Latin Identity

Latin Identity

What is the character of Latin-ness in Latin America?

Spanish heritage in the transformation of the America's

Spanish heritage in the transformation of the America's

No other part of the world, except perhaps the East Indies as it trails off into Melanesia, reveals so varied and diverse a set of cultural and social conditions as exists in the Caribbean and Central America. As such these are contested grounds where two very different clashes between reason and rectitude have persisted for over five hundred years. Added to the twin conflicts is a layering of influences both indigenous and introduced that has made it less clear as to the character, origins and importance of the Antillean, Caribbean, and Meso American nations.

The first conflict involves ethnic identity, the second economic importance, and the third is intellectual. In reversed order there is a difficulty associated with naming these places and their inhabitants. Besides a confusion about the name of the region that lies north of the equator and along the western shores of the Atlantic Ocean, there is an ideological debate about the roles of its historical characteristics and the economic development in the region. Added to these differences in points of view and persisting at a deeper intellectual level, there lurks a philosophical tension over what we know and how we express what critics have argued is a biased viewpoint bifocally nourished by patriarchy on one side and "cultural imperialism" on the other.

- Medieval legacy of the Islamic, Moors, unification and the reconquista.

- Aristotle's worldview, categories of experience; essentialist thinking, type.

- Roman Catholicism, the hierarchy of conservative faith on a monastic frontier.

- Arabic invasions: coffee, clocks, alcohol, horses, arches & aqueducts, the scientific learning of Asia with Roman and Greek ideas.

- France, the Bourbon dynastic claims and Napoleon's subjugation.

- Hapsburgs: Austria-Hungary, the Hapsburg dynastic claims and conservatism.

- Mongol invasions, pressed the Visigoths and Ostrogoths west.

- Russia, & Austria as examples of conservative empires (1814) comprised of many diverse nationalities.

- Renaissance, the belief in an identifiable humane quality & honor for human life.

- Geography the science of mapping the world to divide it up.

- Learning, classical education and Aristotelian logic.

- Architecture & art the neoclassical revival, baroque and rediscovering Vitruvius.

- Mathematics, Euclidean geometry, Arabic/Hindu numerals.

- Economy, mercantilism and "laissez faire" the big role of the metropolis.

History constrains us in each, but especially these steps:

1: What do we call the region?

2: How is identity important?

3: What is the economic condition of these geographical pieces of the Panamerican puzzle:

- Atlantic Islands and archipelagos

- European nation-states

- Spanish Main, or South American mainland

- Mayan Empires

- Aztec Empire

- North American

- borderlands

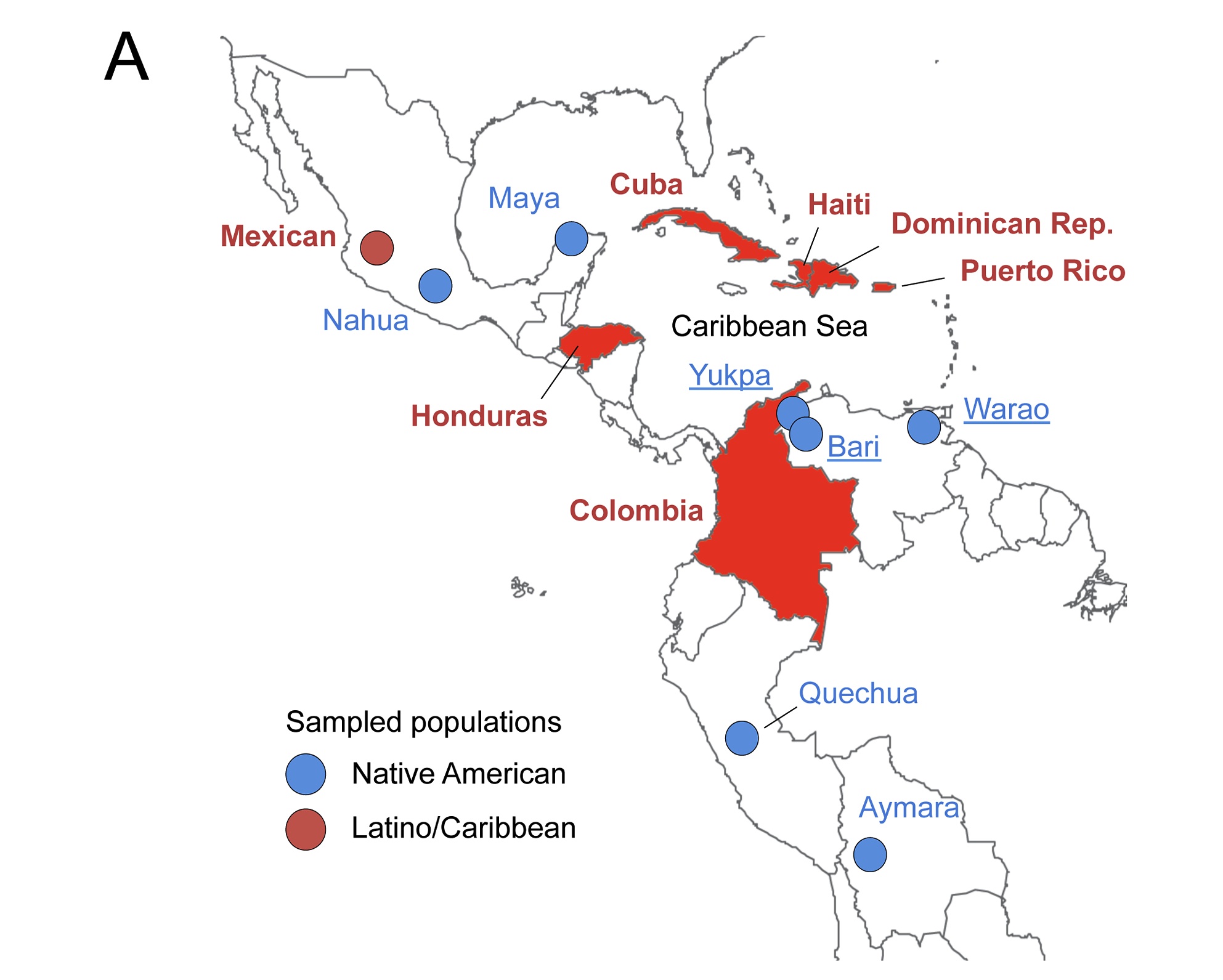

Latin is defined as speakers of ancient Latin based languages but primarily the Ibero-American, that is Portuguese and Spanish speaking, peoples and their dominant cultural areas in Asia and the Americas. The term "Latin America" was preferred by the French who invaded Mexico under Napoleon III in the 1860s in an attempt to have the region identify with European nations other than Spain. Yet there remain significant native speaking populations in Mexico, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia.

Ethnocentric qualities

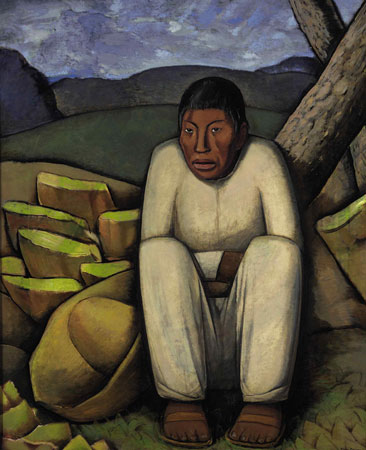

"The 'majority' is defined as 'Indian-Spanish', mestizo, or ladino, a term used for mestizos in Southern Mexico and Guatemala. But what exactly do these categories mean? How do we tell who an 'Indian' is?"

Identity issue Peoples of mixed ethnic heritage, mistakenly termed "races", are examples of multiple ethnicity. They represent also an important social movement called the Mestizaje process. This anthropological phrase was once thought of as a positive descriptive term for a progressive, even an organic, force in creating any nationality. The term as an adequate description of a people's ethnic identity and social conditions has come under some criticism by contemporary sociologists such as Mónica G. Moreno Figueroa.

"Rethinking Mestizaje: Ideology and Lived Experience"

PETER WADE

Department of Social Anthropology, University of Manchester

Abstract

The ideology of mestizaje (mixture) in Latin America has frequently been seen as involving a process of national homogenisation and of hiding a reality of racist exclusion behind a mask of inclusiveness. This view is challenged here through the argument that mestizaje inherently implies a permanent dimension of national differentiation and that, while exclusion undoubtedly exists in practice, inclusion is more than simply a mask. Case studies drawn from Colombian popular music, Venezuelan popular religion and Brazilian popular Christianity are used to illustrate these arguments, wherein inclusion is understood as a process linked to embodied identities and kinship relations. In a coda, approaches to hybridity that highlight its potential for destabilising essentialisms are analysed.

A counter view

"But it is an ideology which has been perpetuated in what was theoretically a liberal democratic post-colonial society in which all citizens are theoretically equal under the law. This is because the concept of mestizaje is not just a racial ideology. It was taken over and used in the attempt to construct a political ideology of modern national identity and unity, a nationalist ideology of social progress, by a state which claimed to be revolutionary."

"Although Mexico is formally a democracy, and has been ruled by civilians since the revolution, a single party has remained in power throughout the last 70 years. Far from delivering social justice to the Indians, the Mexican state has failed them utterly. Since 1994, its disastrous neoliberal economic policies have created mass unemployment and impoverished large sectors of the population, a situation which is producing a rapid unravelling of the regime and a mounting tide of violence in both town and countryside. The problem facing the indigenous rights campaigners in Mexico is how they win the support of broad sections of the public in a country in which Indians are seen as a "minority". One approach has been to try to deconstruct the established ideas about mestizaje: in other words, to invite ordinary Mexicans to reevaluate the "Indian" side of their identities as mestizos. "

"This brings us back to the problem of mestizaje. The government has made great efforts to foster a non-Indian "backlash" against demands for indigenous rights. This backlash effect is premised on the idea that most Mexicans are not Indians and that it is unjust to give some poor people special benefits because they can claim that they are indigenous. If Mexico is to become a multi-cultural nation in which Indians can assert their cultural traditions without being discriminated against, then the old idea of "whitening as progress" must be abandoned. But it is equally important that ethnic divisions are not seen as absolute and that people can feel community with people in other groups. Ethnic separatism and the idea that people are intrinsically different because of their culture are possible outcomes of a struggle for indigenous rights. What is needed to secure social justice is the idea that people have something in common beyond their differences and that all have an equal dignity in society and the nation. The politically-constructed category of mestizaje must lose its centrality to ordinary people's notions of their identity as Mexicans before that can happen."

Designed by John Gledhill.

For the Manchester University Department of Social Anthropology and the ERA Consortium.

Revised: March 29, 1998 .

Economic prejudice -

"The inequities of the area's income distribution remain staggering."

Political prejudice - immature democracies, power of persistent oligarchies.

Religious prejudice - authoritarian Catholicism versus "liberation theology"Humiliation of

• Conquest

• Slavery

Dependency Theory

"The economy of certain countries is conditioned by the development and expansion of another dominant economy."

|

"periphery" |

| Core | |

| "periphery" |

Dependency theory is the notion that resources flow from a "periphery" of poor and underdeveloped states to a "core" of wealthy states, enriching very few at the expense of the many and defended by a theory of trickle-down" commercial stimulus that eventually rewards the earnest and diligent.

Some may see that there is a parallel between dependency theory and reform Christianity. Others may argue that dependency theory is a secular spin-off of the Protestant ethic stripped of its spiritual rewards. Instead of a transcendent system of reward and punishment materialism is substituted and with that substitution comes monetary wealth and poverty. Excess money is the new heaven on earth and unsustainable impoverishment – if not starvation– the equivalent of perdition in hell.

A progression in the "dominant economy" category:

- Europe 1492-1917

- Spain, sixteenth & seventeenth centuries

- France, eighteenth century

- United Kingdom,

nineteenth century

- USA 1917 - 1980

- Globalization 1980s - now

|

Keen and Haynes, Imperialism's origins and extent |

William E. Burghardt DuBois, The Negro,

|

|

| Octavio Paz , The Labyrinth of Solitude |

The fascination of urban Europe and later north America with the exotic peoples of the earth has been fed, no less by the Caribbean isles and the South American mainland, than by Asian and African remoteness. Latin America holds for us both a deep fascination and an appalling horror. Indeed the "Spanish Main" is actually the intrepid product "Spanish manifest destiny" that has clashed historically with the United State's eagerness to possess the continent's vast resources time and again from Florida (1820s) to Texas (1840s) and California, to Cuba (1850s) and ultimately the entire Caribbean (1896).

In this long rivalry of Anglo-Iberian origins but emerging in the United States or British rebel colonies from 1783 until today, the blindness of the United States [US] to the true conditions of the Americas has hampered the furtherance of US interests in the West Indies, Mexico and South America.

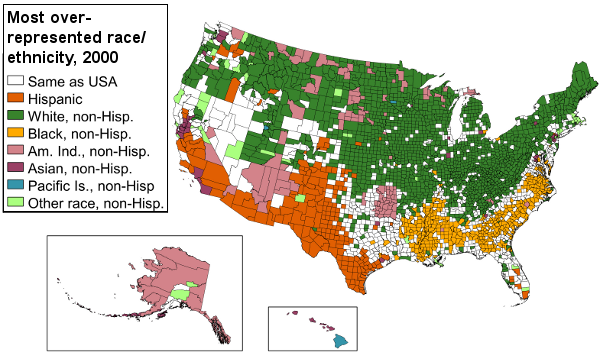

Far from the siblings of democracy and the enlightenment that the America's are, an inherent xenophobia in the United States has caused us to assume a mistaken superiority with respect to Latin American peoples. In our failure to look beneath the "Latin-ness" we miss the multiracial character and diverse conditions of the dominant indigenous, Afro-American and minority communities that together comprise the Americas. The cruelty with which the Caribbean was settled, occupied, subdued and controlled in some ways lingers, despite, the yearning of its peoples very early on for democratic and egalitarian values. Blind to the ancient origins of ideas and expressions of order that emerged in Mexico, the Caribbean and Latin America, in part because of our national aversion to Iberian culture, sophisticated learners in the United States need to see these "Spanish borderlands" with new frames and fundamentally "unblinkered" eyes.

J. Siry (2008 & 2014)

Date: 19 March 2008, Sunday, 16 November, 2014 6:57 PM

.gif)