Essay

Edge of time

Essay

Edge of time

Sample essays on Rachel Carson's themes:

At the edge of the sea we stand too at the edge of time and come face to face with our own inabilities to understand the basic necessity for an essential, delicate balance among preservation, conservation & development if we and the coastal edge are to coexist.

“The shore is an ancient world, for as long as there has been an earth and sea there has been this place of the meeting of land and water.”Rachel Carson, The Edge of the Sea, p. 2.

"A rising sea would write a different history."

Edge, p. 246.

Thesis | essay | overview | book's contents | Ecological problem's three components | sense of her text

The sea's edge is a prism through which we may discover, hidden in its depths, clues to who we are and how we may live.

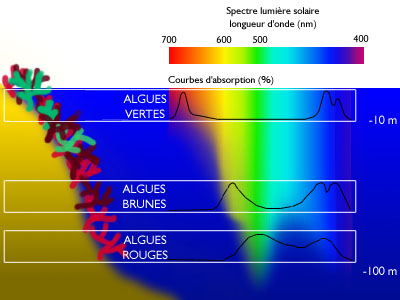

visible light is absorbed at depth in different bands or wavelengths

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Surface | wavelengths | Photic zone |

red |

by 1 m about 60% of the light is absorbed. | |

| amber | by 10 m about 85% of the light has been absorbed. | |

| yellow | ||

| green | 50 m | |

| blue | 100 m | |

| Depths | by 150 m about 99% of light has been absorbed. | |

One meter or 1m is equal to just more than three feet, 1 : 3

The land's margins "becoming fluid as the sea itself."

The ocean shoreline is not just the land's margin, and not exactly a borderland in space; instead we stand at the edge of time and beside these spaces where water shatters light into its constituent parts. Thus as Rachel Carson suggests at the seashore we "gain some new awareness of its beauty and its deeper meanings." * This staging ground for natural wonders simply displayed, hides the complexity of the species found there because each creature displays in its life cycles, migration and reproduction the hidden lessons of productivity, biodiversity, endurance, and adaptation that are "the intricate fabric of life." **

Along the sea’s margins Carson has discovered "where the drama of life played its first scene on earth," and "where the forces of evolution are at work today as they have been since the appearance of what we know as life."*** It is in her words about life along the littoral that the movement of water is but a metaphor for time's passing and the movement of life through geologically ancient seas, carrying our very inheritance as mere strewn debris along the this "shoal of time."

In her writing Carson manages to fill these ocean shores --rocky shores, beaches, or coral coasts-- with plants, animals, forces and events so well that anyone may discover "where the riddle is hidden" that reveals how productivity, predation, diversity, and reproduction of life in our "world is crystal clear."***

In even her opening discussion of the ghost crab she says that "for the first time I knew the creature in its own world." Here she discovered "the little crab alone alone with the sea became a symbol that stood for life itself," despite the "harsh realities of the inorganic world." (p. 5) Here it is revealed in miniature that the riddle involves the place where the inorganic pulls away from the organic life of the planet in a constant exchange where one is not understood fully without its relationship to the other. Here in the crash of a wave crest along the edge of time one may see in stark relief both the spectrum of light that embeds the rainbow in our memory and presents a hidden spectrum of life that accounts for the very bacteria in our gut and the very oxygen in our lungs.

Not quite evident to our sense of sight and sound is the five kingdoms of life that cooperate in a sort of endless exchange of nutrients, energy, and trace elements. The lesson hidden here is that two opposite things together -- living and nonliving-- are never far apart. In all the diversity of life, Carson finds " by the very fact of its existence, that it has dealt successfully with the realities of its world." (p.11) She insists that "the shore, with its difficult and changing conditions, has been a testing ground in which the precise and perfect adaptation to environment is an indispensable condition of survival." (ibid) It is this testing ground of zones and habitation that --in microcosm-- reveal the forces that enable an entire world to function. And thus the riddle of life begins to attract our attention: " The patterns of life," she insists are "created and shaped by these realities," such that Carson hints "that the major design is exceedingly complex." because those very "realities intermingle and overlap."

Just as the tidal movement along the shore carves out features and generates overlapping zones, each creature she looks at more closely reveals the overlapping of one organisms needs and functions on the others in its immediate or far strung communities. Life appears woven into the seascape whether it is found among the muds of the mangrove shores, the grass beds of bays, the sand beaches of the high energy coast, or the rock bound promontories, by cycles of growth, predation, reproduction and renewal.

Of the numberless plants and animals that Carson describes, there are six or seven that she examines in their relation to their surroundings and to one another, that allow one to understand Carson's underlying recognition of the coastline's enduring value as the place where creatures adjust to survive such as when "turtles emerge from the ocean and lumber over the sand like prehistoric beasts to dig their nests and bury their eggs." (p. 237) These organisms in their own manner provide assurances to human society of the tenacity of life along the otherwise inhospitable conditions of competition and adaptation at the sea's edges.

Barnacles reveal the adjustment of crustaceans to water and cycles of reproduction attuned to the new and full moons.

"Barnacles are perhaps the best example of successful inhabitants of the surf zone, limpets do almost as well."

(p. 15-16, 51-55, 120-121.)

The reason these barnacles survive on the outer shores are that they secrete a "natural cement of extraordinary strength" and as Carson points out the body plan is one that possesses a "low conical shape" that "deflects water."

Limpets, too reveal the roles of zones, of the place of grazers in relation to other creatures in the food chain, the homing instincts of animals, and the adjustment of snails to stress. "It lives entirely on the minute algae that coat the rocks with a slippery film, or on the cortical cells of larger algae."So effective is their radula or raspy feeding appendage that Carson writes, "they keep the rocks scraped fairly clean." (60-61). The gametes or eggs of the limpet float in the sea and are fertilized there by sperm. Later the immature limpet larvae settle out on the rocks and mature.

(p. 58-61.)

Pisaster as the Pacific star fish or Oreaster as the Atlantic giant star are examples of predation and reproduction in the intertidal zone revealing the cycle of its life is tied to the changes in the seas. "These moss meadows "seem to be one of the chief nurseries of for the starfish," she notes tying the rocky intertidal moss zone to the success of these predators. She explains how the larval forms of star fish undergo a metamorphosis of body form from the juvenile into the adult stage when they settle down on the rocks of the sub-littoral zone.

p. 97-98.

Limulus or "the horseshoe crab," she suggests "is an example of an animal that is very tolerant of temperature change." Limulus she notes "has a wide range as a species, and its northern forms can survive being frozen into ice, . . . while its southern representatives thrive in tropical waters of Florida . . .to Yucatan."

(p. 19, 133, 147)

Sea squirts or marine ascidians (p. 269-270) are "the most common representatives on the shore" of the forerunner of chordates. These filter feeders and radially symmetrical creatures that are a reminder of speciation and our ancestry as it emerged fro the radially symmetrical marine ascidians and this is revealed in their larval stage, wherein the creature is bilaterally symmetrical. As such this is the evolutionary signal of how through neotony, nature in many cases has through selection generated new forms of life.

pp. 175, 269-270.

Lingula or lamp shells are marine invertebrates today viewed as disputed but nonetheless remnant member resembling populations of creatures found in Silurian and Ordovician rocks and descended from an ancient form of brachiopod.

Corals are the master builders of the ocean's edge where productivity, diversity and ecological stability or optimality can all be better understood as a biogenic process wherein life changes the conditions of its existence to the extent that it can also create an exposed habitat along the shore.

Coral reefs can and have changed the planet's oceans as they thrive in warm tropical seas of great clarity and build enormous walls of chalk or calcium carbonate rock.

(pp. 198-206.)

The Kelp Forest "like the animal life of this coast, the seaweeds tell a silent story of heavy surf," she insists,"one of these laminarian holdfasts is something like the roots of a forest tree, branching out, . . . in its very complexity a measure of the great seas that roar over the plant."

(pp. 61, 65.)

Sea grasses are actually the flowering plants of these shores, whereas the kelps are members of the algae related species that occupy coastal waters transforming light in to the food that other creatures feed upon.

As Carson notes "But the seed plants originated on land only within the past 60 million years or so and those now living in the sea are descended from ancestors who returned." (230) And as all angiosperms, she explains that "They open their flowers under the water; their pollen is water-borne; their seeds mature and fall and are carried away by the tide." Once the seeds settle out in quiet waters "they help secure the offshore sands against the currents, as on land the dune grasses hold the dry sands against the wind." For in their tenacity and adaptation to the sea, these sea grasses create a habitat for life."In the islands of turtle grass many animals find food and shelter." such as Oreaster or giant starfishes, the Queen Conchs, tulip shells, octopuses and sea horses.

(pp. 230-231.)

One member of the kelp forest community is Enhydra lutris lutris or the Pacific Sea Otter. This creature was once a land dwelling carnivora and as it has returned to the sea, its behavior at once, reveals the ecological importance of keystone species, the edge effect, and predation --but in the larger context these social animals indicate the importance too of marine mammal protection for the life and health of the seas and our coasts because they were nearly hunted to extinction for the its fur.

The "edge effect" is an example of the anomalous character of the shore. Where land and water intimately intermingle we expect the unexpected. Some organisms called barnacles plant their heads down cemented to the rock and throw their legs in the air, among the rocks where waves crash. Barnacles, mussels, or bryozoans are but one example of how the unexpected life form thrives in areas where we might otherwise expect life to be sparse, because of the stress of the salt water, the tides and the pressure of the crushing waves.

The edge effect implies that creatures from the land, such as the sea otters that depend on marine snails and crustaceans, or Galapagos iguanas, mingle, even depend on marine algae, along the seashore. Normally a land creature, marine iguanas of the Galapagos Islands take to the sea to survive and even thrive. The edge effect generally occurs wherever an overlap between one ecological community and an adjacent neighboring community exists; the overlap produces a greater array of creatures inhabiting these edges, than either of the adjoining communities.

"Beneath the surface beauty there is a marvelous complexity of structure and function." Carson writes of the sea tunicate Botryllus, a "highly organized" colonial creature. (pp. 67-68) But she could just as easily be saying this of the creatures we have discussed as indicator species, revealing the actual "depth" and span of the sea's edge as a harbor of diversity and a haven for productivity in an otherwise and often barren world. Here too at the sea's edge we can view a prism through which we discover, hidden in its depths, clues to where we orginated, how we got here, and how we may better live.

1800 words

- The Edge of the Sea, page 2.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, page 7.

- .Ibid, page 11.

- Amphipods, Amphithoe, pp. 92-93..

Sample food chain:

”Phytoplankton"

Blue Green bacteria or cyanobacteria

Diatoms, see Cal Academy of the Sciences. These are BACILLARIOPHYTA or Diatoms being unicells that share the feature of having a cell wall made of silicon dioxide. This opaline or glass walls are composed of two parts (valves), which fit together with the help of a cingulum or set of girdle bands.The taxonomy of diatoms is based in large part on the shape and structure of the siliceous valves.

Dinoflagellates are members of the Phylum Dinoflagellata is in the Kingdom Alvoelata, part of the former Kingdom Protista, now broken up into many kingdoms. Dinoflagellates are characterized by their flagella located in grooves in cellulose plates surrounding the cell. They also have membrane bound sacs known as alveoli in the plasma membrane. It is unclear what the function of these alveoli are, but perhaps they help stabilize the surface of the cell, as well as regulate water and ion content.

A component of phytoplankton, dinoflagellates are found mostly at water surfaces. They contain chlorophyll a and c, as well as other carotenoid and xanthophyll pigments.

When dinoflagellates bloom, or explode in population size, they actually change the water to a reddish brown color due to these pigments. This phenomenon causes red tides, which can have a deadly affect to both marine animals and humans. Recently, the outbreak of red tide has increased, and one possible reason may be water pollution with fertilizers, which contain nitrates and phosphates that the dinoflagellates take up.

All of the above creatures possess chloroplasts. Chloroplasts are specialized organelles found in all higher plant cells. These organelles contain the plant cell's chlorophyll, hence provide the green color. They have a double outer membrane. Within the stroma are other membrane structures - the thylakoids and grana (singular = granum) where photosynthesis takes place..

”Zooplankton"

Radiolarians are single-celled protistan marine organisms that distinguish themselves with their unique and intricately detailed glass-like exoskeletons. During their life cycle, radiolarians absorb silicon compounds from their aquatic environment and secrete well-defined geometric networks that comprise a skeleton commonly known as a test.

”Filter feeders"

Lingula (Zool.) Any one of numerous species of brachiopod shells belonging to the genus Lingula, or lamp shells, and related genera of marine invertebrates that are filter feeders. the Lingula family of brachiopod sea creatures is the oldest known family of multi-cellular creatures which has hardly changed throughout its time on this planet.

You can find fossils of this creature in rocks 550 million years old, where most of the other creatures are strange and weird, yet today you can find living specimens in the waters around Japan which are almost identical.

See Algae and protists.

The red, brown and yellow algae -- some sea kelps are structurally rather complex; some red algae have protected reproductive organs; some algae lack chlorophyll; and some are prokaryotes (lack nuclei), e.g. the cyanobacteria or blue-green algae.

To research a creature, see Earth life.

A testing ground of conservation & preservation.

All

ecological problems have three parts:

Physical components, Biological components. Social components.

- high density centers of biological diversity beside human populations.

- essential pathways for migratory mammals, turtles, fish, and birds.

- active margins where sand, mud, rock and water are in constant motion.

- original places for evolution?

- New opportunities for redefining conservation.

Contents of Carson's 1955 book.

overview of The Edge of the Sea.

- Concept, related ideas.

- Essay about conserving biological wealth.

- Trace elements can have more than trace effects!

- Protection of the global commons.

- Marshes of the Ocean Shore

Science Index | Site Analysis | Population Index | Global Warming Index | Nature Index