify the underlying rock and water that cover other less harsh or extreme places.

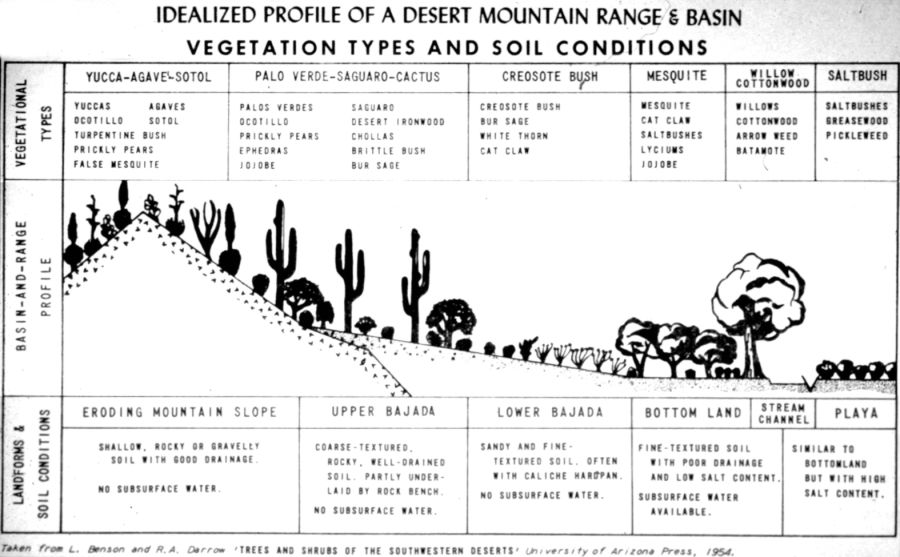

The play of these inorganic materials and the organic features of existence that so charmed Darwin and other naturalists of the past are clearly visible in the desert where plants adapt to warm, sun filled days and often chilly nights where the lack of moisture in any desert is even palpable to human skin, lips and mouth. Unlike mountain alpine regions that stay frozen or thaw but rarely, the desert encounters the extremes heat and cold testing if a plant can retain moisture, capture nutrients to enable it to take up carbon dioxide and water, all the while repairing itself, reproducing and adjusting to disturbance.

If anything a place is distinguishable by how its inhabitants have and will continue to adjust to disturbance and retain the vitality necessary to thrive amidst climate conditions that alter the vegetation over time, or respond vigorously to the predatory pressure that other animals, fungus or bacteria daily inflict. Places are just that --areas where the coping mechanisms, like thrifty water use in a desert-- ultimately define the association of living things. Naturalists in the 19th century clearly recognized that forests and savannah woodlands differed markedly in their associated plants and animals from grasslands,  deserts and polar tundra. These then are the garments of vegetation worn by the land, more easily spied out in deserts than in rainforests or woodlands.

deserts and polar tundra. These then are the garments of vegetation worn by the land, more easily spied out in deserts than in rainforests or woodlands.

Rene Dubos, the late human ecologist, suggested that there were, based on the ancient beliefs in genii loci, spirits that rested in places. These non-material manifestations of places are embodied in folklore by the dryades of the oak forests, the nymphs of woodlands, the faerie of flower beds, the divas of jungles, or the nereids of the seashores. Every folk story about landscape involve either horrible (such as griffins or centaurs) or benign (such as elves or witches) creatures who served as guardians over certain areas. In Chinese tradition dragons where associated with mountain ranges such as the Kun Lun Shan due to their imposing presences in the landscape.

Hecate was the deity, in Asia Minor, of the places where two roads merged or emerged, depending on one's direction. So places are distinguishable by natural vegetative elements that dictate the animals present and the culturally associated daemons -- all inhabiting, residing and contributing to the character of places because they each and all sustain the areas we seek to describe. In the desert there are deities as well and tangible materials that make the places distinct to our senses, our imaginations and our sciences.

But in the desert, bare of the traditional vegetative cover, we can see the rocks, beds of twisted layers in that rock, boulders and sands weathered from that bedrock in a way that nowhere else reveals the age, the great antiquity and the stamina of the earth's crust in spite of challenges from solar radiation, blasting winds, shifting weather and a near absence of water.

Hidden from view though underground water may be, the vegetation will always reveal where, if any, subterranean springs may lurk. And thus the lesson of places is that they are all different depending on their actual layers of accumulated rock and what we can see, imagine and find there. And the lesson of the desert is that we often do not know what we have, do not truly appreciate existence, until it is gone.

J. Siry

Desert Hot Springs, California

1-4-07

Terry T. Williams | D. H. Lawrence | Arnold Pacey | Tim Radford | Norris Hundley | Mary Austin | John Wesley Powell | Wallace Stegner | Siry, Marshes