Bull Dozer's a coming

Bull Dozer's a coming  Part II

Part II What interfered with the spread of solar power in American suburbs and what did that failure to thrive eventually lead to? (answer)

Clearwater city and beach on Boca Ciega Bay, Fla. photo JVS, 2003

"AT the federal level, the effort to develop solar technology was handicapped further by a change in the political climate after the election of Dwight Eisenhower. The Republicans (party) had much more faith in the cornucopian promise of the free market. At the opening session of a 1953 conference sponsored by Resources for the Future. . .the new president warned the participants about the danger of heading the calls of 'extremists.' The federal funding for solar research soon went from a drop to a speck."

p. 54.

"We have always lived in a suburban area, but until we built our solar house, I really didn't appreciate the stimulation of being able to observe the day-to-gay routine of life that fairly teems all around us."

Suburban homemaker, (p. 56)

" a house that is cheaper to run."

p. 57.

"Habits of thrift began to seem old-fashioned."

p. 63.

"The new techniques of mass-building also increased the amount of energy needed to heat and cool homes. To speed the work of site preparation, the typical subdivision builder cleared away every tree in the tract, so millions of post war homes had no shelter against the bitter winter winds and brutal summer sun."

p. 61.

"By 1950, however, the regional traditions of design were in decline. The rise of the balloon-frame form of construction, the mail order house, and the mass produced subdivision all had led to a more uniform architecture."

This older approach–show above–based on colonial mortise & tenon construction was replaced by balloon framing.

The percentage of multistory homes also fell, as builders sought to save time and money by avoiding staircase construction –and to satisfy a new demand for the one story ranch or rambler.

Again, the result was to result was to increase the use of energy for heating and cooling, since a one-story house has more exposed surface area per square foot than a one-and-a-half or two-story house."

Again, the result was to result was to increase the use of energy for heating and cooling, since a one-story house has more exposed surface area per square foot than a one-and-a-half or two-story house."

pp. 61-62.

"To complete the argument, homebuilders stressed the economic and social value of air conditioning. The new technology would prove a sound investment. Because push-button climate was the wave of the future, a home without built-in cooling would soon be outdated."

p. 69.

The 1945 to 2005 boom in suburban housing was accompanied by cars, the National Defense Highway Act of 1956, and septic tank systems that did not require extensions of urban sewer and storm drain lines; and were thus cheaper than urban dwellings.

p. 87.

Charles Abrams, 1946:

"The challenge to the postwar democracy–whether it can employ its people and distribute its goods and services more equitably–cannot be met without a solution of the housing problem."

The rise in air conditioning and central heating in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

pp. 65-83.

Efficiency

"Many builders followed Carrier's [air conditioning company] suggestions, In 1959, for example, the largest builder in Florida abandoned the sleeping porch. 'I figured that for the cost of a Florida room I could air condition the whole house."

pp. 71-72.

These all-electric homes were so popular and they fostered kick-backs to the builders of from $500-$900 per home from the appliance manufacturers.

pp. 78-79.

FHA lowered its insurance standards twice in the 1950s reducing insulation

"The Cadillac of homes at a Pontiac price"

That is to say a luxury level house at bargain prices.

pp. 76-83.

Do compare your home to the post-war model home.

Energy

"they also wanted a host of high-energy comforts and conveniences."

"The relative inefficiency of electric heat was even greater in the early 1950s, as a number of analysts noted at the time. The President's Materials Policy Commission even advised against the use of electricity for home heating. 'Electricity is of course the ideal fuel, in that it is easier to control than any other, and is more convenient,' the commission concluded in 1952. 'It is inherently a very wasteful form of heat, however, and from the viewpoint of social benefit and economy, should be used only for power purposes.' But the recommendation went unheeded: The wastefulness of electric heat did not become a subject of public controversy until a generation later. In the 1950s and 1960s, the nation still seemed to have energy to burn."

Electrical power plant situated, as this coal unit photographed above is like other oil or nuclear fueled facilities in that they all must be beside sufficient sources of water for steam and for cooling.

"the growing reliance on electric heating also contributed to a sharp rise in the total residential demand for electricity: from 1950 to 1970, the increase was almost 400 percent."

p. 81.

"a further consequence of expanding suburbanization was fueled by public utility regulation based on providing electrical transmission of power at the least cost per kilowatt hour to the consumer. The fuels of choice for such a policy were coal and oil in the 1960s because they were cheaper than rival fuels such as natural gas even though that is a more efficiently burning source of heat and power."

J. Siry, 1995.

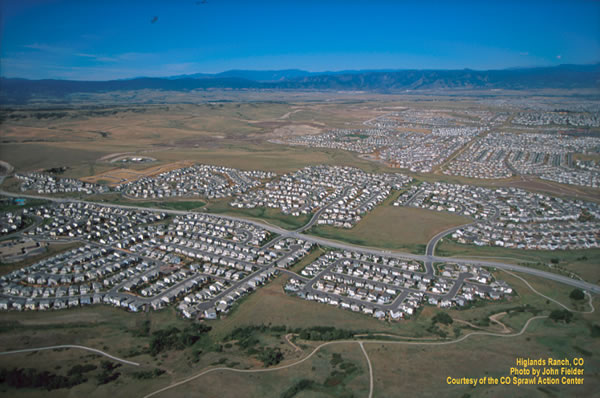

Denver, the wild west in a backyard dude ranch.

Since 1981, 70,000 people have moved into Highlands Ranch, and about 9 more move into newly built houses there every day. It may be America's largest subdivision, depending on how you define the term. There's one in Irvine, California that may soon be larger. These ranches -- which aren't really ranches, but millennial versions of suburban subdivisions -- are evidence of a larger trend. Sometime last year, Americans crossed a milestone: Now slightly more than half of all U.S. residents live in the suburbs. The rate at which Americans are embracing this version of the suburban lifestyle means that every major American city could have its own version of Highlands Ranch within 25 years.

Source: FastCompany: Issue 48 | June 2001 | Page 124 | By: Ron Lieber.

"But the transition from wartime concern about scarcity to post-war abundance cannot explain some of the most important heating-and-cooling decisions of the 1950s and 1960s. The story of air conditioning makes that clear. The ever-increasing amount of energy used for cooling was partly a sign that Americans could afford a higher level of comfort, but the air conditioning load was also a consequence of decisions builders made in order to hold down the cost of construction: To install air conditioning on a budget, builders eliminated traditional ways of providing for shade and ventilation.

The success of electric heat similarly was not a simple function of affluence . . . because the alternatives were less profitable."

p. 85.

Book

"The constraints on consumer choice also help to explain the environmental flaws of tract housing. In a survey of homeowners conducted in the early 1950s, a significant number said they would have preferred a more efficiently heated and ventilated house, but that preference was not a priority."

"The postwar decades thus suggest the weakness of consumer driven environmentalism. . . .the nation's consumers were either unwilling or unable to conserve energy."

"The result in each case was a dramatic increase in energy consumption."

p. 86.

Phoenix, Arizona is a city built on cheap federally subsidized water and highways with all electric homes.

"A 1958 study found that more that more than 70 percent of subdivision homes had septic tanks."

p. 88.

Essay

The Bulldozer in the Countryside explicitly connects once isolated parts of the landscape into a revealing prism refracting the whole problem of our patterns of consumptive use. These once isolated parts of conservation from forestry preservation to wildlife protection also includes energy and water use. He ties energy and water use to both air and water pollution. When these are linked to the loss of open space, a rejection of conservation as practiced before the war emerged and propelled the adoption of an eco-centric ethic that spawned 'environmentalism'.

Rome argues that "A profound turning point in American environmental history" occurred in the transition from the climate-conscious, energy-efficient home of the 1940s and the electricity intensive home of the 1960s. With that shift in consumer preferences and developer constraints grew both the environmental protection and the property rights counter movements rival siblings in a nest they soon both outgrew; the suburban backyard.

At one point, Highlands Ranch really was a working cattle ranch.

For much of the middle of the past century, the land was owned by the family of former U.S. senator Lawrence Phipps. Oil tycoon turned movie baron Marvin Davis led a partnership that bought the land in 1978 and that then flipped it to the Mission Viejo Company, developer of much of the California city of the same name.

Mission Viejo, then a subsidiary of Philip Morris, pressed on, and in 1981, the first family moved into the community. Interest rates at the time were so high that builders had to subsidize mortgages for most of the buyers. Nevertheless, a persistent trickle of families moved in, and the numbers increased every year. Growth slowed toward the end of the 1980s -- but never stopped.

Size, matters even more in real estate:

"By 2005, when the Ranch is completely built, there will be 90,000 people living in 36,700 homes spread across 34.4 square miles. A full 61% of the acreage will be reserved for open or non urban space, off-limits to any sort of commercial or residential development. Eventually, much of it will become a nature preserve."

Source: FastCompany: Issue 48 | June 2001 | Page 124 | By: Ron Lieber.

The bulldozer serves as symbol of the explosive growth of suburbia in the decades following World War II but simultaneously shatters the domestic tranquility as it moves ever so noisily through our countryside performing the ultimate high-end, make-over.

"The success of electric heat was not a simple function of affluence. In most cases the decision to install electric heat was made by builders, not homebuyers, and builders often chose electric heat because the alternatives were less profitable."

p. 85.

"The argument for development remained powerful."

p. 118.

![]()

American conservation movement.

Aldo Leopold and a re-envisioning of the landscape.

Ian McHarg and the reaction against sprawl .

Ecological Design is "smart building".

Merchant's Chronology 1640-1992

J. Siry

26 November 2007 | 2015